Heat (1995 film)

| Heat | |

|---|---|

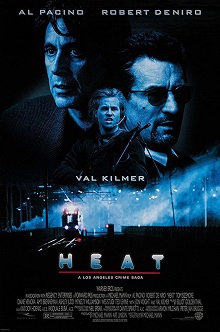

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Mann |

| Written by | Michael Mann |

| Based on | L.A. Takedown by Michael Mann |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dante Spinotti |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Elliot Goldenthal |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 170 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $60 million[1] |

| Box office | $187.4 million[2] |

Heat is a 1995 American crime film[3] written and directed by Michael Mann. It features an ensemble cast led by Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, with Tom Sizemore, Jon Voight, and Val Kilmer in supporting roles.[4] The film follows the conflict between an LAPD detective, played by Pacino, and a career thief, played by De Niro, while also depicting its effect on their professional relationships and personal lives.

Mann wrote the original script for Heat in 1979, basing it on Chicago police officer Chuck Adamson's pursuit of criminal Neil McCauley, after whom De Niro's character is named.[5] The script was first used for a television pilot developed by Mann, which became the 1989 television film L.A. Takedown after the pilot did not receive a series order. In 1994, Mann revisited the script to turn it into a feature film, co-producing the project with Art Linson. The film marks De Niro and Pacino's first on-screen appearance together following a period of acclaimed performances from both. Due to their esteemed reputations, promotion centered on their involvement.

Heat was released by Warner Bros. Pictures on December 15, 1995, to critical and commercial success. It grossed $187 million on a $60 million budget, while receiving positive reviews for Mann's direction and the performances of Pacino and De Niro. The film is regarded as one of the most influential films of its genre and has inspired several other works.[6][7][8] A sequel was announced to be in development on July 20, 2022.[9]

Plot

[edit]Neil McCauley is a professional thief based in Los Angeles. He and his crew – right-hand man Chris Shiherlis, enforcer Michael Cheritto, driver Gilbert Trejo, and newly hired hand Waingro – rob $1.6 million in bearer bonds from an armored car. During the heist, Waingro kills a guard without provocation, forcing the crew to eliminate the other two guards. Later, McCauley prepares to kill Waingro in retaliation for the deaths of the guards, but he escapes.

Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) Lieutenant Vincent Hanna and his team investigate the robbery. Hanna, a dedicated lawman and former Marine, has a strained relationship with his third wife Justine, and struggles to connect with his stepdaughter, Lauren. McCauley, who lives a solitary life, begins a relationship with Eady, a graphic designer. They bond over their mutual isolation from society, and, claiming to be a metalworker, McCauley asks her to emigrate to New Zealand with him.

McCauley's fence Nate suggests he sell the stolen bonds back to their original owner, money launderer Roger Van Zant. Van Zant pretends to agree but instead arranges an ambush. Anticipating a trap, McCauley and his crew counter-ambush and kill the hitmen. Afterwards, McCauley threatens Van Zant with revenge. An LAPD informant connects Cheritto to the robbery, and Hanna's team begins monitoring him, identifying the rest of the crew and their next target, a precious metals depository. The team stakes out the depository, but when a careless officer makes a noise, McCauley aborts the heist.

McCauley's crew agree to one last bank robbery worth $12.2 million. Hanna tracks McCauley and pulls him over on the 105 Freeway, inviting him to coffee. They discuss their dedication to their respective jobs and the limitations of their personal lives; Hanna describes his failing marriage and McCauley confides that he is similarly isolated. Despite their mutual respect, both acknowledge that they will kill the other if necessary. Waingro makes a deal with Van Zant to help eliminate McCauley's crew. Trejo quits the bank robbery at the last moment, claiming the LAPD is following him too closely. McCauley recruits an old colleague, Don Breedan, to take Trejo's place as the getaway driver, and the crew carries out the heist.

