War of the Bavarian Succession

| War of the Bavarian Succession | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Austro-Prussian rivalry | |||||||||

Friedrich der Grosse und der Feldscher, Bernhard Rode | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 180,000–190,000[1] | 160,000[1] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| ~10,000 killed, wounded, captured, missing, sick or dead from disease[1] | ~10,000 killed, wounded, captured, missing, sick or dead from disease[1] | ||||||||

The War of the Bavarian Succession (German: Bayerischer Erbfolgekrieg; 3 July 1778 – 13 May 1779) was a dispute between the Austrian Habsburg monarchy and an alliance of Saxony and Prussia over succession to the Electorate of Bavaria after the extinction of the Bavarian branch of the House of Wittelsbach. The Habsburgs sought to acquire Bavaria, and the alliance opposed them, favoring another branch of the Wittelsbachs. Both sides mobilized large armies, but the only fighting in the war was a few minor skirmishes. However, thousands of soldiers died from disease and starvation, earning the conflict the name Kartoffelkrieg (Potato War) in Prussia and Saxony; in Habsburg Austria, it was sometimes called the Zwetschgenrummel (Plum Fuss).

On 30 December 1777, Maximilian III Joseph, the last of the junior Wittelsbach line, died of smallpox, leaving no children. Charles Theodore, a scion of a senior branch of the House of Wittelsbach, held the closest claim of kinship, but he also had no legitimate children to succeed him. His cousin, Charles II August, Duke of Zweibrücken, therefore had a legitimate legal claim as Charles Theodore's heir presumptive. Across Bavaria's southern border, Emperor Joseph II coveted the Bavarian territory and had married Maximilian Joseph's sister Maria Josepha in 1765 to strengthen any claim he could extend. His agreement with the heir, Charles Theodore, to partition the territory neglected any claims of the heir presumptive, Charles August.

Acquiring territory in the German-speaking states was an essential part of Joseph's policy to expand his family's influence in Central Europe. For King Frederick the Great of Prussia, Joseph's claim threatened Prussian influence in German politics, but he questioned whether he should preserve the status quo through war, diplomacy, or trade. Empress Maria Theresa, Joseph's mother and co-ruler, considered any conflict over the Bavarian electorate not worth bloodshed, and neither she nor Frederick saw any point in pursuing hostilities. Joseph would not drop his claim despite his mother's contrary insistence. Elector Frederick August III of Saxony wanted to preserve the territorial integrity of Bavaria for his brother-in-law, Charles August, and had no interest in seeing the Habsburgs acquire additional territory on his southern and western borders. Despite his dislike of Prussia, which had been Saxony's enemy in two previous wars, Charles August sought the support of Frederick, who was happy to challenge the Habsburgs. France became involved to maintain the balance of power. Finally, Empress Catherine the Great of Russia's threat to intervene on the side of Prussia with fifty thousand Russian troops forced Joseph to reconsider his position. With Catherine's assistance, he and Frederick negotiated a solution to the problem of the Bavarian succession with the Treaty of Teschen, signed on 13 May 1779.

For some historians, the War of the Bavarian Succession was the last of the old-style cabinet wars of the Ancien Régime era, in which troops maneuvered while diplomats traveled between capitals to resolve their monarchs' complaints. The subsequent French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars differed in scope, strategy, organization, and tactics.

Background

[edit]In 1713, Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI established a line of succession that gave precedence to his own daughters over the daughters of his deceased older brother, Emperor Joseph I. To protect the Habsburg inheritance, he coerced, cajoled, and persuaded the crowned heads of Europe to accept the Pragmatic Sanction. In this agreement, they acknowledged any of his legitimate daughters as the rightful queen of Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia, and archduchess of Austria—a break from the tradition of agnatic primogeniture.[2]

Holy Roman emperors had been elected from the House of Habsburg for most of the previous three centuries. Charles VI arranged a marriage of his eldest daughter, Maria Theresa, to Francis III of Lorraine. Francis relinquished the Duchy of Lorraine neighbouring France in exchange for the Grand Duchy of Tuscany to make himself a more appealing candidate for eventual election as emperor.[3] On paper, many heads of state and, most importantly, the rulers of the German states of the Holy Roman Empire, accepted the Pragmatic Sanction and the idea of Francis as the next emperor. Two key exceptions, the Electorate of Bavaria and the Electorate of Saxony, held important electoral votes and could impede or even block Francis' election.[4] When Charles died in 1740, Maria Theresa had to fight for her family's entitlements in Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia, and her husband faced competition in his election as the Holy Roman emperor.[3]

Charles Albert, Prince-elector and Duke of Bavaria, claimed the German territories of the Habsburg dynasty as a son-in-law of Joseph I, and furthermore presented himself as Charles VI's legitimate imperial successor. If women were going to inherit, he claimed, then his family should have precedence: his wife, Maria Amalia, was the daughter of Joseph I. Both Charles VI and his predecessor Joseph I had died without sons. Charles Albert of Bavaria suggested that the legitimate succession pass to Joseph's female children, rather than to the daughters of the younger brother, Charles VI.[5] For different reasons, Prussia, France, Spain, and the Polish-Saxon monarchy supported Charles of Bavaria's claim to the Habsburg territory and the Imperial title and reneged on the Pragmatic Sanction.[6]

Charles Albert of Bavaria needed military assistance to take the imperial title by force, which he secured the Treaty of Nymphenburg (July 1741). During the subsequent War of the Austrian Succession, he successfully captured Prague, where he was crowned King of Bohemia. He invaded Upper Austria, planning to capture Vienna, but diplomatic exigencies complicated his plans. His French allies redirected their troops into Bohemia, where Frederick the Great, himself newly King of Prussia, had taken advantage of the chaos in Austria and Bavaria to annex Silesia.[7]

Charles Albert's military options disappeared with the French. Adopting a new plan, he subverted the imperial election. He sold the County of Glatz to Prussia for a reduced price in exchange for Frederick's electoral vote. Charles's brother, Klemens August of Bavaria, archbishop and prince-elector of the Electorate of Cologne, voted for him in the imperial election and personally crowned him on 12 February 1742 in the traditional ceremony in Frankfurt am Main. The next day, the new Charles VII's Bavarian capital of Munich capitulated to the Austrians to avoid being plundered by Maria Theresa's troops. In the following weeks, her army overran most of Charles's territories, occupied Bavaria, and barred him from his ancestral lands and from Bohemia.[7]

Charles VII spent most of his three-year reign as emperor residing in Frankfurt while Maria Theresa battled Prussia for her patrimony in Bohemia and Hungary. Frederick could not secure Bohemia for Charles, but he did manage to push the Austrians out of Bavaria. For the last three months of his short reign, the gout-ridden Charles lived in Munich, where he died in January 1745. His son, Maximilian III Joseph (known as Max Joseph) inherited his father's electoral dignities but not his imperial ambition. With the Peace of Füssen (22 April 1745), Max Joseph promised to vote for Francis of Lorraine, Maria Theresa's husband, in the pending imperial election. He also acknowledged the Pragmatic Sanction. In return, he obtained the restitution of his family's electoral position and territories.[8] For his subjects, his negotiations ended five years of warfare and brought a generation of peace and relative prosperity that began with his father's death in 1745 and ended with his own in 1777.[9]

