Columbia Records

| Columbia Records | |

|---|---|

Logo since 1999 | |

| Parent company |

|

| Founded | January 22, 1889 (as Columbia Phonograph Company) in Washington, D.C. |

| Founder | Edward D. Easton |

| Distributor(s) |

|

| Genre | Various |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Location | New York City |

| Official website | columbiarecords |

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the American division of multinational conglomerate Sony. Columbia is the oldest surviving brand name in the recorded sound business,[3][4][5] and the second major company to produce records.[6] From 1961 to 1991, its recordings were released outside North America under the name CBS Records to avoid confusion with EMI's Columbia Graphophone Company. Columbia is one of Sony Music's four flagship record labels: Epic Records, and former longtime rivals, RCA Records and Arista Records as the latter two were originally owned by BMG before its 2008 relaunch after Sony's acquisition alongside other BMG labels.[7]

History

[edit]Beginnings (1889–1929)

[edit]

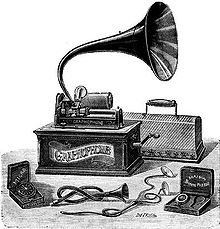

The Columbia Phonograph Company was founded on January 15, 1889, by stenographer, lawyer, and New Jersey native Edward D. Easton (1856–1915) and a group of investors. It derived its name from the District of Columbia, where it was headquartered.[9][10]

Columbia's ties to Edison were severed in 1894 with the North American Phonograph Company's breakup. Thereafter, it sold only records and phonographs of its own manufacture. In 1902, Columbia introduced the "XP" record, a molded brown wax record, to use up old stock. Columbia introduced black wax records in 1903. According to one source, they continued to mold brown waxes until 1904 with the highest number being 32601, "Heinie", which is a duet by Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan. The molded brown waxes may have been sold to Sears for distribution (possibly under Sears' Oxford trademark for Columbia products).[11]

In 1908, Columbia ceased the recording and manufacturing of wax cylinder records after arranging to issue celluloid cylinder records made by the Indestructible Record Company of Albany, New York, as "Columbia Indestructible Records". In July 1912, Columbia decided to concentrate exclusively on disc records and ended production of cylinder phonographs, although Indestructible cylinders continued to be sold under the Columbia label for a few more years. Columbia was split into two companies, one to make records and one to make players. Columbia Phonograph relocated to Bridgeport, Connecticut, and Edward Easton went with it. Eventually it was renamed the Dictaphone Corporation.[9]

Columbia Phonograph Company ownership (1925–1931)

[edit]

In late 1922, Columbia entered receivership.[12]

The company was bought by its UK subsidiary, the Columbia Graphophone Company, in 1925 and the label, record numbering system, and recording process changed. On February 25, 1925, Columbia began recording with the electric recording process licensed from Western Electric.[13]

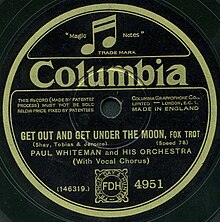

In 1926, Columbia acquired Okeh Records and its growing stable of jazz and blues artists, including Louis Armstrong and Clarence Williams. Columbia had already built a catalog of blues and jazz artists, including Bessie Smith in their 14000-D Race series. Columbia also had a successful "Hillbilly" series (15000-D) with Dan Hornsby among others. By 1927, the "Sweet Jazz" bandleader Guy Lombardo also joined Columbia and recorded forty five 78 rpm's by 1931.[14] In 1928, Paul Whiteman, the nation's most popular orchestra leader, left Victor to record for Columbia. During the same year, Columbia executive Frank Buckley Walker pioneered some of the first country music or "hillbilly" genre recordings with the Johnson City sessions in Tennessee, including artists such as Clarence Horton Greene and "Fiddlin'" Charlie Bowman. He followed that with a return to Tennessee the next year, as well as recording sessions in other cities of the South. Moran and Mack as The Two Black Crows 1926 recording 'The Early Bird Catches the Worm' sold 2.5 million copies.[15]

Columbia ownership separation (1931–1936)

[edit]The repercussions of the stock market Crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression led to the near collapse of the entire recording industry and, in March 1931, J.P Morgan, the major shareholder, steered the Columbia Graphophone Company (along with Odeon records and Parlophone, which it had owned since 1926) into a merger with the Gramophone Company ("His Master's Voice") to form Electric and Musical Industries Ltd (EMI).[16][17][18] Since the Gramophone Company (HMV) was now a wholly owned subsidiary of Victor, and Columbia in America was a subsidiary of UK Columbia, Victor now technically owned its largest rival in the US.[16] To avoid antitrust legislation, EMI had to sell off its US Columbia operation, which continued to release pressings of matrices made in the UK.[16]

In December, 1931, the U.S. Columbia Phonograph Company, Inc. was acquired by the Grigsby-Grunow Company, the manufacturers of Majestic radios and refrigerators. When Grigsby-Grunow declared bankruptcy in November 1933, Columbia was placed in receivership, and in June 1934, the company was sold[19] to Sacro Enterprises Inc. ("Sacro") for $70,000. Sacro was incorporated a few days before the sale in New York. Public documents do not contain any names. Many suspect that it was a shell corporation set up by Consolidated Films Industries, Inc. ("CFI") to hold the Columbia stock, while its subsidiary, American Record Corporation ("ARC"), operated the label. This assumption grew out of the ease which CFI later exhibited in selling Columbia in 1938.[20]

As southern gospel developed, Columbia had astutely sought to record the artists associated with the emerging genre; for example, Columbia was the only company to record Charles Davis Tillman. Most fortuitously for Columbia in its Depression Era financial woes, in 1936 the company entered into an exclusive recording contract with the Chuck Wagon Gang, a hugely successful relationship which continued into the 1970s. A signature group of southern gospel, the Chuck Wagon Gang became Columbia's bestsellers with at least 37 million records,[21] many of them through the aegis of the Mull Singing Convention of the Air sponsored on radio (and later television) by southern gospel broadcaster J. Bazzel Mull (1914–2006).

