Islamic Cairo

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Cairo Governorate, Egypt |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (v), (vi) |

| Reference | 89 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Area | 523.66 ha (1,294.0 acres) |

| Coordinates | 30°02′45.61″N 31°15′45.78″E / 30.0460028°N 31.2627167°E |

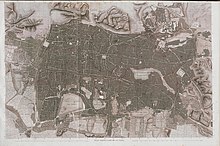

Islamic Cairo (Arabic: قاهرة المعز, romanized: Qāhira al-Muʿizz, lit. 'Al-Mu'izz's Cairo'), or Medieval Cairo, officially Historic Cairo (القاهرة التاريخية al-Qāhira tārīkhiyya), refers mostly to the areas of Cairo, Egypt, that were built from the Muslim conquest in 641 CE until the city's modern expansion in the 19th century during Khedive Ismail's rule, namely: the central parts within the old walled city, the historic cemeteries, the area around the Citadel of Cairo, parts of Bulaq, and Old Cairo (Arabic: مصر القديمة, lit. 'Misr al-Qadima') which dates back to Roman times and includes major Coptic Christian monuments.[1][2]

The name "Islamic" Cairo refers not to a greater prominence of Muslims in the area but rather to the city's rich history and heritage since its foundation in the early period of Islam, while distinguishing it from with the nearby Ancient Egyptian sites of Giza and Memphis.[3][4] This area holds one of the largest and densest concentrations of historic architecture in the Islamic world.[3]: 7 It is characterized by hundreds of mosques, tombs, madrasas, mansions, caravanserais, and fortifications dating from throughout the Islamic era of Egypt.

In 1979, UNESCO proclaimed Historic Cairo a World Cultural Heritage site, as "one of the world's oldest Islamic cities, with its famous mosques, madrasas, hammams and fountains" and "the new centre of the Islamic world, reaching its golden age in the 14th century."[5]

History

[edit]The foundation of Fustat and the early Islamic era

[edit]

The history of Cairo begins, in essence, with the conquest of Egypt by Muslim Arabs in 640, under the commander 'Amr ibn al-'As.[6] Although Alexandria was the capital of Egypt at that time (and had been throughout the Ptolemaic, Roman, and Byzantine periods), the Arab conquerors decided to establish a new city called Fustat to serve as the administrative capital and military garrison center of Egypt. The new city was located near a Roman-Byzantine fortress known as Babylon on the shores of the Nile (now located in Old Cairo), southwest of the later site of Cairo proper (see below). The choice of this location may have been due to several factors, including its slightly closer proximity to Arabia and Mecca, the fear of strong remaining Christian and Hellenistic influence in Alexandria, and Alexandria's vulnerability to Byzantine counteroffensives arriving by sea (which did indeed occur).[6][7] Perhaps even more importantly, the location of Fustat at the intersection of Lower Egypt (the Nile Delta) and Upper Egypt (the Nile Valley further south) made it a strategic place from which to control a country that was centered on the Nile river, much as the Ancient Egyptian city of Memphis (located just south of Cairo today) had done.[6][7] (The pattern of founding new garrison cities inland was also one that was repeated throughout the Arab conquests, with other examples such as Qayrawan in Tunisia or Kufa in Iraq.[7]) The foundation of Fustat was also accompanied by the foundation of Egypt's (and Africa's) first mosque, the Mosque of 'Amr ibn al-'As, which has been much rebuilt over the centuries but still exists today.[3]

Fustat quickly grew to become Egypt's main city, port, and economic center, with Alexandria becoming more of a provincial city.[7] In 661 the Islamic world came under the control of the Umayyads, based in their capital at Damascus, until their overthrow by the Abbasids in 750. The last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II, made his last stand in Egypt but was killed on August 1, 750.[6] Thereafter Egypt, and Fustat, passed under Abbasid control. The Abbasids marked their new rule in Egypt by founding a new administrative capital called al-'Askar, slightly northeast of Fustat, under the initiative of their governor Abu 'Aun. The city was completed with the foundation of a grand mosque (called Jami' al-'Askar) in 786, and included a palace for the governor's residence, known as the Dar al-'Imara.[6] Nothing of this city remains today, but the foundation of new administrative capitals just outside the main city became a recurring pattern in the history of the area.