Tipped by Van Zant's bodyguard, the LAPD intercepts the crew as they leave the bank, leading to a massive shootout. Breedan and Cheritto are killed alongside 18 police officers, while McCauley escapes with a wounded Shiherlis, and Hanna loses two of his fellow detectives. McCauley takes Shiherlis to a doctor to treat his wounds and leaves him with Nate. Suspecting Trejo tipped off the LAPD, McCauley arrives at his house to confront him, but finds him mortally wounded and his wife killed. Trejo reveals Waingro and Van Zant forced him to divulge the bank heist plans before asking McCauley to kill him. McCauley breaks into Van Zant's mansion and kills him. Upon learning of McCauley's connection to Waingro and that the latter is hiding in a hotel, Hanna uses Waingro as bait to lure McCauley. As McCauley prepares to flee the country, Eady discovers his criminal identity, but agrees to go with him. Before escaping, Shiherlis attempts to reconcile with his wife Charlene, who has been forced by the LAPD to bring him in. As Shiherlis encounters Charlene at her safe house, she warns him away with a hand gesture, and he escapes.

Having separated from Justine, Hanna finds Lauren has attempted suicide in his own hotel room and rushes her to the hospital, saving her life; he reconciles with Justine, although they both agree that their relationship will never work.

McCauley drives to the Los Angeles International Airport with Eady to flee to New Zealand via private jet. However, when Nate gives him Waingro's location, McCauley abandons his usual caution to seek revenge. McCauley infiltrates the hotel and kills Waingro in his room. However, as McCauley returns to Eady, he is spotted by Hanna and flees. Hanna chases McCauley onto the tarmac at the airport, and the two stalk each other, before Hanna eventually gets the drop on McCauley and shoots him in the chest. Hanna takes McCauley's hand as he dies of his wounds.

Cast

[edit]- Al Pacino as Lieutenant Vincent Hanna

- Robert De Niro as Neil McCauley

- Val Kilmer as Chris Shiherlis

- Jon Voight as Nate

- Tom Sizemore as Michael Cheritto

- Diane Venora as Justine Hanna

- Amy Brenneman as Eady

- Ashley Judd as Charlene Shiherlis

- Mykelti Williamson as Sergeant Bobby Drucker

- Wes Studi as Detective Sammy Casals

- Ted Levine as Detective Mike Bosko

- Dennis Haysbert as Don Breedan

- William Fichtner as Roger Van Zant

- Natalie Portman as Lauren Gustafson

- Tom Noonan as Kelso

- Kevin Gage as Waingro

- Hank Azaria as Alan Marciano

- Danny Trejo as Gilbert Trejo[10]

- Susan Traylor as Elaine Cheritto

- Kim Staunton as Lillian

- Henry Rollins as Hugh Benny

- Jerry Trimble as Detective Danny Schwartz

- Tone Loc as Richard Torena

- Ricky Harris as Albert Torena

- Ray Buktenica as Timmons

- Jeremy Piven as Dr. Bob

- Xander Berkeley as Ralph

Additional cast members include Martin Ferrero as a hardware salesman and Hazelle Goodman as the mother of a prostitute murdered by Waingro. Featured as members of the LAPD are Paul Herman as Sergeant Heinz, Cindy Katz as forensics investigator Cindy, and Dan Martin as Detective Harry Dieter. Stuntmen Rick Avery, Bill McIntosh, and Thomas Rosales Jr. portray the armored truck guards. Patricia Healy appears as a woman in a relationship with Bosko and Yvonne Zima plays the girl taken hostage by Cheritto. News reporter Claudia is portrayed by Farrah Forke. Bud Cort makes an uncredited appearance as restaurant owner Solenko.[11]

Development

[edit]Factual basis

[edit]Heat is based on the true story of Neil McCauley, a calculating criminal and ex-Alcatraz inmate who was tracked down by Detective Chuck Adamson in 1964.[12][13] In 1961, McCauley was transferred from Alcatraz to McNeil Island Corrections Center, as mentioned in the film. He was released in 1962 and immediately began planning new crimes. Michael Parille and William Pinkerton used bolt cutters and drills to rob a manufacturing company of diamond drill bits, which is recreated in the film.[14] Pacino's character is largely based on Detective Chuck Adamson, who began keeping tabs on McCauley's crew, knowing that he had begun committing crimes again. Adamson and McCauley even met for coffee once, as portrayed in the film.[13] Their dialogue in the script was based on the conversation that McCauley and Adamson had.[14] The next time that the two met, guns were drawn, which is also mirrored in the movie.[13]