As the Duke of Bavaria, Max Joseph was the prince of one of the largest states in the German-speaking portion of the Holy Roman Empire. As a prince-elector, he stood in the highest rank of the Empire, with broad legal, economic, and judicial rights. As an elector, he was one of the men who selected the Holy Roman Emperor from a group of candidates.[10] He was the son of one Holy Roman Emperor (Charles VII), and the grandson of another (Joseph I). When he died of smallpox on 30 December 1777, he left no children to succeed him and several ambitious men prepared to carve his patrimony into pieces.[11]

Contenders

[edit]The Heir

[edit]

The Sulzbach branch of the Wittelsbach family inherited the Electorate of Bavaria. In this line, the 55-year-old Charles IV Theodore, the Duke of Berg-Jülich, held the first claim. Unfortunately for Charles Theodore, he was already the Elector Palatine. By the terms of the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, he had to cede the Palatine electorate to his own heir before he could claim the Bavarian electorate. He was not eager to do so, even though Bavaria was larger and more important. He preferred living in the Palatinate, with its salubrious climate and compatible social scene. He patronized the arts, and had developed in Mannheim, his capital city, an array of theaters and museums at tremendous cost to his subjects. He hosted Voltaire at one of his many palaces. During the visit, he had enticed Voltaire's secretary, the Florentine noble Cosimo Alessandro Collini (1727–1806), into his own employment, considered a coup in some of the Enlightenment circles.[12] Thomas Carlyle referred to Charles Theodore as a "poor idle creature, of purely egoistical, ornamental, dilettante nature; sunk in theatricals, [and] bastard children".[13] The French foreign minister Vergennes, who knew him, described Charles Theodore's foibles more forcefully:

Although by nature intelligent, he [Charles Theodore] has never succeeded in ruling by himself; he has always been governed by his ministers or by his father-confessor or (for a time) by the electress [his wife]. This conduct has increased his natural weakness and apathy to such a degree that for a long time he has had no opinions save those inspired in him by his entourage. The void which this indolence has left in his soul is filled with the amusements of the hunt and of music and by secret liaisons, for which His Electoral Majesty has at all times had a particular penchant.[14]

The Electress had provided him with a son, who had immediately died, but Charles Theodore's "particular penchant" for secret liaisons, most of whom were French actresses that he had raised to the status of countess, had produced several natural children. By the time of Max Joseph's death, he had legitimated seven of the males of his various alliances, and was considering the legitimation of two more.[15] With this host of male offspring, although Charles Theodore certainly wished to acquire more territory, he needed it to be territory that he could bequeath through his testament, rather than territory encumbered by a legal entailment that could only pass to a legitimate child.[16]

Deal-maker

[edit]

Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, Archduke of Austria, and co-ruler with his mother, Empress Maria Theresa, coveted Bavaria. He felt the War of the Austrian Succession had shown that the House of Habsburg-Lorraine needed a wider sphere of influence in the German-speaking parts of the Holy Roman Empire.[17] Without this, the family could not count on the election of their chosen male candidate as emperor, nor could the family count on an uncontested succession to the Habsburg territories of Bohemia, Hungary and Croatia. For most of Joseph's adult life, he sought to strengthen his family's influence in German-speaking lands. For him, this meant the acquisition of German lands (generally better-developed economically), not lands in the eastern region of the Habsburg empire, even such strategic territories as Bukovina.[18]

Joseph married Max Joseph's sister, Maria Josepha, in 1765, hoping he could claim the Bavarian electorate for his offspring. After two years of unhappy marriage, Maria Josepha died without issue. When Max Joseph died ten years later, Joseph could only present a weak legal claim to Lower Bavaria through a dubious and ancient grant made by the Emperor Sigismund to the House of Habsburg in 1425.[18] Knowing its poor legal grounds, Joseph negotiated a secret agreement with Charles Theodore shortly after Max Joseph's death. In this agreement (3 January 1778), Charles Theodore ceded Lower Bavaria to Austria in exchange for uncontested succession to the remainder of the electorate.[19] Charles Theodore also hoped to acquire from Joseph some unencumbered parts of the Austrian Netherlands and parts of Further Austria that he could bequeath to his bastards, but this was not written into the agreement and Joseph was not a particularly generous man. Furthermore, the agreement entirely ignored the interests of Charles Theodore's own heir presumptive, Charles II August, of the House of Palatinate-Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld.[20] Charles August was the presumptive heir of Charles Theodore's domains and titles. He had a clear and direct interest in the disposition of the Bavarian electorate, especially in its territorial integrity.[21]

Heir presumptive

[edit]

Unbeknownst to either Charles Theodore or Joseph, a widow (historians are uncertain which widow) opened secret negotiations with Prussia to secure the eventual succession of Charles II August (Charles August). Some historians maintain the active negotiator was Max Joseph's widow, Maria Anna Sophia of Saxony. Others assert it was Max Joseph's sister, Maria Antonia of Bavaria, who was also Charles August's mother-in-law and the mother of the reigning Elector of Saxony. Ernest Henderson even maintained she was the "only manly one among the many Wittelsbach parties" involved in the issue.[22]

Charles August was no great admirer of Joseph's. As a younger man, he had sought the hand of Joseph's sister, Archduchess Maria Amalia. She had been quite content to take him, but Joseph and their mother insisted she marry instead the better-connected Ferdinand, Duke of Parma.[23] After this disappointment, Charles II August married Maria Amalia of Saxony in 1774; she was the daughter of Frederick Christian, Elector of Saxony (d. 1763) and his wife Maria Antonia, Max Joseph's sister. In 1769, the reigning Saxon elector, Frederick Augustus III, had married Charles August's sister. Charles August, sometimes called duc de Deux-Ponts (a French translation of Zweibrücken, or two bridges), was a French client and could theoretically draw on French support for his claim. However, he had especially good relations with the Saxon Elector: both his mother- and brother-in-law wanted to ensure that Maria Amalia's husband received his rightful inheritance.[21]

Diplomacy

[edit]Interested parties

[edit]Count Karl-Wilhelm Finck von Finckenstein, Frederick the Great's prime minister, believed that any Austrian acquisition in Bavaria would shift the balance of power in the Holy Roman Empire, diminishing Prussia's influence.[24] Prussia's recent gains had been hard-won: thirty years earlier, Frederick had engaged in protracted wars in Silesia and Bohemia, resulting in Prussia's annexation of most of Silesia, and now, with the economy and society modernizing under his direction, Prussia was emerging as a great power. In the Silesian Wars and the Seven Years' War, Frederick had earned a new, if grudging, respect for his kingdom's military and diplomatic prowess from the European powers of France, Russia, Britain and Austria.[25] To protect Prussia's status and territory, Finck and Frederick constructed an alliance with the Electorate of Saxony, ostensibly to defend the rights of Charles II August, Duke of Zweibrücken.[24]