Ahmad Ibn Tulun was a Turkish military commander who had served the Abbasid caliphs in Samarra during a long crisis of Abbasid power.[8] He became governor of Egypt in 868 but quickly became its de facto independent ruler, while still acknowledging the Abbasid caliph's symbolic authority. He grew so influential that the caliph later allowed him to also take control of Syria in 878.[6] During this period of Tulunid rule (under Ibn Tulun and his sons), Egypt became an independent state for the first time since Roman rule was established in 30 BC.[6] Ibn Tulun founded his own new administrative capital in 870, called al-Qata'i, just northwest of al-Askar. It included a new grand palace (still called Dar al-'Imara), a hippodrome or military parade ground, amenities such as a hospital (bimaristan), and a great mosque which survives to this day, known as the Mosque of Ibn Tulun, built between 876 and 879.[8][6] Ibn Tulun died in 884 and his sons ruled for a few more decades until 905 when the Abbasids sent an army to reestablish direct control and burned al-Qata'i to the ground, sparing only the mosque.[6] After this, Egypt was ruled for a while by another dynasty, the Ikhshidids, who ruled as Abbasid governors between 935 and 969. Some of their constructions, particularly under Abu al-Misk Kafur, a black eunuch (originally from Ethiopia) who ruled as regent during the later part of this period, may have influenced the future Fatimids' choice of location for their capital, since one of Kafur's great gardens along the Khalij canal was incorporated into the later Fatimid palaces.[6]

The founding of al-Qahira (Cairo) and the Fatimid period

[edit]

The Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a caliphate which was based in Ifriqiya (Tunisia), conquered Egypt in 969 CE during the reign of Caliph al-Mu'izz. Their army, composed mostly of North African Kutama Berbers, was led by the general Jawhar al-Siqilli. In 970, under instructions from al-Mu'izz, Jawhar planned, founded, and constructed a new city to serve as the residence and center of power for the Fatimid Caliphs. The city was named al-Mu'izziyya al-Qaahirah (Arabic: المعزية القاهرة), the "Victorious City of al-Mu'izz", later simply called "al-Qahira", which gave us the modern name of Cairo.[9]: 80

The city was located northeast of Fustat and of the previous administrative capitals built by Ibn Tulun and the Abbasids. Jawhar organized the new city so that at its center were the Great Palaces that housed the caliphs, their household, and the state's institutions.[6] Two main palaces were completed: an eastern one (the largest of the two) and a western one, between which was an important plaza known as Bayn al-Qasrayn ("Between the Two Palaces"). The city's main mosque, the Mosque of al-Azhar, was founded in 972 as both a Friday mosque and as a center of learning and teaching, and is today considered one of the oldest universities in the world.[3] The city's main street, known today as Al-Mu'izz li-Din Allah Street (or al-Mu'zz street) but historically referred to as the Qasabah or Qasaba, ran from one of the northern city gates (Bab al-Futuh) to the southern gate (Bab Zuweila) and passed between the palaces via Bayn al-Qasrayn. Under the Fatimids, however, Cairo was a royal city which was closed to the common people and inhabited only by the Caliph's family, state officials, army regiments, and other people necessary to the operations of the regime and its city. Fustat remained for some time the main economic and urban center of Egypt. It was only later that Cairo grew to absorb other local cities, including Fustat, but the year 969 is sometimes considered the "founding year" of the current city.[10]

Al-Mu'izz, and with him the administrative apparatus of the Fatimid Caliphate, left his former capital of Mahdia, Tunisia, in 972 and arrived in Cairo in June 973.[9][6] The Fatimid Empire quickly grew powerful enough to stand as a threat to the rival Sunni Abbasid Caliphate. During the reign of Caliph al-Mustansir (1036–1094), the longest of any Muslim ruler, the Fatimid Empire reached its peak but also began its decline.[11] A few strong viziers, acting on behalf of the caliphs, managed to revive the empire's power on occasion. The Armenian vizier Badr al-Jamali (in office from 1073–1094) notably rebuilt the walls of Cairo in stone, with monumental gates, the remains of which still stand today and were expanded under later Ayyubid rule.[6] The late 11th century was also a time of major events and developments in the region. It was at this time that the Great Seljuk (Turkish) Empire took over much of the eastern Islamic world. The arrival of the Turks, who were mainly Sunni Muslims, was a long-term factor in the so-called "Sunni Revival" which reversed the advance of the Fatimids and of Shi'a factions in the Middle East.[12] In 1099 the First Crusade captured Jerusalem, and the new Crusader states became a sudden and serious threat to Egypt. New Muslim rulers such as Nur al-Din of the Turkish Zengid dynasty took charge of the overall offensive against the Crusaders.