On March 25, 1964, McCauley and members of his regular crew followed an armored car that delivered money to a National Tea grocery store at 4720 S. Cicero Avenue, Chicago. Once the drop was made, three of the robbers entered the store. They threatened the clerks and stole money bags worth $13,137[15] (equivalent to $129,000 in 2023) before they sped off in a rainstorm amid police gunfire.[13][14]

McCauley's crew was unaware that Adamson and eight other detectives had blocked off all potential exits; the getaway car turned down an alley and the robbers saw the blockade and realized that they were trapped. All four exited the vehicle and began firing. Russell Bredon (or Breaden) and Michael Parille were slain in an alley while Miklos Polesti (on whom Chris Shiherlis is very loosely based)[13] shot his way out and escaped. McCauley was shot to death on the lawn of a nearby home. He was 50 years old and the prime suspect in several burglaries.[16] Polesti was caught days later and sent to prison. Polesti was still alive in 2011.[14]

Adamson went on to a successful career as a television and film producer, and he died in 2008 at age 71.[17] Mann's 2009 film Public Enemies is dedicated to Adamson's memory.

The character of Nate played by Jon Voight is based on criminal turned author Edward Bunker, who served as a consultant to Mann on the film.[13][14][18]

Canceled TV series

[edit]In 1979, Mann wrote a 180-page draft of Heat. He re-wrote it after making Thief in 1981 hoping to find a director to make it and mentioning it publicly in a promotional interview for his 1983 film The Keep. In the late 1980s, he offered the film to his friend, film director Walter Hill, who turned him down.[19] Following the success of Miami Vice and Crime Story, Mann was to produce a new crime television show for NBC. He turned the script that would become Heat into a 90-minute pilot for a television series featuring the Los Angeles Police Department Robbery–Homicide division,[19] featuring Scott Plank in the role of Hanna and Alex McArthur playing the character of Neil McCauley, renamed to Patrick McLaren.[20] The pilot was shot in only nineteen days, atypical for Mann.[19] The script was abridged down to almost a third of its original length, omitting many subplots that made it into Heat. The network was unhappy with Plank as the lead actor, and asked Mann to recast Hanna's role. Mann declined and the show was canceled and the pilot aired on August 27, 1989, as a television film entitled L.A. Takedown[19] which was later released on VHS and DVD in Europe.[21]

Production

[edit]Pre-production

[edit]On April 5, 1994, Mann was reported to have abandoned his earlier plan to shoot a biopic of James Dean in favor of directing Heat, producing it with Art Linson. The film was marketed as the first on-screen appearance of Al Pacino and Robert De Niro together in the same scene—both actors had previously starred in The Godfather Part II, but owing to the film's double story structure, they were never seen in the same scene.[22] Pacino and De Niro were Mann's first choices for the roles of Hanna and McCauley, respectively, and they both immediately agreed to act.[23]

Mann assigned Janice Polley, a former collaborator on The Last of the Mohicans, as the film's location manager, along with Lori Balton who primarily handled scouting duties. Scouting locations lasted from August to December 1994. Mann requested locations which had not appeared on film before, in which Balton was successful—fewer than 10 of the 85 filming locations were previously used. The most challenging shooting location proved to be Los Angeles International Airport, with the film crew almost missing out due to a threat to the airport by the Unabomber.[19] On the DVD commentary, Mann noted it would be impossible to film the airport climax in the same way following the events of 9/11.