Although equally interested in maintaining its influence among the German states, France had a double problem. As a supporter of the rebellious British colonies in North America, she wished to avoid a continental engagement; she could do more damage to the British in North America than in Europe.[24] The Diplomatic Revolution in 1756 had gone against two hundred years of French foreign policy of opposition to the House of Habsburg, arguably bringing France massive territorial gains in repeated wars with Habsburg Austria and Spain.[26] A reversal of this policy in 1756 tied French foreign policy in Europe to Vienna which, although it could give France additional influence and leverage, could also cripple the country's diplomatic maneuvers with the other power players: Britain, Russia, and Prussia. Despite this restructuring, there existed in the French Court at Versailles, and in France generally, a strong anti-Austrian sentiment.[24] The personal union (the diplomatic term for marriage) of Louis, then the Dauphin, and the Austrian Archduchess Marie Antoinette, was considered both a political and matrimonial mésalliance in the eyes of many Frenchmen. It flew in the face of 200 years of French foreign policy, in which the central axiom "had been hostility to the House of Habsburg."[26] The French foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes, maintained deep-seated hostility to the Austrians that antedated the alliance of 1756. He had not approved of the shift in France's traditional bonds and considered the Austrians untrustworthy. Consequently, he managed to extricate France from immediate military obligations to Austria by 1778.[24]

-

Vergennes, foreign minister of France.

-

Frederick II (the Great).

-

Catherine II (the Great), Empress of Russia.

-

Frederick August of Saxony.

Tensions rise

[edit]On 3 January 1778, a few days after Max Joseph's death, the electoral equerry proclaimed the succession of Charles Theodore. Dragoons rode through the streets of Munich, some banging drums and some blowing trumpets, and others shouting, "Long Live our Elector Charles Theodore."[27] According to 3 January agreement between Joseph and Charles Theodore, fifteen thousand Austrian troops occupied Mindelheim, ultimately more territory than had been granted to Joseph. Charles Theodore, who had dreamed of rebuilding the Burgundian empire, realized that Joseph was not seriously planning to exchange Bavaria, or even a portion of it, for the entirety of the Austrian Netherlands. At best, he might acquire a few portions of it, perhaps Hainaut or Guelders, Luxembourg, Limburg, or various dispersed possessions in Further Austria, most of which lay in southwestern Germany, but Joseph would never release any sizable portion of territory, and certainly not any territory of strategic military or commercial value.[28]

While Charles Theodore's dream of a Burgundian renaissance receded, Joseph continued on his course to annex part of Bavaria. The widow—Max Joseph's widow or the mother-in-law or both—petitioned Prussia on behalf of Charles II August. Frederick's envoys to the heir presumptive convinced this slighted prince to lodge protests with the Imperial Diet in Regensburg.[29] Joseph's troops remained in portions of Bavaria, even establishing an Austrian administration at Straubing, precipitating a diplomatic crisis.[24] Austrian occupation of Bavaria was unacceptable to Charles August's champion, Frederick.[25] Prussian troops mobilized near Prussia's border with Bohemia, reminiscent of the invasion in 1740 that so endangered Maria Theresa's succession to the Habsburg hereditary lands. Meanwhile, the French wriggled out of their diplomatic obligations to Austria, telling Joseph that there would be no military support from Paris for a war against Prussia.[24] Britain, Prussia's strongest ally, was already mired in a war in North America, but Prussia's military had recovered from the Seven Years' War and Frederick did not require any help. Prussia's other ally, Saxony, aligned by two marriages with Charles August, was strategically prepared for war against Austria and ready to contribute twenty thousand troops.[30] Watching from Saint Petersburg, Catherine II was willing to mop up the spoils of war for the Russian Empire but did not want to get involved in another costly European conflict.[31]

For four months, negotiators shuttled between Vienna and Berlin, Dresden and Regensburg, and Zweibrücken, Munich and Mannheim.[25] By early spring 1778, Austria and Prussia faced each other with armies several times the size of their forces during the Seven Years' War, and their confrontation had the potential to explode into another European-wide war.[32]

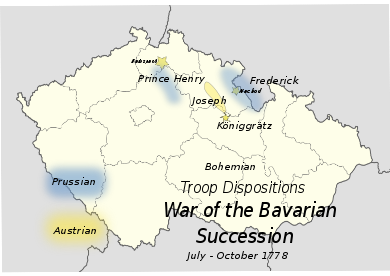

Action

[edit]When it became clear that other monarchs would not acquiesce in a de facto partition of Bavaria, Joseph and his foreign minister, Anton von Kaunitz, scoured the Habsburg realm for troops and concentrated six hundred guns and a 180,000–190,000-man Austrian army in Bohemia, Moravia, and Austrian Silesia. This amounted to most of Austria's two-hundred thousand effectives, leaving much of the Habsburg border regions with the Ottoman Empire under-guarded.[33] On 6 April 1778 Frederick of Prussia established his army of eighty thousand men on the Prussian border with Bohemia, near Neisse, Schweidnitz, and the County of Glatz,[25] which Frederick had acquired from the Wittelsbach contender in 1741 in exchange for his electoral support of Charles VII.[34] At Glatz, Frederick completed his preparations for invasion: he gathered supplies, arranged a line-of-march, brought up his artillery and drilled his soldiers. His younger brother, Prince Henry, formed a second army of seventy-five to a hundred thousand men to the north and west, in Saxony. In April, Frederick and Joseph officially joined their armies in the field, and diplomatic negotiations ended.[25]

In early July 1778, the Prussian general Johann Jakob von Wunsch (1717–1788) crossed into Bohemia near the fortified town of Náchod with several hundred men. The local garrison, commanded by Friedrich Joseph, Count of Nauendorf, then a Rittmeister (captain of cavalry), included only fifty hussars. Despite the poor numerical odds, Nauendorf sallied out to engage Wunsch's men. When his small force reached Wunsch's, he greeted the Prussians as friends; by the time the Prussians were close enough to realize the allegiance of the hussars, Nauendorf and his small band had acquired the upper hand.[35] Wunsch withdrew; the next day, Nauendorf was promoted to major.[35] In a letter to her son, the Empress Maria Theresa wrote: "They say you were so pleased with Nauendorf, a rookie from Carlstadt or Hungary, who killed seven men, that you gave him twelve ducats."[36]

Invasion

[edit]A few days after Wunsch's encounter with Nauendorf, Frederick entered Bohemia. His eighty thousand troops occupied Náchod but advanced no further. The Habsburg army stood on the heights of the Elbe river, nominally under Joseph but with Count Franz Moritz von Lacy in practical command.[37] Lacy had served under Marshal Daun during the Seven Years' War and knew his military business. He established the Austrian army on the most defensible position available: centered at Jaroměř,[38] a triple line of redoubts extended 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) southwest along the river to Königgrätz. The Austrians also augmented this defensive line with their six hundred artillery pieces.[39]

While the main Habsburg army faced Frederick at the Elbe, a smaller army under the command of Baron Ernst Gideon von Laudon guarded the passes from Saxony and Lusatia into Bohemia. Laudon was another battle-hardened and cagey commander with extensive field experience, but even he could not cover the long frontier completely. Shortly after Frederick crossed into Bohemia, Prince Henry, a brilliant strategist in his own right, maneuvered around Laudon's troops and entered Bohemia at Hainspach.[40] To avoid being flanked, Laudon withdrew across the Iser river, but by mid-August, the main Austrian army was in danger of being outflanked by Henry on its left wing. At its center and right, it faced a well-disciplined army commanded by Frederick, arguably the best tactical general of the age and feared for his victories against France and Austria in the previous war.[41]