By 1937–38, the record business in America was finally recovering from the near-death blow of the Great Depression, at least for RCA Victor and Decca, but privately, there were doubts about the survival of ARC.[22] In a 1941 court case brought by unhappy shareholders of Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc. ("CBS"), Edward Wallerstein, a high executive with RCA Victor from 1932 thru 1938, was asked to comment on ARC. "The chief value was that the record industry had come back tremendously, especially in the case of two other record companies; and the American Record Company, with all its facilities, had not, so far as I could learn, increased its business in any degree at all in the previous six years."[2]

CBS takes over (1938–1947)

[edit]

On December 17, 1938, the ARC, including the Columbia label in the U.S., was acquired by William S. Paley of the Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc. for US$700,000,.[2][1] ten times the price ARC paid in 1934, which would later spark lawsuits by disgruntled shareholders. (Columbia Records had originally co-founded CBS in 1927 along with New York talent agent Arthur Judson, but soon cashed out of the partnership leaving only the name; Paley acquired the fledgling radio network in 1928.) On January 3, 1939, Wallerstein left RCA Victor to become president of the CBS phonograph subsidiary, a position he would hold for twelve years. CBS kept the ARC name for three months. then on April 4, it amended the New York Department of State record of "Columbia Phonograph Company, Inc.," naming several of its own employees to directorships, and announced in a press release, "The American Record Co. tag is discarded". Columbia Records was actually reborn on May 22, 1939, as "Columbia Recording Corporation, Inc.", a Delaware corporation.[23] The NYDOS shows a later incorporation date of April 4, 1947. This corporation changed its name to Columbia Records, Inc. on October 11, 1954, and reverted to Columbia Recording Corporation on January 2, 1962.[24] The Columbia trademark remained under Columbia Records, Inc. of Delaware, filed back in 1929.[25] Brothers Ike and Leon Levy owned stakes in CBS.[26]

On August 30, 1939, Columbia replaced its $.75 Brunswick record for a $.50 Columbia label.[27]

In 1947, the company was renamed Columbia Records Inc.[28] and founded its Mexican record company, Discos Columbia de Mexico.[29] 1948 saw the first classical LP Nathan Milstein's recording of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. Columbia's new 33 rpm format quickly spelled the death of the classical 78 rpm record and for the first time in nearly fifty years, gave Columbia a commanding lead over RCA Victor Red Seal.[30][31]

The LP record (1948–1959)

[edit]Columbia's president Edward Wallerstein was instrumental in steering Paley towards the ARC purchase. He set his talents to his goal of hearing an entire movement of a symphony on one side of an album. Ward Botsford writing for the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Issue of High Fidelity Magazine relates: "He was no inventor—he was simply a man who seized an idea whose time was ripe and begged, ordered, and cajoled a thousand men into bringing into being the now accepted medium of the record business." Despite Wallerstein's stormy tenure, in June 1948, Columbia introduced the Long Playing "microgroove" LP record format (sometimes written "Lp" in early advertisements), which rotated at 33⅓ revolutions per minute, to be the standard for the gramophone record for forty years. CBS research director Dr. Peter Goldmark played a managerial role in the collaborative effort, but Wallerstein credits engineer William Savory with the technical prowess that brought the long-playing disc to the public.[32]

By the early 1940s, Columbia had been experimenting with higher fidelity recordings, as well as longer masters, which paved the way for the successful release of the LPs in 1948. One such record that helped set a new standard for music listeners was the 10" LP reissue of The Voice of Frank Sinatra, originally released on March 4, 1946, as an album of four 78 rpm records, which was the first pop album issued in the new LP format. Sinatra was arguably Columbia's hottest commodity and his artistic vision combined with the direction Columbia were taking the medium of music, both popular and classic, were well suited. The Voice of Frank Sinatra was also considered to be the first genuine concept album. Since the term "LP" has come to refer to the 12-inch 33+1⁄3 rpm vinyl disk, the first LP is the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor played by Nathan Milstein with Bruno Walter conducting the New York Philharmonic (then called the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York), Columbia ML 4001, found in the Columbia Record Catalog for 1949, published in July 1948. The other "LP's" listed in the catalog were in the 10 inch format starting with ML 2001 for the light classics, CL 6001 for popular songs and JL 8001 for children's records.[32] The Library of Congress in Washington DC now holds the Columbia Records Paperwork Archive which shows the Label order for ML 4001 being written on March 1, 1948. One can infer that Columbia was pressing the first LPs for distribution to their dealers for at least 3 months prior to the introduction of the LP on June 21,[33] 1948.[34]

1950s

[edit]

In 1951, Columbia US began issuing records in the 45 rpm format RCA Victor had introduced two years earlier.[35] The same year, Ted Wallerstein retired as Columbia Records chairman;[36] and Columbia US also severed its decades-long distribution arrangement with EMI and signed a distribution deal with Philips Records to market Columbia recordings outside North America.[37] EMI continued to distribute Okeh and later Epic label recordings until 1968. EMI also continued to distribute Columbia recordings in Australia and New Zealand. American Columbia was not happy with EMI's reluctance to introduce long playing records.[38]

In 1953, Columbia formed a new subsidiary label Epic Records.[39] 1954 saw Columbia end its distribution arrangement with Sparton Records and form Columbia Records of Canada.[40] To enhance its country music stable, which already included Marty Robbins, Ray Price and Carl Smith, Columbia bid $15,000 for Elvis Presley's contract from Sun Records in 1955.[41] Presley's manager, Colonel Tom Parker, turned down their offer and signed Presley with RCA Victor.[41] However, Columbia did sign two Sun artists in 1958: Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins.[41]