In the 12th century the weakness of the Fatimids became so severe that under the last Fatmid Caliph, al-'Adid, they requested help from the Zengids to protect themselves from the King of Jerusalem, Amalric, while at the same time attempting to collude with the latter to keep the Zengids in check.[9] In 1168, as the Crusaders marched on Cairo, the Fatimid vizier Shawar, worried that the unfortified city of Fustat would be used as a base from which to besiege Cairo, ordered its evacuation and then set the city ablaze. While historians debate the extent of the destruction (as Fustat appears to have continued to exist after this), the burning of Fustat nonetheless marks a pivotal moment in the decline of that city, which was later eclipsed by Cairo itself.[6][13] Eventually, Salah ad-Din (Saladin), a Zengid commander who was given the position of al-'Adid's vizier in Cairo, declared the end and dismantlement of the Fatimid Caliphate in 1171. Cairo thus returned to Sunni rule, and a new chapter in the history of Egypt, and of Cairo's urban history, opened.

Cairo's ascendance in the Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

[edit]

Salah ad-Din's reign marked the beginning of the Ayyubid dynasty, which ruled over Egypt and Syria and carried forward the fight against the Crusaders. He also embarked on the construction of an ambitious new fortified Citadel (the current Citadel of Cairo) further south, outside the walled city, which would house Egypt's rulers and state administration for many centuries thereafter. This ended Cairo's status as an exclusive palace-city and started a process by which the city became an economic center inhabited by common Egyptians and open to foreign travelers.[13] Over the subsequent centuries, Cairo developed into a full-scale urban center. The decline of Fustat over the same period paved the way for its ascendance. The Ayyubid sultans and their Mamluk successors, who were Sunni Muslims eager to erase the influence of the Shi'a Fatimids, progressively demolished and replaced the great Fatimid palaces with their own buildings.[6] The Al-Azhar Mosque was converted to a Sunni institution, and today it is the foremost center for the study of the Qur'an and Islamic law in the Sunni Islamic world.[3]

In 1250 the Ayyubid dynasty faltered and power transitioned to a regime controlled by the Mamluks. The mamluks were soldiers who were purchased as young slaves (often from various regions of Central Eurasia) and raised to serve in the army of the sultan. They became a mainstay of the Ayyubid military under Sultan al-Salih and eventually became powerful enough to assume control of the state for themselves in a political crisis during the Seventh Crusade. Between 1250 and 1517, the throne passed from one mamluk to another in a system of succession that was generally non-hereditary, but also frequently violent and chaotic. Nonetheless, the Mamluk Empire continued many aspects of the Ayyubid Empire before it, and was responsible for repelling the advance of the Mongols in 1260 (most famously at the Battle of Ain Jalut) and for putting a final end to the Crusader states in the Levant.[14]

Under the reign of the Mamluk sultan al-Nasir Muhammad (1293–1341, including interregnums), Cairo reached its apogee in terms of population and wealth.[6] A commonly-cited estimate of the population towards the end of his reign, although difficult to evaluate, gives a figure of about 500,000, making Cairo the largest city in the world outside China at the time.[15][16] Despite being a largely military caste, the Mamluks were prolific builders and sponsors of religious and civic buildings. An extensive number of Cairo's historical monuments date from their era, including many of the most impressive.[6][3] The city also prospered from the control of trade routes between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean.[6] After the reign of al-Nasir, however, Egypt and Cairo were struck by repeated epidemics of the plague, starting with the Black Death in the mid-14th century. Cairo's population declined and took centuries to recover, but it remained the major metropolis of the Middle East.[6]

Under the Ayyubids and the later Mamluks, the Qasaba avenue became a privileged site for the construction of religious complexes, royal mausoleums, and commercial establishments, usually sponsored by the sultan or members of the ruling class. This is also where the major souqs of Cairo developed, forming its main economic zone of international trade and commercial activity.[6][3] As the main street became saturated with shops and space for further development there ran out, new commercial structures were built further east, close to al-Azhar Mosque and to the shrine of al-Hussein, where the souq area of Khan al-Khalili, still present today, progressively developed.[13] One important factor in the development of Cairo's urban character was the growing number of waqf establishments, especially during the Mamluk period. Waqfs were charitable trusts under Islamic law which set out the function, operations, and funding sources of the many religious/civic establishments built by the ruling elite. They were typically drawn up to define complex religious or civic buildings which combined various functions (e.g. mosque, madrasa, mausoleum, sebil) and which were often funded with revenues from urban commercial buildings or rural agricultural estates.[17] By the late 15th century Cairo also had high-rise mixed-use buildings (known as a rab', a khan or a wikala, depending on exact function) where the two lower floors were typically for commercial and storage purposes and the multiple stories above them were rented out to tenants.[18]

