Bariatric surgery

It has been suggested that Stomach reduction surgery be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2024. |

| Bariatric surgery | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Weight loss surgery |

| MeSH | D050110 |

| Part of a series on |

| Human body weight |

|---|

Bariatric surgery (also known as metabolic surgery or weight loss surgery) is a surgical procedure used to manage obesity and obesity-related conditions.[1][2] Long term weight loss with bariatric surgery may be achieved through alteration of gut hormones, physical reduction of stomach size, reduction of nutrient absorption, or a combination of these.[2][3] Standard of care procedures include Roux en-Y bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, from which weight loss is largely achieved by altering gut hormone levels responsible for hunger and satiety, leading to a new hormonal weight set point.[3]

In morbidly obese people, bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for weight loss and reducing complications.[4][5][6][7][8] A 2021 meta-analysis found that bariatric surgery was associated with reduction in all-cause mortality among obese adults with or without type 2 diabetes.[9] This meta-analysis also found that median life-expectancy was 9.3 years longer for obese adults with diabetes who received bariatric surgery as compared to routine (non-surgical) care, whereas the life expectancy gain was 5.1 years longer for obese adults without diabetes.[9] The risk of death in the period following surgery is less than 1 in 1,000.[10] A 2016 review estimated bariatric surgery could reduce all-cause mortality by 30-50% in obese people.[1] Bariatric surgery may also lower disease risk, including improvement in cardiovascular disease risk factors, fatty liver disease, and diabetes management.[11]

As of October 2022,[update] the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity recommended consideration of bariatric surgery for adults meeting two specific criteria: people with a body mass index (BMI) of more than 35 whether or not they have an obesity-associated condition, and people with a BMI of 30–35 who have metabolic syndrome.[11][12] However, these designated BMI ranges do not hold the same meaning in particular populations, such as among Asian individuals, for whom bariatric surgery may be considered when a BMI is more than 27.5.[11] Similarly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends bariatric surgery for adolescents 13 and older with a BMI greater than 120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex.[13]

Medical uses

[edit]Bariatric surgery has proven to be the most effective obesity treatment option for enduring weight loss.[14] Along with this weight reduction, the procedure reduces risk of cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, depression syndromes, among others.[15] While often effective, numerous barriers to shared decision making between the medical provider and person affected include lack of insurance coverage or understanding how it functions, a lack of knowledge about procedures, conflicts with organizational priorities and care coordination, and tools supporting people who need the surgery.[16]

Eligibility and guidelines

[edit]Historically, eligibility for bariatric surgery was defined as a BMI greater than 40, or a BMI more than 35 with an obesity-associated comorbidity, as based on the 1991 NIH Consensus Statement.[11] In the three decades that followed, obesity rates continued to rise, laparoscopic surgical techniques made the procedure safer, and high-quality research showed effectiveness at improving health among various conditions.[12] In October 2022, ASMBS/IFSO revised the eligibility criteria, which include all adult patients with BMI greater than 35, and those with BMI more than 30 with metabolic syndrome.[12] However, BMI is a limited measurement, for which factors such as ethnicity are not used in the BMI calculation. Eligibility criteria for bariatric surgery is modified for people who identify as a part of the Asian population to a BMI more than 27.5.[11]

As of 2019,[update] the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended bariatric surgery without age-based eligibility limits under the following indications: BMI more than 35 with severe comorbidity, such as obstructive sleep apnea (Apnea-Hypopnea Index above 0.5), type 2 diabetes, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Blount disease, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and idiopathic hypertension or a BMI above 40 without comorbidities.[17] Surgery is contraindicated with a medically correctable cause of obesity, substance abuse, concurrent or planned pregnancy, eating disorder, or inability to adhere to postoperative recommendations and mandatory lifestyle changes.[17]

When counseling a patient on bariatric procedures, providers take an interdisciplinary approach. Psychiatric screening is also critical for determining postoperative success.[18][19] People with a BMI of 40 or greater have a 5-fold risk of depression, and half of bariatric surgery candidates are depressed.[18][19] Among bariatric surgery candidates and those who undergo bariatric surgery, mental health-related conditions including anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and substance use are also more commonly reported.[20]

Weight loss

[edit]In adults, malabsorptive procedures lead to more weight loss than restrictive procedures, but they have a higher risk profile.[21] Gastric banding is the least invasive, so it may offer fewer complications, while gastric bypass may offer the highest initial and most sustainable weight loss.[21] A single protocol has not been found to be superior to the other. In one 2019 systematic review, estimated weight loss (EWL) for each surgical protocol is as follows: 56.7% for gastric bypass, 45.9% for gastric banding, 74.1% for biliopancreatic bypass +/- duodenal switch and 58.3% for sleeve gastrectomy.[22] Most patients do remain obese (BMI 25-35) following surgery despite significant weight loss, and patients with BMI over 40 tended to lose more weight than those with BMI under 40.[23][24]

With regard to metabolic syndrome, bariatric surgery patients were able to achieve remission 2.4 times as often as those who underwent nonsurgical treatment.[25][23] No significant difference was noted for changes cholesterol, or LDL, but HDL did increase in the surgical groups, and reduction in blood pressure was variable between studies.[25][23]