While his main army remained entrenched on the heights above the Elbe, Joseph encouraged raids against the Prussian troops. On 7 August 1778, with two squadrons of his regiment, the intrepid "rookie", now Major Nauendorf, led a raid against a Prussian convoy at Bieberdorf in the County of Glatz. The surprised convoy surrendered and Nauendorf captured its officers, 110 men, 476 horses, 240 wagons of flour, and thirteen transport wagons.[42] This kind of action characterized the entire war. There were no major battles; the war consisted of a series of raids and counter-raids during which the opposing sides lived off the countryside and tried to deny each other access to supplies and fodder.[43] Soldiers later said they spent more time foraging for food than they did fighting.[44]

The armies remained in their encampments for the campaign season while men and horses ate all the provisions and forage for miles around.[25] Prince Henry wrote to his brother, suggesting they complete their operations by 22 August, at which time he estimated he would have exhausted local supplies of food for his men and fodder for his horses.[45] Frederick agreed. He laid plans to cross the Elbe and approach the Austrian force from the rear, but the more he examined the conditions of Joseph's entrenchments, the more he realized that the campaign was already lost. Even if he and Henry executed simultaneous attacks on the Königgrätz heights, such a plan exposed Henry to a flanking attack from Laudon. A coordinated frontal and rear assault was also unlikely to succeed. Even if it did, the Prussian losses would be unacceptable and would demolish his army's capacity to resist other invaders. From Frederick's perspective, the Russians and the Swedes were always ready to take advantage of any perceived Prussian weakness, and the French also could not be trusted to keep their distance. For Frederick, it was a risk not worth taking. Despite this realization, the four armies—two Austrian, two Prussian—remained in place until September, eating as much of the country's resources as they could.[25]

From their advantageous height by Königgrätz, the Austrians frequently bombarded the Prussian army encamped below them. On the same day that Frederick's doctors bled him, an Austrian cannonade grew so strong that Frederick rode out to observe the damage. During the ride, his vein opened. A company medic bound his wound, an incident later depicted by the painter Bernhard Rode.[46] In his admiring history of Frederick the Great, the British historian Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) relayed the story of Frederick and a Croatian marksman. As Frederick was reconnoitring, Carlyle maintained, the King encountered the Croat taking aim at him. Reportedly, he wagged his finger at the man, as if to say, "Do not do that." The Croat thought better of shooting the King, and disappeared into the woods; some reports maintain he actually knelt before the king and kissed his hand.[47]

Nauendorf continued his raids, the soldiers foraged for food and dug up the local potato crop, and Joseph and Frederick glared at one another by Königgrätz. Maria Theresa had sent Kaunitz on a secret mission to Berlin to offer a truce. In a second trip, she offered a settlement, and finally wrote to the Empress Catherine in Russia to ask for assistance. When Joseph discovered his mother's maneuvering behind his back, he furiously offered to abdicate. His mother enlisted the assistance she needed. Catherine offered to mediate the dispute; if her assistance was unacceptable, she was willing to send fifty thousand troops to augment the Prussian force, even though she disliked Frederick and her alliance with him was strictly defensive. Frederick withdrew portions of his force in mid-September. In October, Joseph withdrew most of his army to the Bohemian border and Frederick withdrew his remaining troops into Prussia. Two small forces of hussars and dragoons remained in Bohemia to provide a winter cordon; these forces allowed Joseph and Frederick to keep an eye on each other's troops while their diplomats negotiated at Teschen.[25]

Winter actions

[edit]Appointed as the commander of the Austrian winter cordon, Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser ordered a small assault-column under the command of Colonel Wilhelm Klebeck to attack the village of Dittersbach.[Note 1] Klebeck led a column of Croats into the village. During the action, four hundred Prussians were killed, another four hundred made prisoner, and eight colors were captured.[48] Following his successes against the Prussians in 1778, Joseph awarded Wurmser the Knight's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa on 21 October 1778.[49]

In another raid, on 1 January 1779, Colonel Franz Levenehr led 3,200 men (four battalions, six squadrons, and 16 artillery) into Zuckmantel, a village in Silesia on the Prussian border, 7 kilometers (4 mi) south of Ziegenhals. There he ran against a 10,000-man Prussian force commanded by General Johann Jakob von Wunsch; the Austrians decisively defeated the Prussians, with a loss of 20 men (wounded) against the Prussian losses of 800.[50][Note 2] Two weeks later, Wurmser advanced into the County of Glatz in five columns, two of which, commanded by Major General Franz Joseph, Count Kinsky, surrounded Habelschwerdt on 17–18 January. While one column secured the approach, the other, under the leadership of Colonel Pallavicini,[Note 3] stormed the village and captured the Landgrave of Hessen-Philippsthal, 37 officers, plus 700 to 1,000 men, three cannon and seven colors; in this action, the Prussians lost 400 men dead or wounded. Wurmser himself led the third column in an assault on the so-called Swedish blockhouse at Oberschwedeldorf.[51] It and the village of Habelschwerdt were set on fire by howitzers. Major General Terzy (1730–1800), who was covering with the remaining two columns, threw back the enemy support and took three hundred Prussian prisoners. Meanwhile, Wurmser maintained his position at the nearby villages of Rückerts and Reinerz.[41] His forward patrols reached the outskirts of Glatz and patrolled much of the Silesian border with Prussia near Schweidnitz.[48] Halberschwerdt and Oberschedeldorf were both destroyed.[52]

On 3 March 1779, Nauendorf again raided Berbersdorf with a large force of infantry and hussars and captured the entire Prussian garrison. Joseph awarded him the Knight's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa (19 May 1779).[42]

Impact

[edit]

In the Treaty of Teschen (May 1779), Maria Theresa returned Lower Bavaria to Charles Theodore, but kept the so-called Innviertel, a 2,200-square-kilometer (850 sq mi) strip of land in the drainage basin of the Inn river. She and Joseph were surprised to find that the small territory had 120,000 inhabitants.[25] Saxony received a financial reward of six million gulden from the principal combatants[53] for its role in the intervention.[54]

The War of the Bavarian Succession was the last war for both Frederick and Maria Theresa, whose reigns began and ended with wars against one another.[55] Although they deployed armies three to four times the size of the armies of the Seven Years' War,[55] neither monarch used the entirety of the military force each had at their disposal, making this war-without-battles remarkable.[54] Despite the restraint of the monarchs, some early nineteenth-century casualty estimates suggest that tens of thousands died of starvation and hunger-related disease.[56] Carlyle's more moderate estimate lies at about ten thousand Prussian and probably another ten thousand Austrian dead.[57] Michael Hochedlinger assesses combined casualties at approximately thirty thousand;[58] Robert Kann gives no estimate of casualties but suggests the primary causes of death were cholera and dysentery.[59] Gaston Bodart, whose 1915 work is still considered the authority on Austrian military losses, is specific: five Austrian generals (he does not name them), over twelve thousand soldiers, and 74 officers died of disease. In minor actions and skirmishes, nine officers and 265 men were killed and four officers and 123 men were wounded, but not fatally. Sixty-two officers and 2,802 men were taken prisoner, and 137 men were missing. Over three thousand Imperial soldiers deserted. Finally, twenty-six officers and 372 men were discharged with disabilities. Bodart also gives Prussian losses: one general killed (he does not say which), 87 officers and 3,364 men killed, wounded or captured. Overall, he assumes losses of ten percent of the fighting force.[60] Little has been discovered of civilian casualties, although certainly the civilians also suffered from starvation and disease. There were other damages: for example, Habelschwerdt and one of its hamlets were destroyed by fire.[61]