Cairo as a provincial capital of the Ottoman Empire

[edit]

Egypt was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1517, under Selim I, and remained under Ottoman rule for centuries. During this period, local elites fought ceaselessly among themselves for political power and influence; some of them of Ottoman origin, others from the Mamluk caste which continued to exist as part of the country's elites despite the demise of the Mamluk sultanate.[6]

Cairo continued to be a major economic center and one of the empire's most important cities. It remained the principal staging point for the pilgrimage (Hajj) route to Mecca.[6] While the Ottoman governors were not major patrons of architecture like the Mamluks, Cairo nonetheless continued to develop and new neighbourhoods did grow outside the old city walls.[6][3] Ottoman architecture in Cairo continued to be heavily influenced and derived from the local Mamluk-era traditions rather than presenting a clear break with the past.[3] Some individuals, such as Abd ar-Rahman Katkhuda al-Qazdaghli, a mamluk official among the Janissaries in the 18th century, were prolific architectural patrons.[6][3] Many old bourgeois or aristocratic mansions that have been preserved in Cairo today date from the Ottoman period, as do a number of sabil-kuttabs (a combination of water distribution kiosk and Qur'anic reading school).[3]

Cairo under Muhammad Ali Pasha and the Khedives

[edit]

Napoleon's French army briefly occupied Egypt from 1798 to 1801, after which an Albanian officer in the Ottoman army named Muhammad Ali Pasha made Cairo the capital of an independent empire that lasted from 1805 to 1882. The city then came under British control until Egypt was granted its independence in 1922.

Under Muhammad Ali's rule the Citadel of Cairo was completely refurbished. Many of its disused Mamluk monuments were demolished to make way for his new mosque (the Mosque of Muhammad Ali) and other palaces. Muhammad Ali's dynasty also introduced a more purely Ottoman style of architecture, mainly in the late Ottoman Baroque style of the time.[3] One of his grandsons, Isma'il, as Khedive between 1864 and 1879, oversaw the construction of the modern Suez Canal. Along with this enterprise, he also undertook the construction of a vast new city in European style to the north and west of the historic center of Cairo. The new city emulated Haussman's 19th-century reforms of Paris, with grand boulevards and squares being part of the planning and layout.[6] Although never fully completed to the extent of Isma'il's vision, this new city composes much of Downtown Cairo today. This left the old historic districts of Cairo, including the walled city, relatively neglected. Even the Citadel lost its status as the royal residence when Isma'il moved to the new Abdin Palace in 1874.[3]

Historic sites and monuments

[edit]

Mosques

[edit]While the first mosque in Egypt was the Mosque of Amr ibn al-As in Fustat, the Mosque of Ibn Tulun is the oldest mosque to retain its original form and is a rare example of Abbasid architecture, from the classical period of Islamic civilization. It was built in 876–879 AD in a style inspired by the Abbasid capital of Samarra in Iraq.[3] It is one of the largest mosques in Cairo and is often cited as one of the most beautiful.[3][19]

One of the most important and lasting institutions founded in the Fatimid period was the Mosque of al-Azhar, founded in 970 AD, which competes with the Qarawiyyin in Fes for the title of oldest university in the world.[3] Today, al-Azhar University is the foremost center of Islamic learning in the world and one of Egypt's largest universities with campuses across the country.[3] The mosque itself retains significant Fatimid elements but has been added to and expanded in subsequent centuries, notably by the Mamluk sultans Qaitbay and al-Ghuri and by Abd al-Rahman Katkhuda in the 18th century. Other extant monuments from the Fatimid era include the large Mosque of al-Hakim, the al-Aqmar mosque, Juyushi Mosque, Lulua Mosque, and the Mosque of Salih Tala'i.

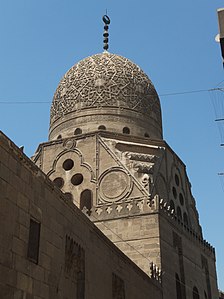

The most prominent architectural heritage of medieval Cairo, however, dates from the Mamluk period, from 1250 to 1517 AD. The Mamluk sultans and elites were eager patrons of religious and scholarly life, commonly building religious or funerary complexes whose functions could include a mosque, madrasa, khanqah (for Sufis), water distribution centers (sabils), and mausoleum for themselves and their families.[17] Among the best-known examples of Mamluk monuments in Cairo are the huge Mosque-Madrasa of Sultan Hasan, the Mosque of Amir al-Maridani, the Mosque of Sultan al-Mu'ayyad (whose twin minarets were built above the gate of Bab Zuwayla), the Sultan Al-Ghuri complex, the funerary complex of Sultan Qaytbay in the Northern Cemetery, and the trio of monuments in the Bayn al-Qasrayn area comprising the complex of Sultan al-Mansur Qalawun, the Madrasa of al-Nasir Muhammad, and the Madrasa of Sultan Barquq. Some mosques include spolia (often columns or capitals) from earlier buildings built by the Romans, Byzantines, or Copts.[3]