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

[edit]Studies of bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes (T2DM) within the obese population show that 58% prioritize improvement of diabetes, while 33% pursued surgery for weight loss alone.[26] While weight loss is essential in T2DM management, sustaining improvements long-term is challenging; 50% to 90% of people struggle to achieve adequate diabetes control, suggesting the need for alternative interventions.[27][28] In this context, studies have reported an 85.3–90% resolution of T2DM after bariatric surgery, measured by reductions in fasting plasma glucose and HbA1C levels, and remission rates of up to 74% two years post-surgery.[27][28] Furthermore, there is a difference in effectiveness between bariatric surgery and traditional interventions. The Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study demonstrated the difference in T2DM remission rates between conventional medical therapy and bariatric surgery: while conventional methods achieved a 21% remission at two years and 12% at 10 years, bariatric surgery exhibited a 72% remission at two years and 37% at 10 years.[28]

The relative risk reductions associated with bariatric surgery are 61%, 64%, and 77% for the development of T2DM, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, respectively, highlighting the efficacy of bariatric surgery in prevention as well as resolution of chronic obesity.[24] Predictors for post-operative diabetes resolution include current method of diabetes control, adequate blood sugar control, age, duration of diabetes, and waist circumference.[26]

Bariatric surgery likewise plays a role in the reduction of medication use.[27][24] During post-operative follow-up, 76% of people discontinued use of insulin, while 62% no longer required T2DM medications at all.[27][24]

Bariatric surgery is also considered for individuals with new-onset T2DM and obesity, although the level of improvement may be slightly less.[28][24][27] The International Diabetes Federation Task recommends bariatric surgery under certain circumstances, including failure of conventional weight and T2DM therapy in individuals with a BMI of 30–35.[28] The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, however, maintain their recommendation of bariatric surgery for only those of BMI above 35.[28]

Reduced mortality and morbidity

[edit]A 2021 meta-analysis found that bariatric surgery was associated with 59% and 30% reductions in all-cause mortality among obese adults with or without type 2 diabetes respectively.[9] It also found that median life-expectancy was 9 years longer for obese adults with diabetes who received bariatric surgery as compared to routine (non-surgical) care, whereas the life expectancy gain was 5 years longer for obese adults without diabetes.[9] The overall cancer risk in bariatric surgery patients was decreased by 44%, especially in colorectal, endometrial, breast, and ovarian cancer.[29] Improvements in cardiovascular health are the most well described changes after bariatric surgery, with notable reductions in the incidence of stroke (except in patients with T2DM), heart attack, atrial fibrillation, all-cause cardiovascular mortality, and ischemic heart disease.[29][24]

Bariatric surgery in older patients is a safety concern; the relative benefits and risks in this population are not known.[30]

Fertility and pregnancy

[edit]The position of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery as of 2017[update] was that it was not clearly understood whether medical weight-loss treatments or bariatric surgery had an effect responsiveness to subsequent treatments for infertility in both men and women.[31] Bariatric surgery reduces the risk of gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in women who later become pregnant, but increases the risk of preterm birth, and maternal anemia.[29][32] For women with PCOS, post-operatively there tends to be a reduction in menstrual irregularity, hirsutism, infertility, and the overall prevalence of PCOS is reduced at 12 and 23 months.[29]

Mental health

[edit]Among people seeking bariatric surgery, pre-operative mental health disorders are commonly reported.[33][20] Some studies indicate that psychological health can improve after bariatric surgery, due in part to improved body image, self-esteem, and change in self-concept; these findings were found in children (see Considerations in adolescent patients below).[34] Bariatric surgery has consistently been associated with postoperative decreases in depression symptoms and reduced severity.[34]

Risks and complications

[edit]Weight loss surgery in adults is associated with an elevated risk of complications compared to nonsurgical treatments for obesity.[35]

The overall risk of mortality is low in bariatric surgery at 0 to .01%. Severe complications, such as gastric perforation or necrosis, have been significantly reduced by improved surgical experience and training. Bariatric surgery morbidity is also low at 5%.[21][25][29] In fact, several studies have reported a reduced overall long-term all-cause mortality compared to controls.[21][25][29] However, obese populations maintain an elevated risk of disease and mortality compared to the general population even after surgery, therefore elevated mortality after surgery may be related to the ongoing complications of existing obesity-related disease.[21][25][29]

The percentage of procedures requiring reoperations due to complications was 8% for adjustable gastric banding, 6% after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, 1% for sleeve gastrectomy, and 5% after biliopancreatic diversion.[23] Over a 10-year study while using a common data model to allow for comparisons, 9% of patients who received a sleeve gastrectomy required some form of reoperation within 5 years compared to 12% of patients who received a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Both of the effects were fewer than those reported with adjustable gastric banding.[36]

Postoperative

[edit]Laparoscopic bariatric surgery requires an average hospital stay of 2–5 days, barring potential complications.[37] Minimally invasive procedures (i.e. adjustable gastric band) tend to have less complications than open procedures (i.e. Roux-en-Y).[21][29] Similar to other surgical procedures, there is a risk of atelectasis (collapse of small airways) and pleural effusion (fluid buildup in lungs), and pneumonia which tends to be less associated with minimally invasive procedures.[21][29]

Complications specific to the laparoscopic gastric band procedure include esophageal perforation from advancement of the calibration probe, gastric perforation from creation of a retrograde gastric tunnel, esophageal dilation, and acute dilation of the gastric pouch due to malpositioning of the gastric band.[21] Gastric band malpositioning can be devastating, leading to gastric prolapse, overdistention, and resultingly, gastric ischemia and necrosis.[21] Erosion and migration of the band may also occur post-operatively, in which case, if over 50% of the circumference of the band migrates, then surgical repositioning is necessary.[21]

Risks of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass include anastomotic stenosis (narrowing of the intestine where the two segments are rejoined), bleeding, leaks, fistula formation, ulcers (ulcers near the rejoined segment), internal hernia, small bowel obstruction, kidney stones, and gallstones.[21] Bowel obstruction tends to be more difficult to diagnose in post-bariatric surgery patients due to their reduced ability to vomit; symptoms mainly involve abdominal pain and are intermittent due to twisting and untwisting of the intestinal mesentery.[21]