Despite its short duration, the war itself cost Prussia 33 million florins.[56] For the Austrians, the cost was higher: 65 million florins, for a state with an annual revenue of 50 million florins.[62] Joseph himself described war as "a horrible thing ... the ruin of many innocent people."[63]

Change in warfare

[edit]This was the last European war of the old style, in which armies maneuvered sedately at a distance while diplomats hustled between capitals to resolve the monarchs' differences. Given the length of time—six months—the cost in life and treasure was high. In light of the scale of warfare experienced in Europe less than a generation later in the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars, though, this six-month engagement seems mild.[64] Yet while historians often dismissed it as the last of the archaic mode of Ancien Régime warfare, elements of the war foreshadowed conflicts to come: the sheer sizes of the armies deployed reflected emerging abilities and willingness to conscript, train, equip and field larger armies than had been done in previous generations.[65]

The war also reflected a new height in military spending, especially by the Habsburgs. After the Seven Years' War, the size of the Habsburg military shrank, from 201,311 men in arms in 1761 to 163,613 in 1775. In preparing for a second summer's campaign, Joseph's army grew from 195,108 effectives in the summer of 1778 to 308,555 men in arms in Spring 1779.[66] Habsburg military strength never dropped below two hundred thousand effectives between 1779 and 1792, when Austria entered the War of the First Coalition. Several times it surged above three hundred thousand men in arms, responding to needs on the Ottoman border or the revolt in the Austrian Netherlands. The military also underwent a massive organizational overhaul.[67]

In the vernacular, the Austrians called the war Zwetschgenrummel ("Plum Fuss"), and for the Prussians and Saxons, it was Kartoffelkrieg ("Potato War"). In the historiography of European warfare, historians almost always describe the War of the Bavarian Succession "in dismissive or derisive terms [as] the apotheosis (or perhaps caricature) of old regime warfare," despite its grand name.[68] Some historians have maintained that the focus on the consumption of the produce of the land gave the war its popular name. Others suggest that the two armies lobbed potatoes instead of cannonballs or mortars.[69] A third theory maintains that the war acquired its popular name because it took place during the potato harvest.[70]

Resurgence of the problem

[edit]The underlying problem was not solved: Joseph's foreign policy dictated the expansion of Habsburg influence over German-speaking territories, and only this, he believed, would counter Prussia's growing strength in Imperial affairs. In 1785, Joseph again sought to make a territorial deal with Charles Theodore, again offering to trade portions of Bavarian territory for portions of the Austrian Netherlands. This time it would be a straight trade: territory for territory, not a partition.[71] Although the Austrian Netherlands was a wealthy territory, it was a thorn in Joseph's side, opposing his administrative and bureaucratic reforms and devouring military and administrative resources he desperately needed elsewhere in his realm.[72] Despite its problems, Joseph could not afford to give up the Netherlands entirely, so his efforts to negotiate a partial territorial exchange guaranteed him some of the financial benefits of both his Netherlands possessions and the Bavarian territories.[73]

Even if Joseph had to give up the Austrian Netherlands, it meant "the barter of an indefensible strategic position and ... an economic liability for a great territorial and political gain, adjacent to the monarchy."[59] Again, Charles II August, Duke of Zweibrücken, resented the possible loss of his Bavarian expectancy, and again, Frederick of Prussia offered aid. This time, no war developed, not even a "Potato War". Instead, Frederick founded the Fürstenbund, or the Union of Princes, comprising the influential princes of the northern German states, and these individuals jointly pressured Joseph to relinquish his ambitious plans. Rather than increasing Austria's influence in German affairs, Joseph's actions increased Prussian influence, making Prussia seem like a protector state against greedy Habsburg imperialism (an ironic contrast to the earlier stage of the Austro-Prussian rivalry, in which Frederick seized German-speaking lands with military force and without formal declaration of war, causing most of the German states to join Austria). In 1799, Bavaria and the Palatinate passed to Maximilian IV Joseph, brother of Charles August, whose only child had died in 1784.[74]

Long-term effect: the intensification of German dualism

[edit]Joseph understood the problems facing his multi-ethnic patrimony and the ambivalent position the Austrians held in the Holy Roman Empire. Although the Habsburgs and their successor house of Habsburg-Lorraine had, with two exceptions, held the position of Emperor since the early 15th century, the basis of 18th-century Habsburg power lay not in the Holy Roman Empire itself, but in Habsburg territories in Eastern Europe, where the family had vast domains. For Joseph or his successors to wield influence in the German-speaking states, they needed to acquire additional German-speaking territories.[63] Acquisition of Central European territories with German-speaking subjects would strengthen the Austrian position in the Holy Roman Empire. As far as Joseph was concerned, only this could shift the center of the Habsburg empire into German-speaking Central Europe. This agenda made dispensable both the Austrian Netherlands—Habsburg territories which lay furthest west—and Galicia, furthest east. It also made the recovery of German-speaking Silesia and acquisition of new territories in Bavaria essential.[75]

By the late 1770s, Joseph also faced important diplomatic obstacles in consolidating Habsburg influence in Central Europe. When the British had been Austria's allies, Austria could count on British support in its wars, but Britain was now allied with Prussia. In the Diplomatic Revolution, the French replaced the British as Austria's ally, but they were fickle, as Joseph discovered when Vergennes extricated Versailles from its obligations. Russia, which also had been an important Austrian ally for most of the Seven Years' War, sought opportunities for expansion at the expense of its weak neighbors. In 1778, that meant Poland and the Ottomans, but Joseph fully understood the danger of appearing weak in Russia's eyes: Habsburg lands could be carved off easily by Catherine's diplomatic knife. Still, Frederick of Prussia was the most definite enemy, as he had been throughout the reigns of Theresa and Franz before him, when the Prussian state's emergence as a player on the European stage had occurred at Habsburg expense, first with the loss of Silesia, and later in the 1750s and 1760s.[75] Joseph sought to unify the different portions of his realm, not the German states as a whole, and to establish Habsburg hegemony in German-speaking central Europe beginning with the partition of Bavaria.[76]

The broad geographic outlines of European states changed rapidly in the last fifty years of the century, with partitions of Poland and territorial exchanges through conquest and diplomacy. Rulers sought to centralize their control over their domains and create well-defined borders within which their writ was law.[77] For Joseph, the acquisition of Bavaria, or at least parts of it, would link Habsburg territories in Bohemia with those in the Tyrol and partially compensate Austria for its loss of Silesia. The Bavarian succession crisis provided Joseph with a viable opportunity to consolidate his influence in the Central European states, to bolster his financially strapped government with much-needed revenue, and to strengthen his army with German-speaking conscripts. Supremacy in the German states was worth a war,[78] but for Frederick, the preservation of Charles August's inheritance was not. He had had sufficient war in the first years of his reign, and in its last twenty years, he sought to preserve the status quo, not to enter into risky adventures that might upset it. If he had to withdraw from engagement with Joseph's army, such a sacrifice was a temporary measure. Warfare was only one means of diplomacy, and he could employ others in this contest with Austria.[79] The Austro-Prussian dualism that dominated the next century's unification movement rumbled ominously in the War of the Bavarian Succession.[80]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Shortly afterward, Klebeck was elevated to the rank of baron (Freiherr) and awarded the Knight's Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresa (15 February 1779). Digby Smith. Klebeck. Leonard Kudrna and Digby Smith, compilers. A biographical dictionary of all Austrian Generals in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1792–1815. Napoleon Series. Robert Burnham, Editor in Chief. April 2008. Accessed 22 March 2010.