With 1954, Columbia U.S. decisively broke with its past when it introduced its new, modernist-style "Walking Eye" logo,[42] designed by Columbia's art director S. Neil Fujita. This logo actually depicts a stylus (the legs) on a record (the eye); however, the "eye" also subtly refers to CBS's main business in television, and that division's iconic Eye logo. Columbia continued to use the "notes and mike" logo on record labels and even used a promo label showing both logos until the "notes and mike" was phased out (along with the 78 in the US) in 1958. In Canada, Columbia 78s were pressed with the "Walking Eye" logo in 1958. The original Walking Eye was tall and solid; it was modified in 1961.[43] Although the big band era had passed, Columbia had Duke Ellington under contract for several years, capturing the historic moment when Ellington's band provoked a post-midnight frenzy (followed by international headlines) at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, which proved a boost to a bandleader whose career had stalled. Under new head producer George Avakian, Columbia became the most vital label to the general public's appreciation and understanding (with help from Avakian's prolific and perceptive play-by-play liner notes) of jazz, releasing a series of LP's by Louis Armstrong, but also signing to long-term contracts Dave Brubeck and Miles Davis, the two modern jazz artists who would in 1959 record albums that remain—more than sixty years later—among the best-selling jazz albums by any label—viz., Time Out by the Brubeck Quartet and, to an even greater extent, Kind of Blue by the Davis Sextet, which, in 2003, appeared as number 12 in Rolling Stone's list of the "500 Greatest Albums Of All Time".[44]

In the same year, former Columbia A&R manager Goddard Lieberson was promoted to President of the entire CBS recording division, which included Columbia and Epic, as well as the company's various international divisions and licensees. Under his leadership the corporation's music division soon overtook RCA Victor as the top recording company in the world, boasting a star-studded roster of artists and an unmatched catalogue of popular, jazz, classical and stage and screen soundtrack titles. Lieberson, who had joined Columbia as an A&R manager in 1938, was known for both his personal elegance and his dedication to quality, overseeing the release of many hugely successful albums and singles, as well as championing prestige releases that sold relatively poorly, and even some titles that had limited appeal, such as complete editions of the works of Arnold Schoenberg and Anton von Webern. One of his first major successes was the original Broadway cast album of My Fair Lady, which sold over 5 million copies worldwide in 1957, becoming the most successful LP ever released up to that time. Lieberson also convinced long-serving CBS President William S. Paley to become the sole backer of the original Broadway production, a $500,000 investment which subsequently earned the company some $32 million in profits.[45]

In October 1958, Columbia, in time for the Christmas season, put out a series of "Greatest Hits" packages by such artists as Johnny Mathis, Doris Day, Guy Mitchell, Johnnie Ray, Jo Stafford, Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney, Frankie Laine and the Four Lads; months later, it put out another Mathis compilation as well as that of Marty Robbins. Only Mathis' compilations charted, since there were only 25 positions on Billboard's album charts at the time.[46]

Stereo

[edit]Although Columbia began recording in stereo in 1956, stereo LPs did not begin to be manufactured until 1958. One of Columbia's first stereo releases was an abridged and re-structured performance of Handel's Messiah by the New York Philharmonic and the Westminster Choir conducted by Leonard Bernstein (recorded on December 31, 1956, on 1⁄2-inch tape, using an Ampex 300-3 machine).[47]

Columbia released its first pop stereo albums in the summer of 1958. All of the first dozen or so were stereo versions of albums already available in mono. It was not until September 1958, that Columbia began simultaneous mono/stereo releases. Mono versions of otherwise stereo recordings were discontinued in 1968. To celebrate the 10th anniversary of the introduction of the LP, in 1958 Columbia initiated the "Adventures in Sound" series that showcased music from around the world.[48][49]

The 1960s

[edit]Outing of "deep groove"

[edit]By the latter half of 1961, Columbia started using pressing plants with newer equipment. The "deep groove" pressings were made on older pressing machines, where the groove was an artifact of the metal stamper being affixed to a round center "block" to assure the resulting record would be centered. Newer machines used parts with a slightly different geometry, that only left a small "ledge" where the deep groove used to be. This changeover did not happen all at once, as different plants replaced machines at different times, leaving the possibility that both deep groove and ledge varieties could be original pressings. The changeover took place starting in late 1961.[50]

CBS Records

[edit]

In 1961, CBS ended its arrangement with Philips Records and formed its own international organization, CBS Records International, in 1962. This subsidiary label released Columbia recordings outside the US and Canada on the CBS label (until 1964 marketed by Philips in Britain).[51]

While this happened, starting in late 1961, both the mono and the stereo labels of domestic Columbia releases started carrying a small "CBS" at the top of the label. This was not something that changed at a certain date, but rather, pressing plants were told to use up the stock of old (pre-CBS) labels first, resulting in a mixture of labels for some given releases. Some are known with the CBS text on mono albums, and not on stereo of the same album, and vice versa; diggings brought up pressings with the CBS text on one side and not on the other. Many, but certainly not all, of the early numbers with the "ledge" variation (i.e., no deep groove), had the small "CBS".[52] This text would be used on the Columbia labels until June 1962.[53]

Columbia's Mexican unit, Discos Columbia, was renamed Discos CBS.[51]

Mitch Miller on television

[edit]In 1961, Columbia's music repertoire was given an enormous boost when Mitch Miller, its A&R manager and bandleader, became the host of the variety series Sing Along with Mitch on NBC.[54] The show was based on Miller's 'folksy' but appealing 'chorus' style performance of popular standards. During its four-season run, the series promoted Miller's "Singalong" albums, which sold over 20 million units, and received a 34% audience share when it was cancelled in 1964.[55]

Bob Dylan

[edit]In September 1961, CBS A&R manager John Hammond was producing the first Columbia album by folk singer Carolyn Hester, who invited a friend to accompany her on one of the recording sessions. It was here that Hammond first met Bob Dylan, whom he signed to the label, initially as a harmonica player.[56] Dylan's self-titled debut album was released in March 1962 and sold only moderately.[57] Some executives in Columbia dubbed Dylan "Hammond's folly" and suggest that Dylan be dropped from the label.[58]