Shrines and mausoleums

[edit]Islamic Cairo is also the location of several important religious shrines such as the al-Hussein Mosque (whose shrine is believed to hold the head of Husayn ibn Ali), the Mausoleum of Imam al-Shafi'i (founder of the Shafi'i madhhab, one of the primary schools of thought in Sunni Islamic jurisprudence), the Tomb of Sayyida Ruqayya, the Mosque of Sayyida Nafisa, and others.[3] Some of these shrines are located within the vast cemetery areas known as the City of the Dead or al-Qarafa in Arabic, which adjoin the historic city. The cemeteries date back to the foundation of Fustat, but many of the most prominent and famous mausoleum structures are from the Mamluk era.[20]

Walls and gates

[edit]

City walls

[edit]

When Cairo was founded as a palace-city in 969 by the Fatimid Caliphate, Gawhar al-Siqilli, a Fatimid general, led the construction of the city's original walls out of mudbrick.[21][22] Later, during the late 11th century, the Fatimid vizier Badr al-Gamali ordered a reconstruction of the walls primarily out of stone and further outward than before to expand the space within Cairo's walls.[21] Construction began in 1087.[23] The architectural elements of the walls were informed by Badr al-Gamali's Armenian background, and were innovative in the context of Islamic military architecture in Egypt.[24] The walls are composed of three vertical levels.[24] The lower level was elevated above the street and contained the vestibules of the gates, which were accessible by ramps.[24] The second level contained halls that connected different galleries and rooms.[24] The third level was the terrace level, protected by parapets, where, near gates, belvederes were built for the caliph and his court to use.[24][25] Although it was previously thought that the entirety of Badr al-Gamali's walls were built in stone, more recent archeological findings have confirmed that at least part of the eastern wall was built out of mudbrick, while the gates were built in stone.[26] Since 1999, the preserved northern section of Fatimid walls has been cleared of debris and part of a local urban regeneration.[3]: 244

The founder of the Ayyubid dynasty, Salah ad-Din, restored and/or reconstructed the Fatimid walls and gates in 1170[23] or 1171.[22] He reconstructed parts of the Fatimid walls, including the eastern wall.[23] In 1176, he then began embarked on a project to radically expand the city's fortifications. This project included the construction of the Citadel of Cairo and of a 20 kilometer-long wall to connect and protect both Cairo (referring to the former royal city of the Fatimid caliphs) and Fustat (the main city and earlier capital of Egypt a short distance to the southwest). The entirety of the envisioned course of the wall was never quite completed, but long stretches of the wall were built, including the section to the north of the Citadel and a section near Fustat in south.[27]: 90–91 [28] Al-Maqrizi, a writer from the later Mamluk period, reports several details about the construction. In 1185–6, the wall around Fustat was being built. In 1192, a trench was being built for the eastern fortifications,[27]: 91 by which time some of the eastern wall and its towers were probably in place.[22] Work continued after Salah ad-Din's death under his successors, al-'Adil and al-Kamil. In 1200, orders went out to dig the remaining course of the wall.[27]: 91 More sections of the wall were completed by 1218,[22] but by 1238 work was apparently still ongoing.[27]: 91

Gates

[edit]

Many gates existed along the walls of Fatimid Cairo, but only three remain today: Bab al-Nasr, Bab al-Futuh, and Bab Zuwayla (with "Bab" translating to "gate").[24][28] A restoration project from 2001 to 2003 successfully restored the three gates and parts of the northern wall between Bab al-Nasr and Bab al-Futuh.[21] During the Fatimid period there were many gardens along the walls. A chain of gardens ran past Bab al-Nasr and the garden of al-Mukhtar al-Saqlabi existed outside Bab al-Futuh.[25]