- ^ On 15 February, Levenehr was elevated to the rank of baron (Freiherr). See Almanach de la Cour Imperiale et Royale: pour l'année Österreich, Trattner, 1790, p. 105.

- ^ This officer was probably Colonel, later Count, Carlo Pallavicini, of the House of Pallavicini, who had been in Habsburg service since the latter days of the Seven Years War. Erik Lund. War for the every day: generals, knowledge and warfare in early modern Europe. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-313-31041-6, p. 152.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Gaston Bodart. Losses of life in modern wars, Austria-Hungary and France. Vernon Lyman Kellogg, trans. Oxford: Clarendon Press; London & New York: H. Milford, 1916, p. 37.

- ^ Michael Hochedlinger. Austria's Wars of Emergence, 1683–1799. London: Longman, 2003, p. 246.

- ^ a b Marshall Dill. Germany: A Modern History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1970, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Hochedlinger, p. 246.

- ^ Dill, pp. 49–50; Hajo Holborn. A History of Modern Germany, The Reformation, Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1959, pp. 191–247.

- ^ Alfred Benians. Cambridge Modern History. volume 6, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1901–1912, pp. 230–233; Dill, pp. 49–50; Holborn, pp. 191–247.

- ^ a b Benians, pp. 230–233; Dill, pp. 49–50; Holborn, pp. 191–247.

- ^ Hochedlinger, p. 258.

- ^ Charles Ingrao. "Review of Alois Schmid, Max III Joseph und die europaische Macht." The American Historical Review, Vol. 93, No. 5 (Dec., 1988), p. 1351.

- ^ See Holborn, pp. 191–247, for general descriptions of the status of the electors in the Holy Roman Empire.

- ^ Jean Berenger. A History of the Habsburg Empire 1700–1918. C. Simpson, Trans. New York: Longman, 1997, ISBN 0-582-09007-5. pp. 96–97.

- ^ (in German) Jörg Kreutz: Cosimo Alessandro Collini (1727–1806). Ein europäischer Aufklärer am kurpfälzischen Hof. Mannheimer Altertumsverein von 1859 – Gesellschaft d. Freunde Mannheims u. d. ehemaligen Kurpfalz; Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim; Stadtarchiv – Institut f. Stadtgeschichte Mannheim (Hrsg.). Mannheimer historische Schriften Bd. 3, Verlag Regionalkultur, 2009, ISBN 978-3-89735-597-2.

- ^ Thomas Carlyle. History of Friedrich II of Prussia called Frederick the great: in eight volumes. Vol. VIII in The works of Thomas Carlyle in thirty volumes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1896–1899, p. 193.

- ^ J. C. Easton. "Charles Theodore of Bavaria and Count Rumford." The Journal of Modern History Vol. 12, No. 2 (Jun., 1940), pp. 145–160, pp. 145–146 quoted.

- ^ Paul Bernard. Joseph II and Bavaria: Two Eighteenth Century Attempts at German Unification. Hague: Martin Nijoff, 1965, p. 40.

- ^ Henry Smith Williams. The Historians' History of the World: a comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations as recorded by the great writers of all ages. London: The Times, 1908, p. 245.

- ^ Robert A. Kann. A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974, ISBN 0-520-04206-9, Chapter III, particularly pp. 70–90, and Chapter IV, particularly pp. 156–169.

- ^ a b Timothy Blanning. The Pursuit of Glory: Europe 1648–1815. New York: Viking, 2007. ISBN 978-0-670-06320-8, p. 591. See also Kann, p. 166.

- ^ Review of Harold Temperley. Frederick II and Joseph II. An Episode of War and Diplomacy in the Eighteenth Century. Sidney B. Fay. "Untitled Review." The American Historical Review. Vol. 20, No. 4 (Jul., 1915), pp. 846–848.

- ^ Blanning, Pursuit of Glory, p. 591. Henderson, p. 214. Williams, p. 245.

- ^ a b Berenger, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Ernest Flagg Henderson A Short History of Germany. New York: Macmillan, 1917, p. 214. Others argue it was the widow of Max Joseph's younger brother, but this brother had died in childhood. See also Christopher Thomas Atkinson, A history of Germany, 1715–1815. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1969 [1908], p. 313.

- ^ Julia P. Gelardi. In Triumph's Wake: Royal Mothers, Tragic Daughters, and the Price They Paid. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-312-37105-0, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d e f g Berenger, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hochedlinger, p. 367.

- ^ a b T. C. W. Blanning. The French Revolutionary Wars New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-340-56911-5, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Robert Spaethling (ed.). Mozart's Letters, Mozart's Life. New York: Norton, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04719-9, p. 117.

- ^ Hochedlinger, pp. 366–367.

- ^ Robert Gutman. Mozart: a cultural biography. New York: Harcourt, 2000. ISBN 0-15-601171-9, pp. 392–393.

- ^ Hochedlinger, p. 367

- ^ Brendan Simms. Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. New York: Penguin Books, 2008, pp. 624–625.

- ^ Simms, pp. 624–625.

- ^ Blanning, Pursuit of Glory, p. 608. Bodart places the number at approximately 190,000 in Gaston Bodart, Losses of life in modern wars, Austria-Hungary and France. Vernon Lyman Kellogg, trans. Oxford, Clarendon Press; London, New York [etc.] H. Milford, 1916, p. 37. Hochedlinger, p. 367, says it was 180,000.

- ^ Benians. pp. 230–233; Dill, pp. 49–50; Henderson. p. 127; and Holborn, pp. 191–247.

- ^ a b (in German) Jens-Florian Ebert. "Nauendorf, Friedrich August Graf." Die Österreichischen Generäle 1792–1815. Accessed 15 October 2009; (in German) Constant von Wurzbach. "Nauendorf, Friedrich August Graf." Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich, enthaltend die Lebensskizzen der denkwürdigen Personen, welche seit 1750 in den österreichischen Kronländern geboren wurden oder darin gelebt und gewirkt haben. Wien: K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerie [etc.] 1856–91, Volume 20, pp. 103–105, p. 103 cited.