Over the course of the 1960s, Dylan achieved a prominent position in Columbia. His early folk songs were recorded by many acts and became hits for Peter, Paul & Mary and The Turtles.[59]

Rock and roll

[edit]When the British Invasion arrived in January 1964, Columbia had no rock musicians on its roster except for Dion, who was signed in 1963 as the label's first major rock star, and Paul Revere & the Raiders who were also signed in 1963. The label released a merseybeat album, The Exciting New Liverpool Sound (Columbia CL-2172, issued in mono only). Terry Melcher, son of Doris Day, produced the hard driving "Don't Make My Baby Blue" for Frankie Laine, who had gone six years without a hit record. The song reached No. 51 on the pop chart and No. 17 on the easy listening chart.[56]

Melcher and Bruce Johnston discovered and brought to Columbia the Rip Chords, a vocal group consisting of Ernie Bringas and Phil Stewart, and turned it into a rock group through production techniques. The group had hits in "Here I Stand", a remake of the song by Wade Flemons, and "Hey Little Cobra".[56]

Ascension of Clive Davis

[edit]When Mitch Miller retired in 1965,[60] Columbia was at a turning point. Miller's disdain for rock and roll and pop rock had dominated Columbia's A&R policy. Sales of Broadway soundtracks and Mitch Miller's singalong series were waning. Pretax earnings had flattened to about $5 million annually.[55] The label's only significant "pop" acts at the time were Bob Dylan, the Byrds, Paul Revere & the Raiders and Simon & Garfunkel. In its catalogue were other genres: classical, jazz and country, along with a select group of R&B artists, among them Aretha Franklin.[56] Most historians observed that Columbia had problems marketing Franklin as a major talent in the R&B genre, which led to her leaving the label for Atlantic Records in 1967.[61][62]

In 1967, Brooklyn-born lawyer Clive Davis became president of Columbia. Following the appointment of Davis, the Columbia label became more of a rock music label, thanks mainly to Davis's fortuitous decision to attend the Monterey International Pop Festival, where he spotted and signed several leading acts including Janis Joplin. Joplin led the way for several generations of female rock and rollers. However, Columbia/CBS still had a hand in traditional pop and jazz and one of its key acquisitions during this period was Barbra Streisand. She released her first solo album on Columbia in 1963 and remains with the label to this day. Additionally, the label kept Miles Davis on the roster, and his late 1960s recordings, In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, pioneered a fusion of jazz and rock music.[63]

Simon & Garfunkel

[edit]Arguably the most commercially successful Columbia pop act of this period, other than Bob Dylan, was Simon & Garfunkel. The duo scored a surprise No. 1 hit in 1965 when Columbia producer Tom Wilson, inspired by the folk-rock experiments of Dylan, The Byrds and others, added drums and bass to the duo's earlier recording of "The Sound of Silence" without their knowledge or approval. Indeed, the duo had already broken up some months earlier, discouraged by the poor sales of their debut LP, and Paul Simon had relocated to the UK, where he only found out about the single being a hit via the music press. The dramatic success of the song prompted Simon to return to the US; the duo reformed, and they soon became one of the flagship acts of the folk-rock boom of the mid-1960s. Their next album, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme, went to No. 4 on the Billboard album chart. The duo subsequently had a Top 20 single, "A Hazy Shade of Winter", but progress slowed during 1966–67 as Simon struggled with writer's block and the demands of constant touring. They shot back to the top in 1968 after Simon agreed to write songs for the Mike Nichols film The Graduate. The resulting single, "Mrs. Robinson", became a smash hit. Both The Graduate soundtrack and Simon & Garfunkel's next studio album, Bookends, were major hits on the album chart, with combined total sales in excess of five million copies. Simon and Garfunkel's fifth and final studio album, Bridge over Troubled Water (1970), reached number one in the US album charts in January 1970 and became one of the most successful albums of all time.[64]

Hoyt Axton and Tom Rush

[edit]Davis lured artists Hoyt Axton and Tom Rush to Columbia in 1969, and both were given what was known as "the pop treatment" by the label. Hoyt Axton had been a folk/blues singer-songwriter since the early 1960s, when he made several albums for Horizon, then Vee-Jay. By the time he joined Columbia, he had mixed successful pop songs like "Greenback Dollar", with hard rock songs for Steppenwolf, such as "The Pusher", which was used in the film Easy Rider in the same year. When he landed at Columbia, his album My Griffin Is Gone was described as "the poster child for 'overproduced,' full of all kinds of instruments and even strings".[65]

Tom Rush had always been the "storyteller" or "balladeer" type of folk artist, before and after his stint with Columbia, to which Rush was lured from Elektra. As with Axton, Rush was given "the treatment" on his self-titled Columbia debut. The multitude of instruments added to his usual solo guitar were all done "tastefully", of course, but was not really on par with Rush's audience expectations. He commented to record label historian Mike Callahan:

Well, when you're in the studio, they bring out all these "sweeteners" and things they have, and while you're there, you say, yeah, that sounds good. But then you get the album home and you almost can't hear yourself under all that.[65]