Sleeve gastrectomy also carries a small risk of stenosis, staple line leak, stricture formation, leaks, fistula formation, bleeding and gastro-esophageal reflux disease (also known as GERD, or heartburn).[15][21]

Deficiencies of micronutrients like iron (15%), vitamin D, vitamin B12, fat soluble vitamins, thiamine, and folate are common after bariatric procedures.[21][23] Such deficiencies are potentiated by alterations in absorption and lack of appetite and often require supplementation. Notably, chronic vitamin D deficiency may contribute to osteoporosis; insufficiency fractures, especially of the upper extremity, are of higher incidence in bariatric surgery patients.[21][29] Sleeve gastrectomy leads to fewer long-term vitamin deficiencies compared to gastric banding.

Gastrointestinal

[edit]The most common complication, especially after sleeve gastrectomy, is GERD, which may occur in up to 25% of cases.[38] Dumping syndrome (rapid emptying of undigested stomach contents) is another common complication of bariatric surgery, especially after Roux-en-Y, which is further classified into early and late dumping syndrome.[38] Dumping syndrome in some cases may be associate with more efficient weight loss, however it can be uncomfortable.[38] Symptoms of dumping syndrome include nausea, diarrhea, painful abdominal cramps, bloating, and autonomic symptoms such as tachycardia, palpitations, flushing, and sweating.[38] Early dumping syndrome (emptying within 1 hour of eating) is also associated with a rapid drop in blood pressure, which may cause fainting.[38] Late dumping syndrome is characterized by low blood sugar 1–3 hours after a meal, presenting with palpitations, tremor, sweating, a feeling of faintness, and irritability.[38] Dumping syndrome is best mitigated by consuming small meals and avoiding high carb or high fat foods.[38]

Gallstones

[edit]Rapid weight loss after obesity surgery can contribute to the development of gallstones, especially at 6 and 18 months.[21][23] Estimates for prevalence of symptomatic gallstones after Roux-En-Y gastric bypass range from 3–13%.[15] The risk of gallstones following bariatric surgery has shown to be higher among those of the female sex.[39]

Kidney stones

[edit]Kidney stones are common after Roux-En-Y gastric bypass, with estimates of prevalence ranging from 7-11%.[15] All surgical modalities are associated with a significant increase in risk of kidney stones compared to nonsurgical weight loss treatment, with biliopancreatic diversion being the most associated at a ten-fold increase in one study.[40]

Micronutrient malnutrition

[edit]Bariatric surgery as a treatment for obesity can lead to vitamin deficiencies. Long-term follow-up reported deficiencies for vitamins D, E, A, K and B12.[41] There are guidelines for multivitamin supplementation, but adherence rates are reported to be less than 20%.[42]

Pregnancy

[edit]Pregnancy in patients post-bariatric surgery must be carefully monitored. Infant mortality, preterm birth, small fetal size, congenital anomalies, and NICU admission are all elevated in bariatric surgery patients. This elevation in adverse outcomes is thought to be because of malnutrition.[43] Most notably, a reduction in serum folate and iron are well-established correlates to neural tube defects and preterm birth, respectively. People considering pregnancy should consult with their physician before conceiving to optimize their health and nutritional status before pregnancy.[43]

Technique

[edit]Mechanisms of action

[edit]Bariatric procedures function by a variety of mechanisms, such as: alteration of gut hormones, reduction of the gut size (reducing the amount of food that may pass through), and reduction or blockage of nutrient absorption.[2][44] The distinction in these mechanisms, and which are at work for a particular bariatric procedure is not always clearly defined, as multiple mechanisms may be used by a single procedure.[2][3] For instance, while sleeve gastrectomy (discussed below) was initially thought to work simply by reducing the size of the stomach, research has begun to elucidate changes in gut hormone signaling as well.[15] The two most frequently performed procedures are sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (also galled gastric bypass), with sleeve gastrectomy accounting for more than half of all procedures since 2014.[15]

Hormone regulation

[edit]Studies have shown that bariatric procedures may have additional affects on the hormones that affect hunger and satiety (such as ghrelin and leptin), despite initial development to target reduction of food intake and/or nutrient absorption.[2][15][45] This is especially important when considering the durability of weight loss compared to lifestyle changes. While diet and exercise are essential for maintaining a healthy weight and physical fitness, metabolism typically slows as the individual loses weight, a process known as metabolic adaptation.[45] Thus, efforts for obese individuals to lose weight often stall, or result in weight re-gain. Bariatric surgery is thought to affect the weight "set point," leading to a more durable weight loss. This is not completely understood, but may involve the cell-signaling pathways and hunger/satiety hormones.[3]

Restricting food intake

[edit]Procedures may reduce food intake by reducing the size of the stomach that is available to hold a meal (see below: gastric sleeve or stomach folding). Filling the stomach faster enables an individual to feel more full after a smaller meal.[2][3][46]

Nutrient absorption

[edit]Procedures may reduce the amount of intestine that food passes through in an effort to decrease the absorption of nutrients from food.[2][3] For example, a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass connects the stomach to a more distal part of the intestine, which reduces the ability of the intestines to absorb nutrients from the food.[3]

Most common techniques

[edit]

Sleeve gastrectomy

[edit]Sleeve gastrectomy, also known as a gastric sleeve, is a surgical weight-loss procedure where the stomach size is reduced by the surgical removal of a large portion of the stomach, following along the major curve of the stomach.[2] The open edges are then attached together (typically with surgical staples, sutures, or both) to leave the stomach shaped more like a tube, or a sleeve, with a banana shape.[15]