- ^ (in French) "Maria Theresa to Joseph, 17 July 1778." Maria Theresa, Empress and Joseph, Holy Roman Emperor. Maria Theresia und Joseph II. Ihre Correspondenz sammt Briefen Joseph's an seinen Bruder Leopold. Wien: C. Gerold's Sohn, 1867–68, pp. 345–346. Full text is: (in French) "On dit que vous avez été si content de Nauendorf, d'un recrue Carlstätter ou hongrois qui a tué sept hommes, que vous lui avez donné douze ducats;..."

- ^ Carlyle, p. 203, maintained that Joseph's brother Leopold was also there.

- ^ Benians maintains it was centered on Jaroměřice, p. 703.

- ^ Benians, pp. 703–705. Hochedlinger, p. 367. See also Fortress Josefov.

- ^ Benians, p. 706.

- ^ a b Hochedlinger, p. 368.

- ^ a b (in German) Ebert, "Nauendorf."

- ^ Hochedlinger, p. 368. Williams, p. 245.

- ^ Dill, p. 52.

- ^ Benians, p. 707.

- ^ Berlin Art Academy, "Friedrich der Große und der Feldscher um 1793–94, von Bernhard Rohde." Katalog der Akademieausstellung von 1795. Berlin, 1795.

- ^ Carlyle, p. 204.

- ^ a b (in German) Constant Wurzbach. Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Österreich. Vienna, 1856–91, vol 59, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Digby Smith. Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser. Leonard Kurdna and Digby Smith, compilers. A biographical dictionary of all Austrian Generals in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1792–1815. Napoleon Series. Robert Burnham, Editor in Chief. April 2008. Accessed 22 March 2010.

- ^ (in German) Gaston Bodart, Militär-historisches kreigs-lexikon, (1618–1905), Vienna, Stern, 1908, p. 256.

- ^ Oscar Criste. "Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser." Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. Herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 44 (1898), S. 338–340, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe in Wikisource. (Version vom 24. März 2010, 3:18 Uhr UTC). Criste claims 700 men; Bodart's numbers are higher.

- ^ Carlyle, p. 219. Criste, ADB. Wurzbach, p. 5.

- ^ (in German) Autorenkollektiv. Sachsen (Geschichte des Kurfürstentums bis 1792). Meyers Konversationslexikon. Leipzig und Wien: Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, Vierte Auflage, 1885–1892, Band 14, S. 136.

- ^ a b Williams, p. 245.

- ^ a b Blanning, Pursuit of Glory, pp. 610–611.

- ^ a b So posits William Conant Church in his anti-war essay: "Our Doctors in the Rebellion." The Galaxy, volume 4. New York, W.C. & F.P. Church, Sheldon & Company, 1868–78, p. 822. This amounts to approximately US$10 million circa 1792, or $232 million in 2008 (in Consumer Price Index).

- ^ Carlyle, p. 219.

- ^ Hochedlinger, p. 369.

- ^ a b Kann, p. 166.

- ^ Bodart, p. 37.

- ^ (in German) Oscar Criste. Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser. Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. Herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 44 (1898), S. 338–340, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe in Wikisource. (Version vom 24. März 2010, 13:18 Uhr UTC).

- ^ Hochedlinger, p. 385. Robin Okey. The Habsburg Monarchy. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2001, ISBN 0-312-23375-2, p. 38.

- ^ a b Okey, p. 47.

- ^ Hochedlinger, p.385.

- ^ Blanning, Pursuit of Glory. pp. 609–625.

- ^ Hochedlinger, p. 300.

- ^ Hochedlinger, pp. 300 and 318–326.

- ^ Blanning, Pursuit of Glory. p. 590.

- ^ See Benians, p. 707, Dill, p. 52, Henderson, p. 213, Simms, pp. 624–625, and Williams, p. 245.

- ^ Berenger, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Harold W. V. Temperley. Frederic the Great and Kaiser Joseph: an episode of war and diplomacy in the eighteenth century. London: Duckworth, 1915, pp. vii–viii.

- ^ Blanning. The French Revolutionary Wars, Chapter II.

- ^ Emile Karafiol. "Untitled review." The Journal of Modern History. Vol 40, No. 1 (March 1967), pp. 139–140 [140].

- ^ Dill, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Berenger, pp. 43–47; Okey, pp. 37, 46.

- ^ Paul Bernard. Joseph II and Bavaria: Two Eighteenth Century Attempts at German Unification. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1965.

- ^ Bergenger, p. 47. Karafiol, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Karafiol, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Fay, p. 847.

- ^ Christopher M. Clark. Iron Kingdom: the rise and downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2006. ISBN 0-674-02385-4, pp. 216–217. Okey, pp. 47–48.

Sources

[edit]- Atkinson, Christopher Thomas. A history of Germany, 1715–1815. New York: Barnes and Noble, 1969 [1908].

- (in German) Autorenkollektiv. Sachsen (Geschichte des Kurfürstentums bis 1792). Meyers Konversationslexikon. Leipzig und Wien: Verlag des Bibliographischen Instituts, Vierte Auflage, 1885–1892, Band 14, S. 136.

- Bernard, Paul. Joseph II and Bavaria: Two Eighteenth Century Attempts at German Unification. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1965.

- Benians, E. A. et al. The Cambridge History of Modern Europe. Volume 6, Cambridge: University Press, 1901–12.

- Berenger, Jean. A History of the Habsburg Empire 1700–1918. C. Simpson, Trans. New York: Longman, 1997, ISBN 0-582-09007-5.

- Blanning, Timothy. The French Revolutionary Wars. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-340-56911-5.

- Blanning, T. C. W. The Pursuit of Glory: Europe 1648–1815. New York: Viking, 2007. ISBN 978-0-670-06320-8.

- Bodart, Gaston. Losses of life in modern wars, Austria-Hungary and France. Vernon Lyman Kellogg, trans. Oxford: Clarendon Press; London & New York: H. Milford, 1916.

- (in German) Bodart, Gaston. Militär-historisches kreigs-lexikon, (1618–1905). Vienna, Stern, 1908.

- Carlyle, Thomas. History of Friedrich II of Prussia called Frederick the great: in eight volumes. Vol. VIII in The works of Thomas Carlyle in thirty volumes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1896–1899.

- Church, William Conant. "Our Doctors in the Rebellion." The Galaxy, volume 4. New York: W.C. & F.P. Church, Sheldon & Company, 1866–68; 1868–78.

- Clark, Christopher M.. Iron Kingdom: the rise and downfall of Prussia, 1600–1947. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2006. ISBN 0-674-02385-4.

- (in German) Criste, Oscar. Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser. Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. Herausgegeben von der Historischen Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 44 (1898), S. 338–340, Digitale Volltext-Ausgabe in Wikisource. (Version vom 24. März 2010, 13:18 Uhr UTC).

- Dill, Marshal. Germany: a Modern history. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1970.

- (in German) Ebert, Jens-Florian. "Nauendorf, Friedrich August Graf." Die Österreichischen Generäle 1792–1815. Napoleononline (de): Portal zu Epoch. Jens Florian Ebert, editor. Oktober 2003. Accessed 15 October 2009.

- Easton, J. C.. "Charles Theodore of Bavaria and Count Rumford." The Journal of Modern History. Vol. 12, No. 2 (Jun., 1940), pp. 145–160.