To make the long shootout more realistic they hired British ex-Special Air Service sergeant Andy McNab as a technical weapons trainer and adviser.[24] He designed a weapons training curriculum to train the actors for three months using live ammunition before shooting with blanks for the actual take and worked with training them for the bank robbery.[25]

Casting

[edit]De Niro was the first cast member to receive the film script, showing it to Pacino, who also wanted to be a part of the film. De Niro believed that Heat was a "very good story, had a particular feel to it, a reality and authenticity."[19] In 2016, Pacino revealed that he viewed his character as having been under the influence of cocaine throughout the whole film.[26]

Mann took Kilmer, Sizemore, and De Niro to Folsom State Prison to interview actual career criminals to prepare for their roles. While researching her role, Judd met several former prostitutes who became housewives.[19]

Keanu Reeves was offered the role of Chris Shiherlis, but he turned it down in favor of playing Hamlet at the Manitoba Theatre Centre.[27] As a result, Val Kilmer was given the role.

Filming

[edit]Principal photography for Heat lasted 107 days during the summer of 1995.[28] All of the shooting was done on location, in and around Los Angeles, due to Mann's decision not to use a soundstage.[19] Among the key filming locations were the Citigroup Center, where the bank heist and police shootout took place, and the Kate Mantilini restaurant, which served as the location of the meeting over coffee between Pacino and De Niro's characters.

The film's cinematographer, Dante Spinotti, used a combination of natural and practical lighting to capture grittiness and realism for the film. The film's visual style also captured the vastness of Los Angeles and the isolation of its characters within the urban sprawl. Mann and Spinotti often used wide shots and long takes to create a sense of scale and immersion.[29]

Both Al Pacino and Robert De Niro prepared extensively for their roles. They spent time with real detectives and criminals to understand their characters in depth. The diner scene between Pacino and De Niro was shot with minimal rehearsals to maintain the spontaneity and intensity of their interaction. Mann used multiple cameras to capture the scene from different angles, focusing on close-ups to highlight the tension and subtleties of each actor's performance.[30][29]

Post-production

[edit]Sound design

[edit]Heat is recognized for its realistic sound design, particularly during the iconic bank heist scene. Real gunfire sounds were used to capture the intensity and chaos of the shootout. The sound design plays a significant role in immersing the audience in the action, making the sequences feel immediate and visceral.[29]

Editing

[edit]The editing of Heat focuses on maintaining its narrative pace and tension. Editor Dov Hoenig worked closely with Mann to ensure that each scene flowed naturally and kept the audience engaged. The film's editing balanced intense action sequences with quieter, character-driven moments, which is noted for creating a dynamic and compelling viewing experience.[29]

Soundtrack

[edit]On December 19, 1995, Warner Bros. Records released a soundtrack album on cassette and CD to accompany the film, entitled Heat: Music from the Motion Picture.[31] The album was produced by Matthias Gohl. It contains a 29-minute selection of the film score composed by Elliot Goldenthal, as well as songs by other artists such as U2 and Brian Eno (collaborating as Passengers), Terje Rypdal, Moby, and Lisa Gerrard. Heat used an abridged instrumental rendition of the Joy Division song "New Dawn Fades" by Moby, which also features in the same form on the soundtrack album. Mann reused the Einstürzende Neubauten track "Armenia" in his 1999 film The Insider.[32] The film ends with Moby's "God Moving Over the Face of the Waters", a different version of which was included at the end of the soundtrack album.[33]

Mann and Goldenthal decided on an atmospheric situation for the film soundtrack. Goldenthal used a setup consisting of multiple guitars, which he termed "guitar orchestra", and thought it brought the film score closer to a European style.[34]

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]Heat was released on December 15, 1995, and opened at the box office with $8.4 million from 1,325 theaters, finishing in third place behind Jumanji and Toy Story.[35][36] It went on to earn a total gross of $67.4 million in United States box offices, and $120 million in foreign box offices.[37] Heat was ranked the #25 highest-grossing film of 1995.[37]

Home media

[edit]Heat was released on VHS on November 12, 1996, by Warner Home Video.[38][39] Due to its running time, the film had to be released on two cassettes.[39] A DVD release followed on July 27, 1999.[40] A two-disc special-edition DVD was released by Warner Home Video on February 22, 2005, featuring an audio commentary by Michael Mann, deleted scenes, and numerous documentaries detailing the film's production.[41] This edition contains the original theatrical cut.[42]

The initial Blu-ray Disc was released by Warner Home Video on November 10, 2009, featuring a high-definition film transfer, supervised by Mann.[43] Among the disc extras were Mann's audio commentary, a one-hour documentary about the making of the film and ten minutes worth of scenes cut from the film.[44] As well as approving the look of the transfer, Mann also recut two scenes slightly differently, referring to them as "new content changes".[45]

A Director's Definitive Edition Blu-ray was released on May 9, 2017, by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, who acquired the distribution rights to the film through their part-ownership of Regency back in 2015. Sourced from a 4K remaster of the film supervised by Mann, the two-disc set contains all the extras from the 2009 Blu-ray, along with two filmmakers panels from 2015 and 2016, one of which was moderated by Christopher Nolan.[46] A 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Ultimate Collector's Edition of Heat that contains the Director's Definitive Edition of the film on UHD Blu-ray and Blu-ray along with legacy bonus materials was released on August 9, 2022, by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment (under the 20th Century Studios label), coinciding with the release date of Mann's sequel novel.[47] Unlike the previous home media releases, the Director's Definitive Edition Blu-ray and the 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Ultimate Collector's Edition did not feature the Warner Bros. Pictures logo at the beginning, although the in-credit closing is retained.

Heat was broadcast on NBC television on January 3, 1999, in a significantly edited version. Mann had offered the network scenes which had been filmed but omitted from the theatrical edit in hopes of having the film shown in four hours (with commercials) over two nights. Instead, NBC chose to cut nearly 40 minutes from the theatrical version so that Heat could be shown in a three-hour time slot (with commercials). Mann told Variety, "They cut so much out of the movie that they destroyed the narrative of the film along with its integrity.... Too much time was taken out of the film that wasn't due to language or other content." As a result, Mann had his director's credit on the TV version replaced with the pseudonym "Alan Smithee".[48]

Reception

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes, Heat holds an approval rating of 83% based on 151 reviews and an average rating of 7.8/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Though Al Pacino and Robert De Niro share but a handful of screen minutes together, Heat is an engrossing crime drama that draws compelling performances from its stars – and confirms Michael Mann's mastery of the genre."[3] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 76 out of 100, based on 22 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[49] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[50]

Roger Ebert gave the film three and a half stars out of four. He described Mann's script as "uncommonly literate", with a psychological insight into the symbiotic relationship between police and criminals, and the fractured intimacy between the male and female characters: "It's not just an action picture. Above all, the dialogue is complex enough to allow the characters to say what they're thinking: They are eloquent, insightful, fanciful, poetic when necessary. They're not trapped with cliches. Of the many imprisonments possible in our world, one of the worst must be to be inarticulate – to be unable to tell another person what you really feel."[51] Simon Cote of The Austin Chronicle called the film "one of the most intelligent crime-thrillers to come along in years", and said Pacino and De Niro's scenes together were "poignant and gripping."[52]

Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times called the film a "sleek, accomplished piece of work, meticulously controlled and completely involving. The dark end of the street doesn't get much more inviting than this."[53] Todd McCarthy of Variety wrote, "Stunningly made and incisively acted by a large and terrific cast, Michael Mann's ambitious study of the relativity of good and evil stands apart from other films of its type by virtue of its extraordinarily rich characterizations and its thoughtful, deeply melancholy take on modern life."[4] Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly gave it a B− rating, saying that "Mann's action scenes ... have an existential, you-are-there jitteriness," but called the heist-planning and Hanna's investigation scenes "dry, talky."[54]

Rolling Stone ranked Heat #28 on its list of "The 100 Greatest Movies of the '90s",[55] and The Guardian ranked it #22 on its list of "The Greatest Crime Films of All Time",[56] while other publications have noted its influence on numerous subsequent films.[57]