Bab al-Nasr and Bab al-Futuh are both are on the northern section of the wall, about two hundred yards from each other.[28] Bab al-Nasr, which translates to "the Gate of Victory," was originally called Bab al-Izz, meaning "the Gate of Glory," when constructed by Gawhar al-Siqilli. It was reconstructed by Badr al-Gamali between 1087 and 1092 about two hundred meters from the original site and was given its new name.[24][21] Similarly, Bab al-Futuh was originally called Bab al-Iqbal, or "the Gate of Prosperity," and was later renamed Bab al-Futuh by Badr al-Gamali.[21] Bab al-Nasr is flanked by two towers of square shape, with shield insignias carved into the stone, while Bab al-Futuh is flanked by round towers.[21] The vaulted stone ceilings inside Bab al-Nasr are innovative in design, with the helicoidal vaults being the first of their kind in this architectural context.[24] The façade of Bab al-Nasr has a frieze containing Kufic inscriptions in white marble, including a foundation inscription and the Shi'a version of the Shahada which was representative of the Fatimid caliphate's religious beliefs.[28][21][29] Bab al-Futuh features no inscriptions on the gate itself,[28] but an inscription can be seen nearby to the east, on the wall salient around the northern minaret of the al-Hakim Mosque.[3]: 245 Inside Bab al-Futuh, through its eastern flanking doorway, is the tomb of an unidentified figure, and through its western flanking doorway is a long vaulted chamber.[21]

The third surviving gate, Bab Zuwayla, sits in the southern section of the wall.[21] Badr al-Gamali rebuilt the original Bab Zuwayla further south than Gawhar al-Siqilli's original gate.[28] A neighboring mosque, the mosque of al-Mu'ayyad Shaykh, has two minarets that sit on top of the two towers that flank the Bab Zuwayla.[21] Similar to Bab al-Nasr and Bab al-Futuh, Bab Zuwayla was also adjacent to gardens, namely the gardens of Qanṭara al-Kharq.[25]

One of the eastern gates of the city, part of the Ayyubid reconstruction of the walls, was also uncovered in 1998 and subsequently studied and restored. It has a complex defensive layout including a bent entrance and a bridge over a moat or ditch.[22] Initially identified as Bab al-Barqiyya,[22] it is possible that it was actually known as Bab al-Jadid ("New Gate"), one of the three eastern gates mentioned by al-Maqrizi. If so, then the name Bab al-Barqiyya most likely corresponded to another gate a short distance to the northeast.[30] The latter gate, originally discovered in the 1950s,[23] dates from Badr al-Gamali's time and, according to an inscription, was also called Bab al-Tawfiq ("Gate of Success"). It would have replaced the earlier 10th-century Fatimid gate in this area. Archeologists discovered a number of ancient stones with Pharaonic inscriptions that were re-used in the gate's construction.[31][32][3]: 99 It was likely replaced by an Ayyubid-era gate built in front of it, but as of 2008 this had not yet been excavated.[32] Another gate further north, near the northeast corner of the walls, was known as Bab al-Jadid up to the present day and thus possibly contributed to confusion over the identification of the Ayyubid gate uncovered in 1998, with which it shares a similar layout.[30]

Citadel

[edit]Salah ad-Din (Saladin) began the construction of an extensive Citadel in 1176 to serve as Egypt's seat of power, with construction finishing under his successors.[33] It is located on a promontory of the nearby Muqattam Hills overlooking the city. The Citadel remained the residence of the rulers of Egypt until the late 19th century, and was repeatedly transformed under subsequent rulers. Notably, Muhammad Ali Pasha built the 19th-century Mosque of Muhammad Ali which still dominates the city's skyline from its elevated vantage point.[3]

Markets and commercial buildings

[edit]

The Mamluks, and the later Ottomans, also built wikalas (caravanserais; also known as khans) to house merchants and goods due to the important role of trade and commerce in Cairo's economy.[6] The most famous and best-preserved example is the Wikala al-Ghuri, which nowadays also hosts regular performances by the Al-Tannoura Egyptian Heritage Dance Troupe.[34] The famous Khan al-Khalili is a famous souq and commercial hub which also integrated caravanserais.[13] Another example of historic commercial architecture is the 17th-century Qasaba of Radwan Bay, now part of the al-Khayamiyya area whose name comes from the decorative textiles (khayamiyya) still being sold here.[3]

Preservation status

[edit]Much of this historic area suffers from neglect and decay, in this, one of the poorest and most overcrowded areas of the Egyptian capital.[35] In addition, thefts of Islamic monuments and artifacts in the Al-Darb al-Ahmar district threaten their long-term preservation.[36][37][38] In the aftermath of the 2011 uprising theft increased among historic monuments and a lack of zoning enforcement allowed traditional houses to be replaced with high-rise buildings.[3]: 1–2 [39][40] Thefts and illegal constructions have since decreased, but environmental problems remain.[39]