- "Maximilian III Joseph".In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 December 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Fay, Sidney B. "Untitled Review." The American Historical Review. Vol. 20, No. 4 (Jul., 1915), pp. 846–848.

- Gelardi, Julia P. In Triumph's Wake: Royal Mothers, Tragic Daughters, and the Price They Paid. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-312-37105-0.

- Gutman, Robert. Mozart: a cultural biography. New York: Harcourt, 2000. ISBN 0-15-601171-9.

- Henderson, Ernest Flagg. A Short History of Germany (volume 2). New York: Macmillan, 1917.

- Hochedlinger, Michael. Austria's Wars of Emergence, 1683–1797. London: Longwood, 2003, ISBN 0-582-29084-8.

- Holborn, Hajo. A History of Modern Germany, The Reformation. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1959.

- Ingrao, Charles. "Review of Alois Schmid, Max III Joseph und die europaische Macht." The American Historical Review, Vol. 93, No. 5 (Dec., 1988), p. 1351.

- Kann, Robert A. A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974, ISBN 0-520-04206-9.

- Karafiol, Emile. Untitled review. The Journal of Modern History. Vol 40, No. 1 March 1967, pp. 139–140.

- (in German) Kreutz, Jörg. Cosimo Alessandro Collini (1727–1806). Ein europäischer Aufklärer am kurpfälzischen Hof. Mannheimer Altertumsverein von 1859 – Gesellschaft d. Freunde Mannheims u. d. ehemaligen Kurpfalz; Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen Mannheim; Stadtarchiv – Institut f. Stadtgeschichte Mannheim (Hrsg.). Mannheimer historische Schriften Bd. 3, Verlag Regionalkultur, 2009, ISBN 978-3-89735-597-2.

- Lund, Eric. War for the every day: generals, knowledge and warfare in early modern Europe. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-313-31041-6.

- (in French and German) Maria Theresia und Joseph II. Ihre Correspondenz sammt Briefen Josephs an seinen Bruder Leopold. Wien, C. Gerold's Sohn, 1867–68.

- Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus, Robert Spaethling. Mozart's Letters, Mozart's Life. New York: Norton, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04719-9.

- Okey, Robin. The Habsburg Monarchy. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2001, ISBN 0-312-23375-2.

- Simms, Brendan. Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the British Empire. New York: Penguin Books, 2008.

- Smith, Digby. Klebeck. Dagobert von Wurmser. Leonard Kudrna and Digby Smith, compilers. A biographical dictionary of all Austrian Generals in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1792–1815. The Napoleon Series. Robert Burnham, Editor in Chief. April 2008. Accessed 22 March 2010.

- Williams, Henry Smith. The Historians' History of the World: a comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations as recorded by the great writers of all ages. London: The Times, 1908.

- Temperley, Harold. Frederick II and Joseph II. An Episode of War and Diplomacy in the Eighteenth Century. London: Duckworth, 1915.

- (in German) Wurzbach, Constant. Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Österreich. Vienna, 1856–91, vol 59.

- Vehse, Eduard and Franz K. F. Demmler. Memoirs of the court and aristocracy of Austria. vol. 2. London, H.S. Nichols, 1896.

Further reading

[edit]20th century

[edit]- (in German) Kotulla, Michael, "Bayerischer Erbfolgekrieg." (1778/79), In: Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte vom Alten Reich bis Weimar (1495–1934). [Lehrbuch], Springer, Berlin: Heidelberg 2008, ISBN 978-3-540-48705-0.

- (in German) Ziechmann, Jürgen, Der Bayerische Erbfolge-Krieg 1778/1779 oder Der Kampf der messerscharfen Federn. Edition Ziechmann, Südmoslesfehn 2007,

- (in German) Groening, Monika . Karl Theodors stumme Revolution: Stephan Freiherr von Stengel, 1750–1822, und seine staats- und wirtschaftspolitischen Innovationen in Bayern, 1778–99. Obstadt-Weiher: Verlag regionalkultur, [2001].

- (in Russian) Nersesov, G.A. . Politika Rossii na Teshenskom kongresse: 1778–1779. No publication information.

- Thomas, Marvin Jr. Karl Theodor and the Bavarian Succession, 1777–1778: a thesis in history. Pennsylvania State University, 1980.

- (in German) Criste, Oskar. Kriege unter Kaiser Josef II. Nach den Feldakten and anderen authentischen Quellen. Wien: Verlag Seidel, 1904.

19th century

[edit]- (in German) Reimann, Eduard. Geschichte des bairischen Erbfolgekrieges no publication information. 1869.

- (in German) Geschichte des Baierischen Erbfolgestreits [microform] : nebst Darstellung der Lage desselben im Jenner 1779. Frankfurt & Leipzig: [s.n.], 1779.

- (in French) Neufchâteau, Nicolas Louis François de (comte). Histoire de l'occupation de la Baviere par les Autrichiens, en 1778 et 1779; contenant les details de la guerre et des negotiations que ce different occasionna, et qui furent terminées, en 1779, par la paix de Teschen. Paris: Imprimerieimperiale, [1805].

- (in German) Thamm, A. T. G. Plan des Lagers von der Division Sr. Excel. des Generals der Infanterie von Tauenzien zwischen Wisoka und Praschetz vom 7ten bis 18ten July 1778. no publication information, 1807.

18th century

[edit]- (in German) Historische Dokumentation zur Eingliederung des Innviertels im Jahre 1779: Sonderausstellung: Innviertler Volkskundehaus u. Galerie d. Stadt Ried im Innkreis, 11. Mai bis 4. Aug. 1979. (Documents relating to the annexation of the Innviertel in 1779.)

- (in German) Geschichte des Baierischen Erbfolgestreits nebst Darstellung der Lage desselben im Jenner 1779. Frankfurt: [s.n.], 1779.

- (in German) [Seidl, Carl von]. Versuch einer militärischen Geschichte des Bayerischen Erbfolge-Krieges im Jahre 1778, im Gesichtspunkte der Wahrheit betrachtet von einem Königl. Preussischen Officier. no publication information.

- (in German) Bourscheid, J. Der erste Feldzug im vierten preussischen Kriege: Im Gesichtspunkte der Strategie beschreiben. Wien: [s.n.], 1779.

- (in French) Keith, Robert Murray. Exposition détaillée des droits et de la conduite de S.M. l'imṕératrice reine apostolique rélativement à la succession de la Bavière: pour servir de réponse à l'Exposé des motifs qui ont engagé S.M. le roi de Prusse à s'opposer au démembrement de la Bavière. Vienne: Chez Jean Thom. Nob. de Trattnern, 1778.

- Frederick. Memoirs from the Peace of Hubertsburg, to the Partition of Poland, and of the Bavarian War. London: printed for G. G. J. and J. Robinson, 1789.

- 1778 in the Habsburg monarchy

- 1779 in the Habsburg monarchy

- Conflicts in 1778

- Conflicts in 1779

- History of the potato

- Wars of succession involving the states and peoples of Europe

- Wars involving the Habsburg monarchy

- Wars involving Prussia

- 1770s in the Holy Roman Empire

- 18th century in Bavaria

- House of Wittelsbach

- Wars involving Saxony

- Wars involving Bavaria

- Rebellions against the Habsburg monarchy

- Frederick the Great

- Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor