Thoracic duct

| Thoracic duct | |

|---|---|

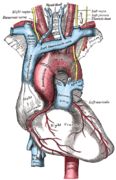

The thoracic and right lymphatic ducts. (Thoracic duct is thin vertical white line at center.) | |

Modes of origin of thoracic duct. (a) Thoracic duct. (a′) Cisterna chyli. (b), (c′) Efferent trunks from lateral aortic glands. (d) An efferent vessel which p...[clarification needed] | |

| Details | |

| System | Lymphatic system |

| Source | Cisterna chyli |

| Drains to | Junction of the left subclavian vein and left internal jugular vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | ductus thoracicus |

| MeSH | D013897 |

| TA98 | A12.4.01.007 |

| TA2 | 5137 |

| FMA | 5031 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In human anatomy, the thoracic duct (also known as the left lymphatic duct, alimentary duct, chyliferous duct, and Van Hoorne's canal) is the larger of the two lymph ducts of the lymphatic system (the other being the right lymphatic duct).[1] The thoracic duct usually begins from the upper aspect of the cisterna chyli, passing out of the abdomen through the aortic hiatus into first the posterior mediastinum and then the superior mediastinum, extending as high up as the root of the neck before descending to drain into the systemic (blood) circulation at the venous angle.

The thoracic duct carries chyle, a liquid containing both lymph and emulsified fats, rather than pure lymph. It also collects most of the lymph in the body other than from the right thorax, arm, head, and neck (which are drained by the right lymphatic duct).[1]

When the duct ruptures, the resulting flood of liquid into the pleural cavity is known as chylothorax.

Structure

[edit]In adults, the thoracic duct is typically 38–45 cm in length and has an average diameter of about 5 mm. The vessel usually commences at the level of the twelfth thoracic vertebra (T12) and extends to the root of the neck before descending to terminate at the venous angle.[2]

Origin

[edit]The thoracic duct commences at the upper extremity of the cisterna chyli[3] at the level of the T12 vertebra.[2]

Course and relations

[edit]Abdomen

From its origin at the cisterna chyli, the thoracic duct ascends anterior to and to the right of the vertebral column, situated in between the aorta, and the azygos vein.[3] The thoracic duct traverses the diaphragm at the aortic hiatus[3] to enter the posterior mediastinum.[3]

Posterior mediastinum

It ascends the posterior mediastinum between the descending thoracic aorta (to its left) and the azygos vein (to its right),[4] and is situated posterior to the esophagus at the T7 vertebral level. It crosses the midline to the left side at about the T5 level, continuing to ascend. It then passes posterior to the aorta, and to the left of the oesophagus.[3]

Superior mediastinum

The thoracic ducts ascends into the superior mediastinum, reaching 2-3cm superior to the clavicle,[3] as high up as the C7 vertebral level.[5]

In the superior mediastinum, the thoracic duct is situated posterior to and to the left of the esophagus. It is situated between the visceral and alar fascia.[5] It passes posterior to the left common carotid artery, vagus nerve (CN X), and internal jugular vein.[3] At C7 level, it lies posterolaterally to the carotid sheath. From here, it passes anteroinferiorly to the thyrocervical trunk, and phrenic nerve.[5] It descends until reaching and draining at the venous angle.[3]

Fate

[edit]The thoracic duct usually[3] drains into the systemic (blood) circulation at the left venous angle where left subclavian and left internal jugular veins unite to form the left brachiocephalic vein.[2][3]

Variation

[edit]The characteristic anatomy of the thoracic duct is present in only about half of individuals.[3]

Origin

A cisterna chyli is absent in about half of individuals; the cisterna chyli fails to develop when the fusion of lumbar trunk during embryologic development occurs above the vertebral level of T12. In such cases, dilation of the lumbar trunks may be present instead.[3]

Number of ducts

A bifid inferior portion of the thoracic duct (due to a failure of fusion during embryonic development) is not uncommonly observed; a plexus of lymphatic vessels replacing the thoracic duct inferiorly and only coalescing into a single duct in the mediastinum may also occur. Rarely, the thoracic duct may be entirely bilaterally paired.[3]