Although it did not receive any major award nominations, the film was nominated for Best Action/Adventure Film and Kilmer for Best Supporting Actor at the Saturn Awards but lost to The Usual Suspects and 12 Monkeys respectively.[58]

Impact

[edit]French gangster Rédoine Faïd told Mann at a film festival "You were my technical adviser".[59] The media described later robberies as resembling scenes from Heat, including armored car robberies in South Africa,[60] Colombia,[61] Denmark, and Norway[62] and the 1997 North Hollywood shootout, in which Larry Phillips Jr. and Emil Mătăsăreanu robbed the North Hollywood branch of the Bank of America and, similarly to the film, were confronted by the LAPD as they left the bank. A copy of "Heat" was found in the VCR at Phillips' residence.[63] This shootout is considered one of the longest and bloodiest events of its type in American police history. Both robbers were killed, and eleven police officers and seven civilians were injured during the shootout.[64] Heat was widely referenced during the coverage of the shootout.[65]

For his 2008 film The Dark Knight, director Christopher Nolan drew inspiration in his portrayal of Gotham City from Heat in order "to tell a very large, city story or the story of a city".[66] In 2016, a year after the 20th anniversary of Heat, Nolan moderated a Q&A session with Michael Mann and cast and crew at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater.[67]

Heat was one of the inspirations behind the highly influential 2001 video game Grand Theft Auto III[68] as well as the 2008 sequel Grand Theft Auto IV, notably the mission "Three Leaf Clover", which was inspired by the climactic bank robbery and police shootout,[69] and the 2013 sequel Grand Theft Auto V, notably the mission "Blitz Play" where the crew blocks and then knocks over an armored car in order to rob it.[70]

Director Mia Hansen-Løve has said she is "obsessed" with Heat and said "the themes of Heat, actually, are themes of my films, except in a very different way, in a very different world".[71]

Subsequent works

[edit]On March 16, 2016, Mann announced that he was developing a Heat prequel novel, as a part of launching his company Michael Mann Books.[72] On April 27, 2017, Reed Farrel Coleman joined the project as co-author.[73] On May 15, 2020, Mann stated that the novel would function as both a prequel and a sequel, with plot taking place before and after the film's main events.[74] By January 19, 2022, it was revealed that the novel would be a collaboration between Mann and Meg Gardiner; it was subsequently released in August 2022. The title is Heat 2.[75][76]

In September 2019, Michael Mann stated that he intends to produce an adaptation of the novel, acknowledging film and television as possible mediums for release.[77] By July 5, 2022, Mann reaffirmed his plans to adapt the novel follow-up into a feature film, while stating that the principal cast from the first installment may be recast for the adaptation.[78] In April 2023, it was reported that the sequel was in development, with Adam Driver in talks to play young McCauley.[79][80]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Heat (1995)". JP's Box-Office (in French). Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ^ "Heat (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Heat (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved December 20, 2023.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Todd (December 5, 1995). "Review: Heat". Variety. Retrieved March 27, 2014.

- ^ George M. Thomas (February 27, 2005). "He's a Goofy Goober; 'Heat'". Akron Beacon Journal.

- ^ Rivers, Marc (September 5, 2020). "Michael Mann's 'Heat' At 25: A Newly Relevant Study In Loneliness". NPR. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ^ Valero, Gerardo (September 7, 2020). "Why Heat is the Greatest Heist Movie Ever Made". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ^ Mosley, Matthew (January 7, 2024). "The Immense Scope of Michael Mann's 'Heat' Remains Unmatched". Collider. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ^ Leston, Ryan (July 20, 2022). "Michael Mann's Heat 2 'Already Underway'". IGN. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ "Danny Trejo Breaks Down His Most Iconic Characters | GQ". YouTube. December 23, 2022. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ Godfrey, Alex (July 10, 2014). "Bud Cort: 'Harold and Maude was a blessing and a curse'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ Wael Khairy (December 14, 2012). "Crime in the emptiness of Los Angeles". rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Rybin, Steven (2007). The Cinema of Michael Mann. Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739153031. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e DVD Extra Interview with Michael Mann; The Making of Heat

- ^ "Heroes Commended by Wilson; Warns Gangs: Flee or be Killed". Chicago Tribune. March 27, 1965. p. 2. Retrieved November 25, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "We've got them all!!!". scrappygraphics.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ "Adamson, Chuck". Las Vegas Review-Journal. March 2, 2008. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ "Edward Bunker". Telegraph.co.uk. July 26, 2005. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lafrance, J.D. (November 19, 2010). "Heat". Radiator Heaven. Archived from the original on May 12, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- ^ Mann, Michael (director, writer) (August 27, 1989). L.A. Takedown (Television film). NBC.