The procedure is performed laparoscopically and is not reversible. It has been found to produce a weight loss comparable to that of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.[15] The risk of ulcers or narrowing of the gut due to intestinal strictures is less so with sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, but it is not as effective at treating GERD or type 2 diabetes.[15]

This was the most commonly performed bariatric surgery as of 2021[update] in the United States, and is one of the two most commonly performed bariatric surgeries in the world.[2][3] Though initially thought to work strictly by reducing the size of the stomach, recent research has shown that there are also changes in gut signaling hormones with this procedure leading to weight loss.[2][46]

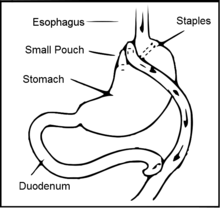

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery

[edit]

Main article: Gastric bypass surgery

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery involves the creation of a new connection in the gastrointestinal tract, from a smaller portion of the stomach to the middle of the small intestine.[3]

The surgery is a permanent procedure that aims to decrease the absorption of nutrients due to the new, limited connection created.[3] The surgery is also works by affecting gut hormones, resetting hunger and satiety levels.[3] The physically-smaller stomach and increase in baseline satiety hormones help people to feel full with less food after the surgery.[3]

This is most commonly performed operation for weight loss in the United States, with approximately 140,000 gastric bypass procedures performed in 2005.[15] A 2021 evidence update comparing the benefits and harms of bariatric procedures found that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and sleeve gastrectomy both effectively reduce weight and led to Type 2 diabetes remission. After five years, Roux-en-Y resulted in greater weight loss (26% compared to 19% for sleeve gastrectomy) and a 25% lower rate of diabetes relapse. However, Roux-en-Y patients had a higher likelihood of hospitalization and additional abdominal surgeries compared to sleeve gastrectomy.[47] Though, since 2013, sleeve gastrectomy has overtaken RYGB as the most common bariatric procedure.[15] RYGB still remains to be one of the two most commonly performed bariatric surgeries in the world.[2][3]

Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch

[edit]

Main Article: biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch

The biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) is a slightly less common bariatric procedure, but is increasing in use with proven efficacy for sustainable weight loss.[48]

This procedure has multiple steps. First, a sleeve gastrectomy (see above section) is performed. This part of the procedure causes food intake restriction due to the physical reduction of the stomach size, and is permanent.[48] Next, the stomach is then disconnected from the upper part of the small intestine and connected to a farther part of the small intestine (ileum), creating the alimentary limb.[48] The leftover section of the far part of the small intestine is then used to make a connection that brings digestive fluids from the gallbladder and pancreas to the alimentary limb.[48]

Weight loss following the surgery is largely due to alteration of gut hormones that control hunger and satiety, as well as the physical restriction of the stomach and decrease in nutrient absorption.[49] Compared to the sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, BPD/DS produces better results with lasting weight loss and resolution of type 2 diabetes.[49]

Other related bariatric procedures

[edit]

Vertical banded gastroplasty

[edit]Vertical banded gastroplasty was more commonly used in the 1980s, and is not typically performed in the 21st century.[51]

In the vertical banded gastroplasty, a part of the stomach is permanently stapled to create a smaller, new stomach.[51] This new stomach is physically restricted, allowing for people to feel full with smaller meals.[52] Short term weight loss is similar to other bariatric procedures, but long-term complications may be higher.[52]

Gastric plication

[edit]This procedure is similar to the sleeve gastrectomy surgery, but a sleeve is created by suturing, rather than physically removing stomach tissue.[53] This allows for the natural ability of the stomach to absorb nutrients to remain intact.[53] This procedure is reversible, is a less invasive procedure, and does not use hardware or staples.[54]

Gastric plication significantly reduces the volume of the patient's stomach, so smaller amounts of food provide a feeling of satiety.[54] In a 2020 review and meta-analysis, long-term weight loss was not as durable as other, more common bariatric techniques.[54] Gastric plication has not performed as well as the sleeve gastrectomy, with the sleeve gastrectomy associated with greater weight loss and fewer complications.[53]

Implants and devices

[edit]Adjustable gastric band

[edit]

The restriction of the stomach also can be created using a silicone band, which can be adjusted by addition or removal of saline through a port placed just under the skin, a procedure called adjustable gastric band surgery.[30] This operation can be performed laparoscopically, and is commonly referred to as a "lap band". Weight loss is predominantly due to the restriction of nutrient intake that is created by the small gastric pouch and the narrow outlet.[30] It is considered somewhat of a safe surgical procedure, with a mortality rate of 0.05%.[30]

Intragastric balloon

[edit]Intragastric balloon involves placing a deflated balloon into the stomach, and then filling it to decrease the amount of gastric space, resulting in the feeling of fullness after a smaller meal.[55][56] The balloon can be left in the stomach for a maximum of 6 months and results in weight loss of 3 BMI or 3–8 kg within several study ranges.[55][56] Weight loss with the gastric balloon tends to be more modest than other interventions. The intragastric balloon may be used prior to another bariatric surgery to assist the patient to reach a weight which is suitable for surgery, but can be used repeatedly and unrelated to other procedures.[56]

Implantable gastric stimulation

[edit]This procedure where a device similar to a heart pacemaker that is implanted by a surgeon, with the electrical leads stimulating the external surface of the stomach, was under preliminary research in 2015.[57] Electrical stimulation is thought to modify the activity of the enteric nervous system of the stomach, which is interpreted by the brain to give a sense of satiety, or fullness. Early evidence suggests that it is less effective than other forms of bariatric surgery.[57]

Recovery

[edit]People are followed closely both before and after bariatric procedures by a healthcare team. The care team may include people in a variety of disciplines, such as social workers, dietitians, and medical weight management specialists.[30] Follow-up after surgery is typically focused on helping avoid complications and tracking the progress toward body weight goals.[30] Having a structure of social support in the post-operative time may be beneficial as people work through the changes that present physically and emotionally following surgery.[20]

Dietary recommendations

[edit]Dietary restrictions after recovery from surgery depend in part on the type of surgery. In general, immediately after bariatric surgery, the person is restricted to a clear liquid diet, which includes foods such as broth, diluted fruit juices or sugar-free drinks.[58] This diet is continued until the gastrointestinal tract begins to recover approximately 2–3 weeks after surgery.[58] The next stage provides a puréed liquid or soft-solid diet that is slightly increased in viscosity. This may consist of high protein, liquid or soft foods such as protein shakes, soft meats and dairy products.[30][58] People in recovery are encouraged to compose their diet mainly of plant-based foods and soft proteins (1.0–1.5g/kg/day).[30][58] During recovery, people must adapt to eating more slowly and to avoid eating past fullness; overeating may lead to nausea and vomiting.[30][58] Alcohol is avoided completely in the first 6 months to 1 year after surgery.[58] Some people may take a daily multivitamin to compensate for reduced absorption of essential nutrients.[30]

Fertility and family planning

[edit]In general, women are advised to avoid pregnancy for 12–24 months after a bariatric surgery to reduce the possibility of intrauterine growth restriction or nutrient deficiency, since a person having bariatric surgery will likely undergo significant weight loss and changes in metabolism. Over many years, the rates of potential adverse maternal and fetal outcomes are reduced for mothers following bariatric surgery.[29][32][58]

Post-operative bariatric plastic surgery

[edit]After a person successfully loses weight following bariatric surgery, excess skin may occur.[59] Bariatric plastic surgery procedures, sometimes called body contouring, may be an option for people wishing to remove excess skin following the large change in weight.[60] Targeted areas include the arms, buttocks and thighs, abdomen, and breasts, with changes occurring slowly over years.[61]

History

[edit]Techniques for weight loss have been reported for decades, with a more formal transition to noting weight loss following surgical intervention in the 1950s when subsequent weight loss after surgical shortening of the small intestine in dogs and people was observed.[62][63] Specifically, anastomosis between upper and lower portions of the small intestine to skip, or bypass, part of the small intestine led to what was called the jejuno-ileal bypass.[63] A modified version of this procedure showed long-term improvement of lipid levels in people with known high levels of cholesterol following the procedure.[63]

Further modification of the bypass procedure achieved weight loss in obesity, during which an anastomosis between the small intestine and upper lower intestine, known as a jejunocolic bypass, was performed.[62] During the late 1960s, the initiation of bariatric surgery followed development of a procedure to bypass portions of the stomach – the gastric bypass.[62][63]

Society and culture

[edit]Economic implications

[edit]In the 21st century, obesity rates increased globally, and with this, a proportional rise in related diseases and complication.[15][64] In the United States during 2017-20, an estimated 40% of adults were obese, up from 30% in 1999-2000.[15] The costs of treating obesity and related conditions has a large economic impact globally.[65][66] This economic impact results from direct treatment of obesity, treatment of obesity-related conditions, as well as other economic losses from decreased workforce productivity.[15][66]

Bariatric surgery is cost-effective when compared to savings estimated from treatment or prevention of obesity-related conditions.[66] Cost-effectiveness occurs at the individual level due to fewer healthcare expenses for medications, and nationally with a reduction in the overall lifetime healthcare costs.[67][66]

Special populations

[edit]Adolescents

[edit]During the early 21st century, obesity among children and adolescents increased globally, as did treatment options including lifestyle changes, drug treatments, and surgical procedures.[68][69] The medical complications and health concerns associated with childhood obesity may have short or long-term effects, with a growing concern of a potential decline in overall life expectancy.[69][70] Childhood obesity may affect mental health and impact eating practices.[69]

Difficulties surrounding obesity treatment selection among children and adolescents include ethical considerations when obtaining consent from those who may be unable to do so without adult guidance or understand the potential lasting effects of invasive procedures.[68][71] Among high-quality randomized control trial data for surgical treatment of obesity, many studies are not specific to children and adolescents.[72] Concerns for bullying about overweight or body image exist for those with childhood obesity; self-harm among children and adolescents bullied for their weight also occurs.[69]

Bariatric surgical procedures available to adolescents include: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, vertical sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric banding.[73] Multiple organizations have created guidelines for bariatric surgery indications in children and adolescents. In 2022-23, such guidelines overlapped with recommendations for potential bariatric surgical management in children and adolescents with a BMI of 40 or higher, or a BMI of 35 or higher while also experiencing related experiences.[74][11][75]

Reviews have shown similar weight loss in adolescents following bariatric surgery as in adults.[76] Reduction of eating disorders for several years after bariatric surgery has also been shown in adolescents after bariatric surgery.[76] Long-term reduction in or resolution of weight-related conditions, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, occurred in adolescents after bariatric surgery.[77] Long-term effects of bariatric surgery in adolescents remains under research, as of 2023.[76][77]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Schroeder R, Harrison TD, McGraw SL (January 2016). "Treatment of Adult Obesity with Bariatric Surgery". American Family Physician. 93 (1): 31–37. PMID 26760838.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Rogers AM (March 2020). "Current State of Bariatric Surgery: Procedures, Data, and Patient Management". Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 23 (1): 100654. doi:10.1016/j.tvir.2020.100654. PMID 32192634. S2CID 213191179.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Pucci A, Batterham RL (February 2019). "Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: similar, yet different". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 42 (2): 117–128. doi:10.1007/s40618-018-0892-2. PMC 6394763. PMID 29730732.

- ^ Müller TD, Blüher M, Tschöp MH, DiMarchi RD (March 2022). "Anti-obesity drug discovery: advances and challenges". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 21 (3): 201–223. doi:10.1038/s41573-021-00337-8. PMC 8609996. PMID 34815532.

Bariatric surgery represents the most effective approach to weight loss

- ^ Bettini S, Belligoli A, Fabris R, Busetto L (September 2020). "Diet approach before and after bariatric surgery". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 21 (3): 297–306. doi:10.1007/s11154-020-09571-8. PMC 7455579. PMID 32734395.

- ^ Zarshenas N, Tapsell LC, Neale EP, Batterham M, Talbot ML (May 2020). "The Relationship Between Bariatric Surgery and Diet Quality: a Systematic Review". Obesity Surgery. 30 (5): 1768–1792. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04392-9. PMID 31940138. S2CID 210195296.

Bariatric surgery is currently the most effective treatment for morbid obesity.

- ^ Hedjoudje A, Abu Dayyeh BK, Cheskin LJ, Adam A, Neto MG, Badurdeen D, et al. (May 2020). "Efficacy and Safety of Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 18 (5): 1043–1053.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.022. PMID 31442601. S2CID 201632114.

- ^ Snoek KM, Steegers-Theunissen RP, Hazebroek EJ, Willemsen SP, Galjaard S, Laven JS, et al. (October 2021). "The effects of bariatric surgery on periconception maternal health: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Reproduction Update. 27 (6): 1030–1055. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmab022. PMC 8542997. PMID 34387675.

Worldwide, the prevalence of obesity in women of reproductive age is increasing. Bariatric surgery is currently viewed as the most effective, long-term solution for this problem

- ^ a b c d Syn NL, Cummings DE, Wang LZ, Lin DJ, Zhao JJ, Loh M, et al. (May 2021). "Association of metabolic-bariatric surgery with long-term survival in adults with and without diabetes: a one-stage meta-analysis of matched cohort and prospective controlled studies with 174 772 participants". Lancet. 397 (10287): 1830–1841. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00591-2. PMID 33965067. S2CID 234345414.

- ^ Robertson AG, Wiggins T, Robertson FP, Huppler L, Doleman B, Harrison EM, et al. (August 2021). "Perioperative mortality in bariatric surgery: meta-analysis". The British Journal of Surgery. 108 (8): 892–897. doi:10.1093/bjs/znab245. hdl:20.500.11820/24849bd8-665f-406f-aac2-b8b1fc0fbb16. PMID 34297806.

- ^ a b c d e f Eisenberg D, Shikora SA, Aarts E, Aminian A, Angrisani L, Cohen RV, et al. (December 2022). "2022 American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO): Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 18 (12): 1345–1356. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2022.08.013. PMID 36280539. S2CID 253077054.

- ^ a b c "After 30 Years — New Guidelines For Weight-Loss Surgery". American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. 2022-10-21. Retrieved 2022-11-07.

- ^ "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity". American Academy of Pediatrics. February 2023. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, Smith VA, Yancy WS, Weidenbacher HJ, et al. (November 2016). "Bariatric Surgery and Long-term Durability of Weight Loss". JAMA Surgery. 151 (11): 1046–1055. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2317. PMC 5112115. PMID 27579793.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o English WJ, Williams DB (July 2018). "Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: An Effective Treatment Option for Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease". Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 61 (2): 253–269. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2018.06.003. PMID 29953878. S2CID 49592181.

- ^ Arterburn D, Tuzzio L, Anau J, Lewis CC, Williams N, Courcoulas A, et al. (February 2023). "Identifying barriers to shared decision-making about bariatric surgery in two large health systems". Obesity. 31 (2): 565–573. doi:10.1002/oby.23647. PMID 36635226. S2CID 255773525.

- ^ a b Armstrong SC, Bolling CF, Michalsky MP, Reichard KW (December 2019). "Pediatric Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: Evidence, Barriers, and Best Practices". Pediatrics. 144 (6): e20193223. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3223. PMID 31656225. S2CID 204947687.

- ^ a b Yen YC, Huang CK, Tai CM (September 2014). "Psychiatric aspects of bariatric surgery". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 27 (5): 374–379. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000085. PMC 4162326. PMID 25036421.

- ^ a b Lin HY, Huang CK, Tai CM, Lin HY, Kao YH, Tsai CC, et al. (January 2013). "Psychiatric disorders of patients seeking obesity treatment". BMC Psychiatry. 13: 1. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-13-1. PMC 3543713. PMID 23281653.

- ^ a b c Marchese SH, Pandit AU (December 2022). "Psychosocial Aspects of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgeries and Endoscopic Therapies". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 51 (4): 785–798. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2022.07.005. PMID 36375996. S2CID 253486687.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Contival N, Menahem B, Gautier T, Le Roux Y, Alves A (February 2018). "Guiding the non-bariatric surgeon through complications of bariatric surgery". Journal of Visceral Surgery. 155 (1): 27–40. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2017.10.012. PMID 29277390.

- ^ O'Brien PE, Hindle A, Brennan L, Skinner S, Burton P, Smith A, et al. (January 2019). "Long-Term Outcomes After Bariatric Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Weight Loss at 10 or More Years for All Bariatric Procedures and a Single-Centre Review of 20-Year Outcomes After Adjustable Gastric Banding". Obesity Surgery. 29 (1): 3–14. doi:10.1007/s11695-018-3525-0. PMC 6320354. PMID 30293134.

- ^ a b c d e f Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, Kashyap SR, Schauer PR, Mingrone G, et al. (October 2013). "Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMJ. 347: f5934. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5934. PMC 3806364. PMID 24149519.

- ^ a b c d e f Wiggins T, Guidozzi N, Welbourn R, Ahmed AR, Markar SR (July 2020). "Association of bariatric surgery with all-cause mortality and incidence of obesity-related disease at a population level: A systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 17 (7): e1003206. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003206. PMC 7386646. PMID 32722673.

- ^ a b c d e Wiggins T, Guidozzi N, Welbourn R, Ahmed AR, Markar SR (July 2020). "Association of bariatric surgery with all-cause mortality and incidence of obesity-related disease at a population level: A systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 17 (7): e1003206. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003206. PMC 7386646. PMID 32722673.

- ^ a b Zhang R, Borisenko O, Telegina I, Hargreaves J, Ahmed AR, Sanchez Santos R, et al. (October 2016). "Systematic review of risk prediction models for diabetes after bariatric surgery". The British Journal of Surgery. 103 (11): 1420–1427. doi:10.1002/bjs.10255. hdl:10044/1/43870. PMID 27557164. S2CID 205508036.

- ^ a b c d e Baskota A, Li S, Dhakal N, Liu G, Tian H (2015-07-13). "Bariatric Surgery for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Patients with BMI <30 kg/m2: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0132335. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1032335B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132335. PMC 4500506. PMID 26167910.

- ^ a b c d e f Ribaric G, Buchwald JN, McGlennon TW (March 2014). "Diabetes and weight in comparative studies of bariatric surgery vs conventional medical therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Obesity Surgery. 24 (3): 437–455. doi:10.1007/s11695-013-1160-3. PMC 3916703. PMID 24374842.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Liao J, Yin Y, Zhong J, Chen Y, Chen Y, Wen Y, et al. (2022-10-28). "Bariatric surgery and health outcomes: An umbrella analysis". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 13: 1016613. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.1016613. PMC 9650489. PMID 36387921.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Colquitt JL, Pickett K, Loveman E, Frampton GK (August 2014). "Surgery for weight loss in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (8): CD003641. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003641.pub4. PMC 9028049. PMID 25105982.

- ^ Kominiarek MA, Jungheim ES, Hoeger KM, Rogers AM, Kahan S, Kim JJ (May 2017). "American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery position statement on the impact of obesity and obesity treatment on fertility and fertility therapy Endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Obesity Society". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 13 (5): 750–757. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.02.006. PMID 28416185.

- ^ a b Kwong W, Tomlinson G, Feig DS (June 2018). "Maternal and neonatal outcomes after bariatric surgery; a systematic review and meta-analysis: do the benefits outweigh the risks?". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 218 (6): 573–580. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.02.003. PMID 29454871. S2CID 3837276.

- ^ Morledge MD, Pories WJ (April 2020). "Mental Health in Bariatric Surgery: Selection, Access, and Outcomes". Obesity. 28 (4): 689–695. doi:10.1002/oby.22752. PMID 32202073. S2CID 214618061.

- ^ a b Kubik JF, Gill RS, Laffin M, Karmali S (2013). "The impact of bariatric surgery on psychological health". Journal of Obesity. 2013: 837989. doi:10.1155/2013/837989. PMC 3625597. PMID 23606952.

- ^ Beaulac J, Sandre D (May 2017). "Critical review of bariatric surgery, medically supervised diets, and behavioural interventions for weight management in adults". Perspectives in Public Health. 137 (3): 162–172. doi:10.1177/1757913916653425. PMID 27354536. S2CID 3853658.

- ^ Courcoulas A, Coley RY, Clark JM, McBride CL, Cirelli E, McTigue K, et al. (March 2020). "Interventions and Operations 5 Years After Bariatric Surgery in a Cohort From the US National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network Bariatric Study". JAMA Surgery. 155 (3): 194–204. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5470. PMC 6990709. PMID 31940024.

- ^ Małczak P, Pisarska M, Piotr M, Wysocki M, Budzyński A, Pędziwiatr M (January 2017). "Enhanced Recovery after Bariatric Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Obesity Surgery. 27 (1): 226–235. doi:10.1007/s11695-016-2438-z. PMC 5187372. PMID 27817086.

- ^ a b c d e f g "AGEB – AGEB Article". AGEB. Retrieved 2023-11-06.

- ^ Dai Y, Luo B, Li W (January 2023). "Incidence and risk factors for cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Lipids in Health and Disease. 22 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s12944-023-01774-7. PMC 9840335. PMID 36641461.

- ^ Laurenius A, Sundbom M, Ottosson J, Näslund E, Stenberg E (May 2023). "Incidence of Kidney Stones After Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery-Data from the Scandinavian Obesity Surgery Registry". Obesity Surgery. 33 (5): 1564–1570. doi:10.1007/s11695-023-06561-y. PMC 10156825. PMID 37000381.

- ^ Chen L, Chen Y, Yu X, Liang S, Guan Y, Yang J, et al. (July 2024). "Long-term prevalence of vitamin deficiencies after bariatric surgery: a meta-analysis". Langenbecks Arch Surg. 409 (1): 226. doi:10.1007/s00423-024-03422-9. PMID 39030449.

- ^ Ha J, Kwon Y, Kwon JW, Kim D, Park SH, Hwang J, et al. (July 2021). "Micronutrient status in bariatric surgery patients receiving postoperative supplementation per guidelines: Insights from a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies". Obes Rev. 22 (7): e13249. doi:10.1111/obr.13249. PMID 33938111.