Termination

In over 95% of individuals, the thoracic duct ends by draining either at the venous angle, or into the internal jugular vein, or the subclavian vein, but - in the minority of cases - empties into either the brachiocephalic vein, external jugular vein, suprascapular vein, transverse cervical vein, or vertebral vein.[3]

In a vast majority of cases, the thoracic duct terminates on the left side, but may rarely terminate on the right side of the body, or bilaterally. It usually terminates as a single vessel, but it sometimes ends in bilateral vessels or as several terminal branches. Rarely, the thoracic duct terminates "prematurely" by emptying into the azygous system.[3]

Function

[edit]The thoracic duct collects most of the lymph in the body other than from the right thorax, arm, head, and neck.[6] These are drained by the right lymphatic duct.[1]

The lymph transport, in the thoracic duct, is mainly caused by the action of breathing, aided by the duct's smooth muscle and by internal valves which prevent the lymph from flowing back down again. There are also two valves at the junction of the duct with the left subclavian vein, to prevent the flow of venous blood into the duct. In adults, the thoracic duct transports up to 4 L of lymph per day.[7]

Clinical significance

[edit]The thoracic duct becomes adaptively dilated in the presence of certain pathological conditions (congestive heart failure, portal hypertension, and malignancy).[3]

The first sign of a malignancy, especially an intra-abdominal one, may be an enlarged Virchow's node, a lymph node in the left supraclavicular area, in the vicinity where the thoracic duct empties into the left brachiocephalic vein, right between where the left subclavian vein and left internal jugular join (i.e., the left Pirogoff angle). When the thoracic duct is blocked or damaged a large amount of lymph can quickly accumulate in the pleural cavity, this situation is called chylothorax.

Additional images

[edit]-

Transverse section of thorax, showing relations of pulmonary artery.

-

The arch of the aorta, and its branches.

-

Deep lymph nodes and vessels of the thorax and abdomen (diagrammatic).

-

The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum. Seen from behind.

-

Front photo of the ductus thoracicus in the human mediastinum with the heart and part of the pericard removed.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Schuenke, Michael; Schulte, Erik; Schumacher, Udo; Ross, Lawrence M.; Lamperti, Edward D.; Voll, Markus; Wesker, Karl (24 May 2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: Neck and internal organs. Thieme. pp. 136ff. ISBN 978-3-13-142111-1. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ a b c Ellis, Harold; Insull, Phillip (1 October 2007). "Clinical Anatomy: Applied anatomy for students and junior doctors". ANZ Journal of Surgery. 77 (10) (11th ed.): 911–912. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04191.x. ISSN 1445-2197. S2CID 70800205.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Ilahi, Maira; St Lucia, Kayla; Ilahi, Tahir B. (2022), "Anatomy, Thorax, Thoracic Duct", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 30020599, retrieved 30 December 2022

- ^ Schipper, Paul; Sukumar, Mithran; Mayberry, John C. (1 January 2008), Asensio, JUAN A.; Trunkey, DONALD D. (eds.), "Pertinent Surgical Anatomy of the Thorax and Mediastinum", Current Therapy of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care, Philadelphia: Mosby, pp. 227–251, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-04418-9.50037-0, ISBN 978-0-323-04418-9, retrieved 18 November 2020

- ^ a b c Quiñones-Hinojosa, Alfredo (2021). Schmidek and Sweet: Operative Neurosurgical Techniques 2-Volume Set (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsavier. p. 2076. ISBN 978-0-323-41519-4. OCLC 1253347770.

- ^ Jacob, S. (1 January 2008), Jacob, S. (ed.), "Chapter 3 - Thorax", Human Anatomy, Churchill Livingstone, pp. 51–70, doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-10373-5.50006-3, ISBN 978-0-443-10373-5, retrieved 18 November 2020

- ^ Tewfik, Ted L.; Mosenifar, Zab (7 December 2017). "Thoracic Duct Anatomy". Medscape. WebMD Health Professional Network.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy figure: 21:05-02 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center — "The thoracic duct and azygos venous network"

- Anatomy image:8901 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- figures/chapter_24/24-5.HTM: Basic Human Anatomy at Dartmouth Medical School

- "Ultrasound imaging the thoracic duct".

- "Instruction video for Ultrasound examination of the thoracic duct".