The 1970s

[edit]Catalog numbers

[edit]The Columbia album series began in 1951 with album GL-500 (CL-500) and reached an awkward milestone in 1970, when the stereo numbering sequence reached CS-9999, assigned to the Patti Page album Honey Come Back. This presented a catalog numbering system challenge as Columbia had used a four-digit catalog number for 13 years, and CS-10000 seemed cumbersome. Columbia decided to start issuing albums at CS-1000 instead, preserving the four-digit catalog number. However, this resulted in the reuse of numbers previously used in 1957–58, although the prefix was now different. In July 1970, the cataloging department implemented a new system, combining all their labels into a unified catalog numbering system starting with 30000, with the prefix letter indicating the label: C for Columbia, E for Epic, H for Harmony (budget reissue line), M for Columbia Masterworks, S for movie soundtrack and original Broadway cast albums, Y for Columbia Odyssey, and Z for every other label that CBS distributed (collectively referred to as CBS Associated). The prefix letter G was also used for two album sets—or the number of records in the set after the label letter, such as KC2.[66] The first CBS album released under the new system was The Elvin Bishop Group's self-titled album on Fillmore Records, assigned with F 30001 (the earliest Fillmore albums had the 'F' prefix, rather than a 'Z'), while the first actual Columbia release under the system was Herschel Bernardi's Show Stopper, assigned with C 30004.[67]

In September 1970, under the guidance of Clive Davis, Columbia Records entered the West Coast rock market, opening a state-of-the art recording studio (which was located at 827 Folsom St. in San Francisco and later morphed into the Automatt) and establishing an A&R head and office in San Francisco at Fisherman's Wharf, headed by George Daly, a producer and artist for Monument Records (who inked a distribution deal with Columbia at the time) and a former bandmate of Nils Lofgren and Roy Buchanan. The recording studio operated under CBS until 1978.[68]

Yetnikoff becomes president

[edit]In 1975, Walter Yetnikoff was promoted to become President of Columbia Records, and his vacated position as President of CBS Records International was filled by Dick Asher. At this point, according to music historian Frederic Dannen, the shy and introverted Yetnikoff began to transform his personality, becoming (in Asher's words) "wild, menacing, crude, and above all, very loud". In Dannen's view, Yetnikoff was probably over-compensating for his naturally sensitive and generous personality, and that he had little hope of being recognised as a "record man" (someone with a musical ear and an intuitive understanding of current trends and artists' intentions) because he was tone-deaf, so he instead determined to become a "colourful character".[69] Yetnikoff soon became notorious for his violent temper and regular tantrums: "He shattered glassware, spewed a mixture of Yiddish and barnyard epithets, and had people physically ejected from the CBS building."[70]

In 1976, Columbia Records of Canada was renamed CBS Records Canada Ltd.[40]

Dick Asher vs "The Network"

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

During this period, Columbia scored a Top 40 hit with the Pink Floyd single "Another Brick in the Wall", and its parent album The Wall would spend four months at No. 1 on the Billboard LP chart in early 1980, but few in the industry knew that Dick Asher was in fact using the single as a covert experiment to test the extent of the pernicious influence of The Network – by not paying them to promote the new Pink Floyd single. The results were immediate and deeply troubling – not one of the major radio stations in Los Angeles would program the record, despite the fact that the group was in town, performing the first seven concerts on their elaborate The Wall Tour at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena to rave reviews and sold-out crowds. Asher was already worried about the growing power of The Network, and the fact it operated entirely outside the control of the label, but he was profoundly dismayed to realize that "The Network" was in effect a huge extortion racket, and that the operation could well be linked to organized crime – a concern vehemently dismissed by Yetnikoff, who resolutely defended the "indies" and declared them to be "mensches". But Dick Asher now knew that The Network's real power lay in their ability to prevent records from being picked up by radio, and as an experienced media lawyer and a loyal CBS employee, he was also acutely aware that this could become a new payola scandal which had the potential to engulf the entire CBS corporation, and that the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) could even revoke CBS' all-important broadcast licenses if the corporation was found to be involved in any illegality.[71]

The 1980s and sale to Sony

[edit]In 1988, the CBS Records Group, including the Columbia Records unit, was acquired by Sony, which re-christened the parent division Sony Music Entertainment in 1991. As Sony only had a temporary license on the CBS Records name, it then acquired the rights to the Columbia trademarks (Columbia Graphophone) outside the U.S., Canada, Spain (trademark owned by BMG) and Japan (Nippon Columbia) from EMI, a firm which generally had not used them since the early 1970s. The CBS Records label was officially renamed Columbia Records on January 1, 1991, worldwide except Spain (where Sony got the rights in 2004 by forming a joint venture with BMG[72]) and Japan.[73]

The 1990s–present

[edit]American talent manager Will Botwin was recruited in 1996 to serve as a Senior Vice President. In 1998, he was appointed Executive Vice President/General Manager and worked closely with many of the label's established artists, as well as newer performers such as Microdisney and Five For Fighting.[74] In 2002, Botwin was promoted to President of the Columbia Records Group;[75] he was appointed Chairman in 2005.[76] In 2006, he left Columbia to head Red Light Management and its associated ATO Records.[74]

Columbia Records remains a premier subsidiary label of Sony Music Entertainment. In 2009, during the re-consolidation of Sony Music, Columbia was partnered with its Epic Records sister to form the Columbia/Epic Label Group[77] under which it operated as an imprint. In July 2011, as part of further corporate restructuring, Epic was split from the Columbia/Epic Group as Epic took in multiple artists from Jive Records.[78]

As of March 2013, Columbia Records was home to 90 artists such as Lauren Jauregui, Robbie Williams, Calvin Harris and Daft Punk.[79]

On January 2, 2018, Ron Perry was named as the chairman and CEO of Columbia Records.[80] In January 2023, Jennifer Mallory was appointed President.[81]

Logos and branding

[edit]The acquisition of rights to the Columbia trademarks by EMI (including the "Magic Notes" logo) presented the company with a dilemma of which logo to use. For much of the 1990s, Columbia released its albums without a logo, just the "COLUMBIA" word mark in the Bodoni Classic Bold typeface.[82] Columbia experimented with bringing back the "Notes and Mic" logo but without the CBS mark on the microphone. That logo is currently used in the "Columbia Jazz" series of jazz releases and reissues.[83]

List of Columbia Records artists

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (March 2024) |

As of 2024, the current Columbia Records roster includes Barbra Streisand, Bruce Springsteen, Celine Dion, Beyoncé, Jennie, Adele, Rosalía, Harry Styles, Miley Cyrus, Lil Nas X, Blink-182, Addison Rae, JoJo Siwa, Dove Cameron, Central Cee, Chlöe, Halsey, IVE and many more. In October 2012, there were 85 recording artists signed to Columbia Records.[84]

Affiliated labels

[edit]American Recording Company (ARC)

[edit]During August 1978 Maurice White, founder and leader of the band Earth, Wind & Fire, re-launched the American Recording Company (ARC). In addition to White's Earth, Wind & Fire, the Columbia Records-distributed label artist roster included successful R&B and pop singer Deniece Williams, jazz-fusion group Weather Report, and R&B trio the Emotions.[85][86]

Recording studios

[edit]Columbia Records operated recording studios, the most notable of which were in New York City, Nashville, Hollywood and San Francisco. Columbia's first recording studio was established in 1913, after the company moved into the Woolworth Building in Manhattan, the tallest building in the world at the time.[87] In 1917, Columbia used this studio to make one of the earliest jazz records, by the Original Dixieland Jass Band.[88][89]

7th Avenue, New York

[edit]In 1939, Columbia established Studio A at 799 Seventh Avenue in New York City.[23]

52nd Street, New York

[edit]Studio B and Studio E were located in the CBS Studio Building at 49 East 52nd Street in New York City – on the second and fifth floor, respectively.[90]

30th Street, New York

[edit]In 1948, Columbia built additional new studios at 207 East 30th Street in Manhattan's Murray Hill district, naming them Studio C and Studio D. This complex, nicknamed "The Church" due to it having been built within an 1875 building that was originally constructed as a Christian church, was considered by some in the music industry to be the best-sounding room of its time, and many consider it to have been the greatest recording studio in history.[90][91]

Columbia Studios, Nashville

[edit]In 1962, Columbia Records purchased the Bradley Studios in Nashville, Tennessee (also known as the Quonset Hut), the first recording studio in what would become Nashville's Music Row district when first established by Harold and Owen Bradley in 1954. Renamed Columbia Studios, the company replaced Bradley Studio A with a building containing a newer, larger studio A, mixing and mastering studios, and administrative offices. Columbia operated these studios from 1962 through 1982, when they were converted into office space.[92] Philanthropist Mike Curb bought the structure in 2006 and restored it; it is now a recording classroom for Belmont University's Mike Curb College of Entertainment & Music Business.[92]

Liederkranz Hall Studio, New York

[edit]Columbia also recorded in the highly respected Liederkranz Hall, at 111 East 58th Street between Park and Lexington Avenues, in New York City, it was built by and formerly belonged to a German cultural and musical society, The Liederkranz Society, and used as a recording studio (Victor also recorded in Liederkranz Hall in the late 1920s).[90][93][94][95] The producer Morty Palitz had been instrumental in convincing Columbia Records to begin to use the Liederkranz Hall studio for recording music, additionally convincing the conductor Andre Kostelanetz to make some of the first recordings in Liederkranz Hall which until then had only been used for CBS Symphony radio shows.[96] In 1949, the large Liederkranz Hall space was physically rearranged to create four television studios.[90][97]

Executives

[edit]- Ron Perry – Chairman & CEO

- Jenifer Mallory – GM

- Stephen Russo – EVP & CFO

- Abou "Bu" Thiam – EVP

- Edward Wallerstein – Chairman & CEO (1939–1951)

See also

[edit]- Jim Flora, successor to Alex Steinweiss and legendary illustrator for the label during the 1940s

- List of record labels

- Sony BMG

- Alex Steinweiss, the label's Art Director from 1938 to 1943, inventor of the illustrated album cover and the LP sleeve

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Frank Walker". Variety. December 21, 1938. p. 24. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Appeals, New York (State) Court of (1941). New York Court of Appeals. Records and Briefs.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. September 17, 1955. p. 35. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Ben Sisario (October 30, 2012). "From One Mine, the Gold of Pop History". The New York Times. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ "125 Years of Columbia Records – An Interactive Timeline". Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Emile Berliner and the Birth of the Recording Industry: The Gramophone". Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Labels - Sony Music".

- ^ Hazelcorn, Howard (1976). A Collector's Guide to the Columbia Spring-Wound Cylinder Graphophone (1 ed.). Antique Phonograph Monthly. pp. 10, 13.

- ^ a b "Edward Easton". IEEE. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Bilton, Lynn (1998). "Hail, Columbia: A fresh book at last gives Edward Easton and his Graphophone company their due". Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ Gracyk, Tim (October 11, 1904). "Tim Gracyk's Phonographs, Singers, and Old Records – How Late Did Columbia Use Brown Wax?". Gracyk.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ Rye, Howard; Kernfeld, Barry (2002). Kernfeld, Barry (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). New York: Grove's Dictionaries Inc. p. 172. ISBN 1-56159-284-6.

- ^ Brooks, Tim (ed.), Columbia Corporate History: Electrical Recording and the Late 1920s, Columbia Master Book Discography, Volume I (Online ed.), Discography of American Historical Recordings (DAHR)

- ^ The Canadian Encyclopedia: "Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians" Mookg, Edward B. (6 April 2008 rev. 4 March 2015) on thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en

- ^ Murrells, Joseph (1978). The book of golden discs. Internet Archive. London : Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 978-0-214-20512-5.

- ^ a b c Brooks, Tim (ed.), Columbia Corporate History: Market Crash, 1929, and the Early 1930s, Columbia Master Book Discography, Volume I (Online ed.), Discography of American Historical Recordings (DAHR) See also Notes section.

- ^ Walworth, Julia (2005). "Sir Louis Sterling and his library". Jewish Historical Studies. 40. Jewish Historical Society of England: 161. JSTOR 24027031.

