Eppa Rixey

| Eppa Rixey | |

|---|---|

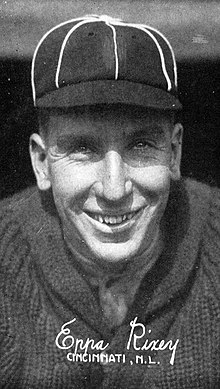

Rixey, c. 1922 | |

| Pitcher | |

| Born: May 3, 1891 Culpeper, Virginia, U.S. | |

| Died: February 28, 1963 (aged 71) Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Left | |

| MLB debut | |

| June 21, 1912, for the Philadelphia Phillies | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 5, 1933, for the Cincinnati Reds | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 266–251 |

| Earned run average | 3.15 |

| Strikeouts | 1,350 |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1963 |

| Election method | Veterans Committee |

Eppa Rixey Jr. (May 3, 1891 – February 28, 1963), nicknamed "Jephtha",[A] was an American baseball player who played 21 seasons for the Philadelphia Phillies and Cincinnati Reds in Major League Baseball from 1912 to 1933 as a left-handed pitcher. Rixey was best known as the National League's leader in career victories for a left-hander with 266 wins until Warren Spahn surpassed his total in 1959.

Rixey attended the University of Virginia where he was a star pitcher. He was discovered by umpire Cy Rigler, who convinced him to sign directly with the Phillies, bypassing minor league baseball entirely. His time with the Phillies was marked by inconsistency. He won 22 games in 1916, but also led the league in losses twice. In 1915, the Phillies played in the World Series, and Rixey lost in his only appearance.[1] After being traded to the Reds prior to the 1921 season, he won 20 or more games in a season three times, including a league-leading 25 in 1922, and posted eight consecutive winning seasons. His skills were declining by the 1929 season, when his record was 10–13 with a 4.16 earned run average. He pitched another four seasons before retiring after the 1933 season.

An intellectual who taught high school Latin during the off-season, earning the nickname "Jephtha" for his southern drawl, Rixey was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1963.

Early life

[edit]Eppa Rixey Jr. was born on May 3, 1891, in Culpeper, Virginia, to Eppa Rixey and his wife Willie Alice (née Walton). At the age of ten, his father, a banker, moved his family to Charlottesville, Virginia.[2] His uncles were John Franklin Rixey, a former congressman, and Presley Marion Rixey, a former Surgeon General of the United States Navy.[3] He attended the University of Virginia, where he played basketball and baseball; he was a member of Delta Tau Delta International Fraternity.[4] His brother Bill also played baseball for Virginia.[2][5] During the off-season, umpire Cy Rigler worked as an assistant coach for the University. He recognized Rixey's talent and tried to sign him to the Philadelphia Phillies.[2] Rixey originally declined, saying he wanted to be a chemist, but Rigler insisted, even offering a substantial portion of the bonus he received for signing a player.[2] With his family in financial trouble, Rixey accepted the deal. The National League, upon hearing of the deal, created a rule that prohibits umpires from signing players.[2] Neither Rixey nor Rigler received any signing bonus.[2]

Baseball career

[edit]Philadelphia Phillies

[edit]

Rixey joined the Phillies for the 1912 season without playing a single game of minor league baseball.[6] His time with the Phillies was marked by inconsistency. He went 10-10 in his first year, with a 2.50 earned run average (ERA) and 10 complete games in 23 games pitched.[7] He had a three hit shutout against the Chicago Cubs on July 18.[8] Rixey was on the losing end of a no-hitter by Jeff Tesreau on September 6.[9] After the season, the Chicago Cubs, under new manager Johnny Evers, offered a "huge sum" to the Phillies for Rixey, but manager Red Dooin declined the offer.[10] Prior to the 1913 season, Rixey notified the Phillies of his desire to finish his studies at the University of Virginia and graduate in June; however, after some negotiation, he decided to sign a contract and re-joined the team shortly after the season began.[11] That season, he appeared in 35 games, started 19 of them, winning nine games, and had a 3.12 earned run average. In 1914, his record worsened to 2–11, and his earned run average increased to 4.37.[7] Rixey's record improved to 11–12 in 1915, and his earned run average was 2.39 as the Phillies won the National League pennant and played the Boston Red Sox in the 1915 World Series. During Game 5 of the series, Rixey replaced starter Erskine Mayer for the final six innings of the game. He allowed three runs in the final two innings and lost 5–4.[12]