- ^ Mann, Michael (director, writer) (March 19, 2008). L.A. Takedown (DVD). Concorde Video.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (April 5, 1994). "Mann prepping De Niro-Pacino pic". Variety. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ Mann, Michael (Director) (February 22, 2005). The Making of 'Heat' (DVD, part of Heat – Two-Disc Special Edition). Warner Home Video.

- ^ Klimek, Chris (January 15, 2015). "The long warm-up to Heat". The Dissolve. Archived from the original on July 27, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2015.

- ^ Heat Shootout Behind the Scenes Feature. YouTube. October 8, 2009. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021.

- ^ Stolworthy, Jacob (September 8, 2016). "Christopher Nolan interviewed Robert De Niro and Al Pacino about Heat". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved October 7, 2016.

- ^ "Keanu Reeves: 'I felt like I was fighting for my life'". The Telegraph. April 3, 2015.

- ^ Hersey, Will (December 27, 2020). "'Heat' at 25: The Making of a Modern Classic". Esquire. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Michael Mann's 'Heat': A Complex, Stylistically Supreme Candidate for One of the Most Impressive Films of the Nineties • Cinephilia & Beyond". March 9, 2016. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Heat movie review & film summary (1995) | Roger Ebert". www.rogerebert.com/. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ McDonald, Steven. "Heat: Music from the Motion Picture - Original Soundtrack". AllMusic. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Lisa Gerrard – The Insider". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Clemmensen, Christian (August 11, 2003). "Heat". Filmtracks.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Goldwasser, Dan (January 2000). "The Sweet Revenge of Elliot Goldenthal". Soundtrack.Net. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ "'Toy Story,' 'Jumanji' duel for box office lead". The Sheboygan Press. December 19, 1995. p. 19. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for December 15-17, 1995". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ a b "Heat (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ^ Tuckman, Jeff (June 21, 1996). "Pacino and De Niro shoot up the screen in explosive 'Heat' On video". Daily Herald. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ^ a b Nichols, Peter M. (April 19, 1996). "Home Video". The New York Times. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ^ Mann, Michael (director) (November 1, 1999). Heat (DVD). Warner Home Video.

- ^ "BBC - Movies - review - Collateral: Collector's Edition DVD". BBC. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- ^ "'Heat' Rewind DVD comparison". dvdcompare.net. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "Heat Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. November 10, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Kenneth, Brown (November 4, 2009). "Heat Blu-ray Review". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ "'Heat' Home Theater Forum Blu-ray review".

- ^ "Heat Director's Definitive Blu-ray Edition Detailed". blu-ray.com. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Heat (1995) 4k Blu-ray & 4k SteelBook Release Dates Finally Confirmed". Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "Mann bites Peacock; just the facts for Permut". Variety.com. January 4, 1999. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ "Heat (1995): Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ "cinemascore.com". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on January 2, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ "Heat :: Reviews". RogerEbert.com. December 15, 1995. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ "Heat". The Austin Chronicle. September 22, 1997. Archived from the original on August 30, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ "Critic Reviews for Heat". Metacritic. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (December 22, 1995). "Heat Review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ Editorial staff (July 12, 2017). "The 100 Greatest Movies of the Nineties". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ "Heat: No 22 best crime film of all time". The Guardian. October 17, 2010. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ Goodman, William (December 15, 2020). "The Action Is the Juice: Ranking the Heat Homages". GQ. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- ^ "1995 – 22nd Saturn Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ "Redoine Faid: Paris helicopter prison break for gangster" Archived July 19, 2024, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, July 1, 2018

- ^ "Just Blame The Heat". Free.financialmail.co.za. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ McDermott, Jeremy (August 5, 2003). "Life imitates art in Colombia robbery". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ "The big coup". Translate.google.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ^ "North Hollywood Shootout: Baptism of Fire". Police Magazine. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ^ Rogers, Kenneth (2013). "Capital Implications: the Function of Labor in the Video Art of Juan Devis and Yoshua Okon". Digital Media, Cultural Production and Speculative Capitalism. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 9781317982319.