- ^ "EMI: A Brief History". BBC News. January 24, 2000. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ "Grigsby Radio Holdings Sold". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Associated Press. June 17, 1936. p. 24 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brooks, Tim (March 22, 2013). "360 Sound: The Columbia Records Story. Columbia Records: Pioneer in Recorded Sound: America's Oldest Record Company, 1886 to the Present". Book Reviews. ARSC Journal. 44 (1): 133.

- ^ "Solid Gospel series brings Chuck Wagon Gang to Renaissance Center". Archived from the original on August 10, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Wilentz, Sean (2012). 360 Sound the Columbia Records Story. New York: Chronicle Books. pp. 90–95. ISBN 9781452107561.

- ^ a b Marmorstein, Gary (2007). The label : the story of Columbia Records. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press Avalon Publishing Group. pp. 100–110. ISBN 978-1560257073.

- ^ "Public Inquiry". apps.dos.ny.gov. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ "Division of Corporations – Filing". icis.corp.delaware.gov. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ CBS reflections in a Bloodshot Eye Metz World Radio History

- ^ "Columbia drops its Brunswick label". Variety. August 30, 1939. p. 241. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ "Columbia Records paperwork collection". Library of Congress.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. March 16, 1963. p. 60. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ D. Kern Holoman The Orchestra: A Very Short Introduction 2012 Page 107 "The first classical LP was the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto with Nathan Milstein, Bruno Walter, and the New York Philharmonic-Symphony, Columbia ML-4001. RCA capitulated in 1950, leaving 45s as the medium of choice for pop singles."

- ^ John F. Morton Backstory in Blue: Ellington at Newport '56 2008 Page 49 "1947.. The following year Columbia made what it regarded as record history, introducing the first twelve-inch LP, Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in E minor, with violinist Nathan Milstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, Bruno Walter ... Within a year and a half of the introduction of the LP, Columbia had sold twice as many Masterworks as RCA was selling of Red Seal. RCA had begun to lose some its artists. Some, like opera tenor (sic), Ezio Pinza, would go to Columbia..."

- ^ a b Columbia Record Catalog 1949. Columbia Records Inc. pp. 1–20.

- ^ The First Long-Playing Disc Library of Congress (Congress.gov) (accessdate 21 June 2021)

- ^ Library of Congress Columbia Records Paperwork Box 121

- ^ "Record Collector's Resource: A History of Records". Cubby.net. February 26, 1917. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. September 26, 1970. p. 10. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ "Mitch Miller And His Orchestra And Chorus – Mitch Miller – Philips – UK". 45cat. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ^ John Broven (February 26, 2009). Record Makers and Breakers: Voices of the Independent Rock 'n' Roll Pioneers. University of Illinois Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-252-03290-5. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. September 19, 1953. p. 16. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ a b "Sony Music Entertainment Inc | The Canadian Encyclopedia". thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010.

- ^ a b c Worth, Fred (1992). Elvis: His Life from A to Z. Outlet. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-517-06634-8.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. September 11, 1954. p. 45. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ "columbia representative". Billboard. August 14, 1961.

- ^ "Kind of Blue". Rollingstone.com. February 9, 2003. Archived from the original on March 17, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ^ Dannen (1991), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Watts, Randy; Callahan, Mike; Edwards, David; Eyries, Patrice (October 24, 2015). "Columbia Album Discography, Part 8 (CL 1200 to CL 1299) 1958-1959". Both Sides Now Publications. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ This stereo LP Box Set (2 LPs) have released first as M2S-603 (MS 6038-9) in 1958.

- ^ Billboard (January 6, 1958). "Columbia's 1958 Tee-Off Cues Big Product Campaign: Program Set to Tie in with LP Disk's 10th Anniversary Year". Billboard. p. 15.

- ^ Borgerson, Janet (2017). Designed for Hi-Fi Living : The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America. Schroeder, Jonathan E., 1962. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 283–297. ISBN 9780262036238. OCLC 958205262.

- ^ Watts, Randy; Callahan, Mike; Edwards, David; Eyries, Patrice (October 28, 2015). "Columbia Album Discography, Part 12 (CL 1600-1699/CS 8400–8499) 1961–1962". Both Sides Now Publications. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ a b Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. March 16, 1963. p. 40. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ Watts, Randy; Callahan, Mike; Edwards, David; Eyries, Patrice (October 29, 2015). "Columbia Album Discography, Part 13 (CL 1700-1799/CS 8500–8598) 1961–1962". Both Sides Now Publications. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Watts, Randy; Callahan, Mike; Edwards, David; Eyries, Patrice (October 30, 2015). "Columbia Album Discography, Part 14 (CL 1800-1899/CS 8600–8699) 1960–1961". Both Sides Now Publications. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Bessman, Jim; Cox, Tony; Miller, Mitch (August 3, 2010). "Remembering Singing Along With Mitch Miller". Talk of the Nation. NPR. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Dannen (1991), p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d Watts, Randy; Callahan, Mike; Edwards, David; Eyries, Patrice (November 2, 2015). "Columbia Album Discography, Part 17 (CL 2100-2199/CS 8900–8999) 1963–1964". Both Sides Now Publications. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ^ "20 Things You Might Not Know About Bob Dylan's Debut Album – NME". NME. March 19, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ "50 Years Ago Today: Bob Dylan Released His Debut Album". Rolling Stone. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ Willis, Amy (September 17, 2009). "Peter, Paul and Mary: Top songs of all time". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ^ Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. December 11, 1965. p. 3. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 52 – The Soul Reformation: Phase three, soul music at the summit. [Part 8] : UNT Digital Library" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ^ Edwards, David; Callahan, Mike. "Atlantic Records Story". www.bsnpubs.com. Retrieved August 23, 2011.