Various efforts to restore historic Cairo have been ongoing in recent decades, with the involvement of both Egyptian government authorities and non-governmental organisations such as the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC).[39] In 1998 the government launched the Historic Cairo Restoration Project (HCRP) which aimed to restore 149 historic monuments.[3]: 2 In the following years numerous restorations were completed under the supervision of the HCRP in the area between Bab Zuweila and Bab Futuh, especially around al-Mu'izz street.[40][3]: 214–258 A restoration of Bay al-Suhaymi and the Darb al-Asfar street in front of it was also completed in 1999 by independent Egyptian conservators with funding from the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development, a Kuwaiti organisation.[3]: 237 By 2010, about 100 of the 149 monuments designated by the HCRP had been restored.[3]: 2 The HCRP has also been criticized, however, for creating an open-air museum geared towards tourists while imparting few benefits on the surrounding community.[40][41] Around the same period, another initiative launched by the AKTC focused on revitalizing the Al-Darb al-Ahmar neighbourhood following the construction of the nearby al-Azhar Park. This project aimed for a more bottom-up approach to improve the community's urban fabric and the socioeconomic situation of residents, as well as involving more public and private participation.[40][41]

Examples of more recent restoration projects include the rehabilitation of the 14th-century Mosque of Amir al-Maridani in Al-Darb al-Ahmar, which began in 2018 and whose first phase was completed in 2021, led in part by the AKTC with additional funding from the European Union.[42][43][39] Between 2009 and 2015 the World Monuments Fund and the AKTC completed a restoration of the 14th-century Mosque of Amir Aqsunqur (also known as the Blue Mosque).[44] Another project completed in 2021 has restored the 18th-century Sabil-kuttab of Ruqayya Dudu in the Suq al-Silah area.[45] In 2021 the Egyptian government began a new push to renovate the old city, including the areas around the historic city gates, partly with the aim to boost tourism. The effort would also involve restoring buildings that are not officially listed as monuments and pedestrianizing some zones. In some cases the owners or tenants of certain buildings have been relocated elsewhere while restoration is ongoing.[46][47][39]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Boundaries and Preservation Codes of Historic Cairo (PDF) (in Arabic). National Organisation for Urban Harmony. 2022.

- ^ "Historic Cairo – Maps". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2023-02-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Williams, Caroline (2018). Islamic Monuments in Cairo: The Practical Guide (7th ed.). Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- ^ Planet, Lonely. "Islamic Cairo in Cairo, Egypt". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ UNESCO, Decision Text, World Heritage Centre, retrieved 21 July 2017

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Raymond, André. 1993. Le Caire. Fayard.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy, Hugh (2007). The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- ^ a b Swelim, Tarek (2015). Ibn Tulun: His Lost City and Great Mosque. The American University in Cairo Press.

- ^ a b c Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Irene Beeson (September–October 1969). "Cairo, a Millennial". Saudi Aramco World. pp. 24, 26–30. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ "Fāṭimid Dynasty | Islamic dynasty". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (1995). The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years. Scribner.

- ^ a b c d Denoix, Sylvie; Depaule, Jean-Charles; Tuchscherer, Michel, eds. (1999). Le Khan al-Khalili et ses environs: Un centre commercial et artisanal au Caire du XIIIe au XXe siècle. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- ^ Clot, André (1996). L'Égypte des Mamelouks: L'empire des esclaves, 1250–1517. Perrin.

- ^ Abu-Lughod, Janet (1971). Cairo: 1001 Years of the City Victorious. Princeton University Press. p. 37.

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (2005). Encyclopedia of African History. Vol. I. Taylor & Francis. p. 342.

- ^ a b Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. 2007. Cairo of the Mamluks: A History of Architecture and its Culture. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- ^ Mortada, Hisham (2003). Traditional Islamic principles of built environment. Routledge. p. viii. ISBN 0-7007-1700-5.

- ^ O'Neill, Zora et al. 2012. Lonely Planet: Egypt (11th edition), p. 87.

- ^ El Kadi, Galila; Bonnamy, Alain (2007). Architecture for the Dead: Cairo's Medieval Necropolis. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Warner, Nicholas (2005). The monuments of historic Cairo : a map and descriptive catalogue. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 977-424-841-4. OCLC 929659618.

- ^ a b c d e f Pradines, Stephane (2002). "La muraille ayyoubide du Caire : les fouilles archéologiques de Bâb al-Barqiyya à Bâb al-Mahrûq". Annales Islamologiques. 36. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale (IFAO): 288.