Rixey went 22–10 in 1916 with a 1.85 ERA and a career high of 134 strikeouts.[7] On June 29, Rixey pitched a four-hit shutout against the New York Giants, facing the minimum 27 batters, because of three double plays, and a player caught stealing.[13] In 1917, despite having a 2.27 earned run average, Rixey led the league in pitching losses with 21.[7] He also handled 108 chances without a single error.[7] Rixey hated losing and was known for destroying the team locker room, or disappearing for days at a time after a loss.[2] He missed the 1918 season to serve in the Chemical Warfare Division of the United States army during the war effort.[2] He struggled upon returning to baseball, going 6–12 with a 3.97 earned run average in 1919, and again leading the league in losses with 22 in 1920.[7] Prior to the 1920 season, rumours circulated that his former manager, Pat Moran, now with the Cincinnati Reds, was interested in trading for Rixey. The relationship between Rixey and manager Gavvy Cravath was never good, and Cravath had made known his desire to trade him; however, he stayed with the Phillies that season, working on his delivery with former pitcher Jesse Tannehill, who, Rixey admitted, helped with his pitching delivery.[14][15] On November 22, 1920, Rixey was traded to the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for Jimmy Ring and Greasy Neale.[7] His record during his eight seasons with the Phillies was 87 wins and 103 losses.[16]

Cincinnati Reds

[edit]

In his first season with the Reds, Rixey won 19 games, and set a Major League record by allowing just one home run in 301 innings pitched.[2] In three of the next four seasons, he had 20 or more victories each season, with a league-leading total of 25 in 1922.[7] He also led the league in innings pitched and hits allowed in 1922 and shutouts with four in 1924.[7] In 1926 he had 14 wins, followed by seasons of 12, 19 and 10 wins.[7] Rixey's production began to decline in 1930, when he went 9–13 with a 5.10 ERA, and pitched fewer than 200 innings for the first time since 1919. From 1931 through 1933, Rixey pitched very little, and was used almost exclusively against the Pittsburgh Pirates.[17] For the 1933 season, he was the only Reds pitcher with a winning record, at 6–3 as the Reds finished last in the National League at 58–94.[18] He retired prior to the 1934 season, stating "the manager wasn't giving me enough work".[17] Rixey completed his career with 266 wins, 251 losses, and a 3.15 ERA. He appeared in 692 games and completed 290, and had 20 wins and 14 saves as a relief pitcher.[7][16]

Rixey was a better than average hitting pitcher, posting a .191 batting average (291-for-1,522) with 95 runs, 33 doubles, 3 home runs, 111 RBI and 49 bases on balls. He was also better than average defensively, recording a .978 fielding percentage which was 20 points higher than the league average at his position.[7]

Bubbles Hargrave, former Cincinnati catcher, gave this testimonial: "Eppa was just great. He was great as a pitcher, fielder and competitor. I look on him as the most outstanding player I came in contact with in my entire career."[1] For his part, Rixey described his approach to the game in 1927 as follows: "How dumb can the hitters in this league get? I've been doing this for fifteen years. When they're batting with the count two balls and no strikes, or three and one, they're always looking for the fastball and they never get it."[19]

Legacy

[edit]Originally Rixey had trouble controlling his speed, but eventually, weighing in at 210 pounds, he became one of the most feared pitchers in baseball.[18] Rixey was considered a pitcher with a "peculiar motion," who rarely walked a batter.[17] Throughout his long career, Rixey charmed teammates and fans with his dry wit and big Southern drawl. His nonsensical nickname "Jephtha" seemed to capture his roots and amiable personality.[16] Some writers thought "Jephtha" was a part of Rixey's real name, but it was likely invented by a Philadelphia sportswriter.[16] Rob Neyer called Rixey the fourth best pitcher in Reds history behind Bucky Walters, Paul Derringer and teammate Dolf Luque.[20]

His 266 career victories stood as the record for most wins by a left-handed pitcher in the National League until Warren Spahn broke it in 1959; however, his 251 losses are an all-time record for left-handed pitchers.[2] He also held the record for most seasons pitched by a National League left-hander until Steve Carlton broke it in 1986.[16] As time passed, support for Rixey to be inducted to the Baseball Hall of Fame grew. He was inducted into the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame in 1958.[6][21] In 1960, Rixey finished third in the balloting behind former teammate Edd Roush and Sam Rice (who was later inducted the same year as Rixey).[22] Upon his election to the Hall of Fame on January 27, 1963, he was quoted as saying "They're really scraping the bottom of the barrel, aren't they?"[2]

In 1969, he was named by Reds fans as the greatest left-handed pitcher in Reds history.[23] The Reds Hall of Fame declared Rixey "was the best left-hander ever to pitch for the Reds with a 179–148 record, 180 complete games, 23 shutouts and a 3.33 ERA in his 13 seasons."[21]

In 1972 he was inducted into the first class of the Virginia Sports Hall of Fame and Museum.[24]

In 2017 he was inducted into the inaugural class of the University of Virginia Baseball Hall of Fame:[25]

Rixey's childhood home in Culpeper still stands, although it suffered some damage in the 2011 Virginia earthquake.[26]