- ^ Jurek, Thom. "Bitches Brew". AllMusic. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Bridge Over Troubled Water". AllMusic. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ^ a b Watts, Randy; Callahan, Mike; Edwards, David; Eyries, Patrice (November 10, 2015). "Columbia Album Discography, Part 27 (K)CS 9900–9999 (1969–1970)". Both Sides Now Publications. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ^ "CBS LPs – US unified numbering system". Global Dog Productions. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ "LP Discography for CBS Records US combined numbering system 30000-30499". Global Dog Productions. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Heather (2006). If These Halls Could Talk: A Historical Tour Through San Francisco Recording Studios. Thomson Course Technology. pp. 90–94. ISBN 1-59863-141-1.

- ^ Dannen (1991), p. 19.

- ^ Dannen (1991), p. 21.

- ^ Dannen (1991), pp. 4–27.

- ^ [1] Archived February 4, 2004, at the Wayback Machine[dead link]

- ^ "CBS Records Changes Name". The New York Times. Reuters. October 16, 1990. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ a b "Will Botwin Joins Red Light". ENCORE. CelebrityAccess. December 14, 2006. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- ^ "Sony Music Gets Ready for Black Friday". Fox News. December 1, 2011. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Gallo, Phil (February 8, 2005). "Columbia chair adjusted". Variety. Archived from the original on November 28, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ "Sony Music Entertainment to be Exclusive Music Provider for ESPN's Winter X Games 13". Sony Music. October 27, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Halperin, Shirley (July 12, 2011). "L.A. Reid's First Week at Epic Has Some Staffers Feeling 'Energized'". Billboard.biz. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Columbia Records Music Moving Forward. Columbiarecords.com. Retrieved on July 16, 2013.

- ^ "Sony names new CEO of Columbia Records", Anthony Noto, New York Business Journal, January 2, 2018, retrieved on January 2, 2018.

- ^ "Jenifer Mallory Named President of Columbia Records". January 31, 2023.

- ^ "Columbia Records Online – USA". February 8, 1999. Archived from the original on February 8, 1999. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ "Columbia Jazz – Main Nav". Columbiarecords.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 1998. Retrieved December 31, 2009.

- ^ "Columbia Records artists". Columbia Records. Sony Music Entertainment. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ New ARC Columbia Label on debut. Vol. 90. Billboard Magazine. August 5, 1978. p. 19.

- ^ Maurice White's Prowling for Acts, Building Studios. Vol. 91. Billboard Magazine. July 14, 1979. p. 26.

- ^ Hoffmann, Frank, Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound, New York & London : Routledge, 1993 & 2005, Volume 1. Cf. p.212, article on "Columbia (Label)".

- ^ Cogan, Jim (2003). Temples of Sound. San Francisco: Chronicle Books LLC. pp. 181–191. ISBN 0-8118-3394-1.

- ^ "The Woolworth Building", NYC Architecture

- ^ a b c d Simons, David (2004). Studio Stories – How the Great New York Records Were Made. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-817-9.

- ^ Milner, Greg, Perfecting Sound Forever: The Story of recorded Music, Granta Books, London, 2009 (ISBN 978-1-84708-140-7), p. 149

- ^ a b Skates, Sarah (June 30, 2011). "Quonset Hut Hosts Reunion Celebration". Music Row. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ "History of The Liederkranz of the City of New York" Archived July 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine – The Liederkranz of the City of New York website. The Liederkranz Club put up a building in 1881 at 111–119 East 58th Street, east of Park Avenue.

- ^ North, James H., New York Philharmonic: the authorized recordings, 1917–2005 : a discography, Rowman & Littlefield, 2006. Cf. especially p.xx

- ^ Behncke, Bernhard, "Leiderkranz Hall – The World's Best Recording Studio?", VJM's Jazz & Blues Mart magazine.

- ^ "Morty Palitz Dies at 53; Spanned 3 Record Decades", Billboard, December 1, 1962.

- ^ Kahn, Ashley, Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece, Da Capo Press, 2001. Cf. p.75

- Dannen, Frederic (1991). Hit Men: Power Brokers and Fast Money Inside The Music Business. London: Vintage. ISBN 0099813106.

Further reading

[edit]- Cogan, Jim; Clark, William, Temples of sound : inside the great recording studios, San Francisco : Chronicle Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8118-3394-1. Cf. chapter on Columbia Studios, pp. 181–192.

- Hoffmann, Frank, Encyclopedia of Recorded Sound, New York & London : Routledge, 1993 & 2005, Volume 1. Cf. pp. 209–213, article on "Columbia (Label)"

- Koenigsberg, Allen, The Patent History of the Phonograph, 1877–1912, APM Press, 1990/1991, ISBN 0-937612-10-3.

- Revolution in Sound: A Biography of the Recording Industry. Little, Brown and Company, 1974. ISBN 0-316-77333-6.

- High Fidelity Magazine, ABC, Inc. April 1976, "Creating the LP Record."

- Rust, Brian, (compiler), The Columbia Master Book Discography, Greenwood Press, 1999.

- Marmorstein, Gary. The Label: The Story of Columbia Records. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press; 2007. ISBN 1-56025-707-5

- Ramone, Phil; Granata, Charles L., Making records: the scenes behind the music, New York: Hyperion, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7868-6859-9. Many references to the Columbia Studios, especially when Ramone bought Studio A, 799 Seventh Avenue from Columbia. Cf. especially pp. 136–137.

- Dave Marsh; 360 Sound: The Columbia Records Story Legends and Legacy, Free eBook released by Columbia Records that puts a spotlight on the label's 263 greatest recordings from 1890 to 2011.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Columbia masters in the Discography of American Historical Recordings

- See the Profile of Designer Alex Steinweiss

- Columbia Records

- 1889 establishments in New York (state)

- American companies established in 1889

- American country music record labels

- American record labels

- Companies based in Manhattan

- Contemporary R&B record labels

- Cylinder record producers

- Entertainment companies based in New York City

- Hip hop record labels

- Jazz record labels

- Mass media companies of the United States

- Pop record labels

- Record labels established in 1889

- Rhythm and blues record labels

- Rock record labels

- Sony Music

- Soundtrack record labels