- ^ a b c d Warner, Nicholas (1999). "The Fatimid and Ayyubid Eastern Walls of Cairo: missing fragments". Annales islamologiques. 33: 283–296.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Salcedo-Galera, Macarena; García-Baño, Ricardo (2022-09-01). "Stonecutting and Early Stereotomy in the Fatimid Walls of Cairo". Nexus Network Journal. 24 (3): 657–672. doi:10.1007/s00004-022-00611-1. hdl:10317/12232. ISSN 1522-4600.

- ^ a b c Pradines, Stephane; Khan, Sher Rahmat (October 2016). "Fāṭimid gardens: archaeological and historical perspectives". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 79 (3): 473–502. doi:10.1017/S0041977X16000586. ISSN 0041-977X.

- ^ Pradines, Stephane (2008). "Bab al-Tawfiq: une porte du Caire fatimide oubliée par l'histoire". Le Muséon. 121 (1–2): 143–170.

- ^ a b c d Raymond, André (2000) [1993]. Cairo. Translated by Wood, Willard. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00316-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Kay, H. C. (1882). "Al Kāhirah and Its Gates". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 14 (3): 229–245. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00018232. ISSN 0035-869X. JSTOR 25196925. S2CID 164159559.

- ^ Shalem, Avinoam (1996). "A Note on the Shield-Shaped Ornamental Bosses on the Façade of Bāb al-Nasr in Cairo". Ars Orientalis. 26: 55–64. ISSN 0571-1371. JSTOR 4629499.

- ^ a b Pradines, Stephane (2008). "Bab al-Tawfiq: une porte du Caire fatimide oubliée par l'histoire". Le Muséon. 121 (1–2): 143–170.

- ^ Régen, Isabelle; Postel, Lilian (2005). "Annales héliopolitaines et fragments de Sésostris I réemployés dans la porte de Bâb al-Tawfiq au Caire". Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale (IFAO). 105: 229–293.

- ^ a b Pradines, Stephane (2008). "Bab al-Tawfiq: une porte du Caire fatimide oubliée par l'histoire". Le Muséon. 121 (1–2): 143–170.

- ^ Rabat, Nasser O. (1995). The Citadel of Cairo: A New Interpretation of Royal Mamluk Architecture. E.J. Brill.

- ^ O'Neill, Zora et al. 2012. Lonely Planet: Egypt (11th edition), p. 81.

- ^ Ancient Cairo: Preserving a Historical Heritage, Qantara, 2006.

- ^ Unholy Thefts Archived 2013-06-05 at the Wayback Machine Al-Ahram Weekly, Nevine El-Aref, 26 June – 2 July 2008 Issue No. 903.

- ^ "Al-Darb Al-Ahmar District Mosques". World Monuments Fund.

- ^ Wilton-Steer, Harry Johnstone, photography by Christopher (March 21, 2018). "Alive with artisans: Cairo's al-Darb al-Ahmar district – a photo essay". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e "Egypt struggles to restore historic Cairo's glory". MEO. 2018-06-11. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ a b c d Wessling, Christoph (2017). "Revitalization of Old Cairo". In Abouelfadl, Hebatalla; ElKerdany, Dalila; Wessling, Christoph (eds.). Revitalizing City Districts: Transformation Partnership for Urban Design and Architecture in Historic City Districts. Springer. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-3-319-46289-9.

- ^ a b Bakhoum, Dina Ishak (2018). "Implementing the World Heritage Sustainable Development Policy in Egypt: An opportunity for collective engagement in heritage conservation". In Larsen, Peter Bille; Logan, William (eds.). World Heritage and Sustainable Development: New Directions in World Heritage Management. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-60888-6.

- ^ "Al-Tunbagha Al-Maridani Mosque restored - Heritage - Al-Ahram Weekly". Ahram Online. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Glories of Cairo's medieval past revealed - Spotlight - AKDN". the.akdn. Archived from the original on 2022-10-31. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Jama'a Al -Aqsunqur (Blue Mosque)". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Rescuing our monuments: Restoration in Islamic Cairo - Heritage - Al-Ahram Weekly". Ahram Online. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ "Historic Cairo regains its ancient glory - Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com. December 2021. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

- ^ Werr, Patrick (2021-09-29). "Egypt forges new plan to restore Cairo's historic heart". Reuters. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

External links

[edit] Media related to Islamic Cairo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Islamic Cairo at Wikimedia Commons Islamic Cairo travel guide from Wikivoyage

Islamic Cairo travel guide from Wikivoyage