- ^ James, Nick (2002). Heat. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 74–76. ISBN 9780851709383.

- ^ Stax (December 6, 2007). "IGN interviews Christopher Nolan". IGN Movies. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ Tapley, Kristopher (September 7, 2016). "Christopher Nolan Talks Michael Mann's 'Heat' With Cast and Crew at the Academy". Variety. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ Kushner, David (April 3, 2012). Jacked: The Outlaw Story of Grand Theft Auto. Turner Publishing Company. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-4709-3637-5.

- ^ "GTA Missions Don't Get Much Better Than Three Leaf Clover". November 22, 2021. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Petit, Carolyn (October 8, 2013). "Taking Scores: Heat and Grand Theft Auto V". GameSpot. Archived from the original on September 7, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2016.

- ^ Newman, Nick (November 30, 2016). "Mia Hansen-Løve on Abbas Kiarostami, Her Obsession With 'Heat,' and the Meaning of 'Things to Come'". thefilmstage.com. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (March 16, 2016). "Michael Mann Launches Book Imprint; 'Heat' Prequel Novel A Priority". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ^ "Michael Mann Sets Bestselling Author Reed Farrel Coleman to Co-Write 'Heat' Prequel Novel". Deadline. April 27, 2017. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved January 20, 2022.

- ^ "Michael Mann Wants to Turn His 'Heat' Prequel Novel Into a Movie, And Make a Sequel, Too". /Film. May 15, 2020. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 19, 2022). "'Heat' Fans Rejoice: Michael Mann & Meg Gardiner Novel 'Heat 2' Has August 9 Pub Date And Will Detail Lives Of Characters Before & After 1995 Crime Classic". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved January 19, 2022.

- ^ "Review of Heat 2 novel". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Michael Mann says 'Heat 2' sequel is on the cards". Esquire Middle East – the Region's Best Men's Magazine. September 2019. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Travis, Ben (July 5, 2022). "Michael Mann Wants To Make Heat 2 As A Movie – Exclusive". Esquire. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (April 3, 2023). "Michael Mann Eyeing Heat 2 As Next Film With Warner Bros In Negotiations With Director To Board Sequel; Adam Driver In Talks With Mann To Play Young Neil McCauley". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on May 20, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ "Michael Mann Confirms 'Heat 2' As Next Movie & Comments On Potential Reteam With Adam Driver". deadline. October 9, 2023. Archived from the original on July 19, 2024. Retrieved October 10, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Heat at IMDb

- Heat at AllMovie

- Heat at Box Office Mojo

- Heat at Rotten Tomatoes

- Heat at Metacritic

- Heat. Work and genre Jump Cut magazine, by J. A. Lindstrom, no. 43, July 2000, pp. 21–37

- De Niro and Pacino Star in a Film. Together, from The New York Times

- 1995 films

- 1995 action films

- 1995 crime drama films

- 1990s heist films

- 1990s police films

- American crime drama films

- American gangster films

- American heist films

- American neo-noir films

- American police detective films

- Films about the Los Angeles Police Department

- Films about bank robbery

- Films about organized crime in the United States

- Films directed by Michael Mann

- Films produced by Art Linson

- Films produced by Michael Mann

- Films scored by Elliot Goldenthal

- Films set in Koreatown, Los Angeles

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films shot in California

- Films with screenplays by Michael Mann

- Regency Enterprises films

- Warner Bros. films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s American films

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- English-language crime drama films