Personal life

[edit]Rixey was married to Dorothy Meyers of Cincinnati and had two children, Eppa Rixey III and Ann Rixey Sikes; and five grandchildren, James Rixey, Eppa Rixey IV, Steve Sikes, Paige Sikes, and David Sikes.[16] After his retirement from baseball, Rixey worked for his father-in-law's successful insurance company in Cincinnati, eventually becoming president of the company.[16][27] He died of a heart attack on February 28, 1963, one month after his election to the Hall of Fame, becoming the first player to die between election and induction to the Hall of Fame.[2] He is interred at Greenlawn Cemetery in Milford, Ohio.[7][19]

When Rixey started playing, he was considered an "anomaly." He came from a well-off family and was college-educated, something that was rare during his era. He wrote poetry, and earned masters degrees in chemistry and Latin.[2] During the off-season, he was a Latin teacher at Episcopal High School in Alexandria, Virginia.[2] He was also considered among the best golfers among athletes during the time period.[6] Nonetheless, he was the target of hazing in his first few years in the major leagues. Eventually he teamed up with other college graduates Joe Oeschger and Stan Baumgartner and the hazing lessened to a degree.[2]

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Collectors Universe Staff (April 13, 2004). "Signing Habits and Autograph Analysis of Hall of Fame Pitcher Eppa Jeptha Rixey, Jr". Professional Sports Authentication (PSA/DNA). Archived from the original on March 30, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Eppa Rixey at the SABR Baseball Biography Project , by Jan Finkel, Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Fleitz, David L (2004). Ghosts in the gallery at Cooperstown : sixteen little-known members of the Hall of Fame. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland and Company. p. 138. ISBN 0-7864-1749-8.

- ^ "Famous Delts". Delta Tau Delta. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ "Yale Blanks Virginia" (PDF). The New York Times. Associated Press. April 23, 1916. p. B2. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Hall of Famer Eppa Rixey Dies". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. March 1, 1963. p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Eppa Rixey". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ "Virginia Pitcher Blanks Cubs" (PDF). The New York Times. Associated Press. July 20, 1912. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ "Phillies Get No Hit or Run From Tesreau". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 7, 1912. p. 7.

- ^ "Cincinnati Club blocks Chance Deal". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 19, 1912. p. 13.

- ^ "Rixey Signs Contract". The Pittsburgh Press. Associated Press. April 19, 1913. p. 6.

- ^ "1915 World Series". Baseball-Reference.com. Archived from the original on October 15, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ "Curtains Fails To Scare Giants Jinx". The New York Times. Associated Press. June 30, 1916. p. 12.

- ^ "Ex Chairman Garry as Happy as a Boy". The Sporting News. February 19, 1920. p. 2.

- ^ "Cravath Far From Blue at Prospects". The Sporting News. March 25, 1920. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g Porter, David L. (2000). Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Q-Z. Westport, Conn: Brassy's Inc/Greenwood Press. pp. 1294–1295. ISBN 0-313-31176-5.

- ^ a b c "Rice, Flick, Rixey, Clarkson Hall is Enlarged". St. Petersburg Evening Independent. Associated Press. January 28, 1963. p. 6.

- ^ a b "Veteran Eppa Rixey Quits Baseball". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. Associated Press. February 17, 1934. p. 15.

- ^ a b "Eppa Rixey Stats". Baseball Almanac. Archived from the original on October 20, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ Rob Neyer (2003). Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Lineups. New York: Fireside. p. 62. ISBN 0-7432-4174-6.

- ^ a b "Class of 1959: Eppa Rixey". Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ "No Hall of Fame Selection Made". Tri City Herald. Associated Press. February 4, 1960. p. 2.

- ^ Eppa Rixey at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- ^ "Eppa Rixey, Class of 1972". Virginia Sports Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ "Virginia Announces Inaugural Baseball Hall of Fame Class". Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ "EARTHQUAKE IN CULPEPER: The damage done" from the Culpeper Star Experiment

- ^ Fleitz, p. 137

Further reading

[edit]- Eppa Rixey Files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

- Hoie, Bob; Bauer, Carlos (1998). The Historical Register: The Complete Major & Minor League Record of Baseball's Greatest Players. San Diego and San Marino: Baseball Press Books.

- Ritter, Lawrence S. (March 19, 1992). The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It. New York: Macmillan & Co.Harper Perennial. pp. 384 Publisher: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-688-11273-0. ISBN 978-0-688-11273-8

- Thorn, John; Palmer, Pete; Gershman, Michael, eds. (2001). Total Baseball (7th ed.). Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing. ISBN 1-892129-03-5.

External links

[edit]- Eppa Rixey at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Eppa Rixey at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Eppa Rixey at Find a Grave

- 1891 births

- 1963 deaths

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Major League Baseball pitchers

- Philadelphia Phillies players

- Cincinnati Reds players

- National League (baseball) wins champions

- Virginia Cavaliers men's basketball players

- Virginia Cavaliers baseball players

- Baseball players from Virginia

- People from Culpeper, Virginia

- Baseball players from Cincinnati

- American men's basketball players