- ^ a b Akhter Z, Rankin J, Ceulemans D, Ngongalah L, Ackroyd R, Devlieger R, et al. (August 2019). "Pregnancy after bariatric surgery and adverse perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis". PLOS Medicine. 16 (8): e1002866. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002866. PMC 6684044. PMID 31386658.

- ^ Panteliou E, Miras AD (April 2017). "What is the role of bariatric surgery in the management of obesity?". Climacteric. 20 (2): 97–102. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1262638. hdl:10044/1/48057. PMID 28051892. S2CID 24268282.

- ^ a b Knuth ND, Johannsen DL, Tamboli RA, Marks-Shulman PA, Huizenga R, Chen KY, et al. (December 2014). "Metabolic adaptation following massive weight loss is related to the degree of energy imbalance and changes in circulating leptin". Obesity. 22 (12): 2563–2569. doi:10.1002/oby.20900. PMC 4236233. PMID 25236175.

- ^ a b Cornejo-Pareja I, Clemente-Postigo M, Tinahones FJ (2019-09-19). "Metabolic and Endocrine Consequences of Bariatric Surgery". Frontiers in Endocrinology. 10: 626. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00626. PMC 6761298. PMID 31608009.

- ^ "Comparing the Benefits and Harms of Bariatric Procedures - Evidence Update for Clinicians". Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). 2021-07-15. Retrieved 2024-10-30.

- ^ a b c d Conner J, Nottingham JM (2023). "Biliopancreatic Diversion With Duodenal Switch". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 33085340. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ a b Ding L, Fan Y, Li H, Zhang Y, Qi D, Tang S, et al. (August 2020). "Comparative effectiveness of bariatric surgeries in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Obesity Reviews. 21 (8): e13030. doi:10.1111/obr.13030. PMC 7379237. PMID 32286011.

- ^ Brethauer SA, Schauer PR, Schirmer BD, eds. (2015-03-03). Minimally Invasive Bariatric Surgery. Springer. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-4939-1637-5.

- ^ a b Lee WJ, Almalki O (September 2017). "Recent advancements in bariatric/metabolic surgery". Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery. 1 (3): 171–179. doi:10.1002/ags3.12030. PMC 5881368. PMID 29863165.

- ^ a b van Wezenbeek MR, Smulders JF, de Zoete JP, Luyer MD, van Montfort G, Nienhuijs SW (August 2015). "Long-Term Results of Primary Vertical Banded Gastroplasty". Obesity Surgery. 25 (8): 1425–1430. doi:10.1007/s11695-014-1543-0. PMID 25519773. S2CID 23750600.

- ^ a b c Suarez DF, Gangemi A (January 2021). "How Bad Is "Bad"? A Cost Consideration and Review of Laparoscopic Gastric Plication Versus Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy". Obesity Surgery. 31 (1): 307–316. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-05018-w. PMID 33098054. S2CID 225049319.

- ^ a b c Meyer HH, Riauka R, Dambrauskas Z, Mickevicius A (March 2021). "The effect of surgical gastric plication on obesity and diabetes mellitus type 2: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Wideochirurgia I Inne Techniki Maloinwazyjne = Videosurgery and Other Miniinvasive Techniques. 16 (1): 10–18. doi:10.5114/wiitm.2020.97424. PMC 7991956. PMID 33786112.

- ^ a b Fernandes M, Atallah AN, Soares BG, Humberto S, Guimarães S, Matos D, et al. (January 2007). "Intragastric balloon for obesity". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (1): CD004931. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004931.pub2. PMC 9022666. PMID 17253531.

- ^ a b c Singh S, de Moura DT, Khan A, Bilal M, Chowdhry M, Ryan MB, et al. (August 2020). "Intragastric Balloon Versus Endoscopic Sleeve Gastroplasty for the Treatment of Obesity: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Obesity Surgery. 30 (8): 3010–3029. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04644-8. PMC 7720242. PMID 32399847.

- ^ a b Lal N, Livemore S, Dunne D, Khan I (2015). "Gastric Electrical Stimulation with the Enterra System: A Systematic Review". Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2015: 762972. doi:10.1155/2015/762972. PMC 4515290. PMID 26246804.

- ^ a b c d e f g Elrazek AE, Elbanna AE, Bilasy SE (November 2014). "Medical management of patients after bariatric surgery: Principles and guidelines". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 6 (11): 220–228. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v6.i11.220. PMC 4241489. PMID 25429323.

- ^ Toma T, Harling L, Athanasiou T, Darzi A, Ashrafian H (October 2018). "Does Body Contouring After Bariatric Weight Loss Enhance Quality of Life? A Systematic Review of QOL Studies". Obesity Surgery. 28 (10): 3333–3341. doi:10.1007/s11695-018-3323-8. PMC 6153583. PMID 30069862.

- ^ Cabbabe SW (2016). "Plastic Surgery after Massive Weight Loss". Missouri Medicine. 113 (3): 202–206. PMC 6140063. PMID 27443046.

- ^ Gilmartin J, Bath-Hextall F, Maclean J, Stanton W, Soldin M (November 2016). "Quality of life among adults following bariatric and body contouring surgery: a systematic review" (PDF). JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 14 (11): 240–270. doi:10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003182. PMID 27941519. S2CID 46824125.

- ^ a b c Moshiri M, Osman S, Robinson TJ, Khandelwal S, Bhargava P, Rohrmann CA (July 2013). "Evolution of bariatric surgery: a historical perspective". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 201 (1): W40–W48. doi:10.2214/AJR.12.10131. PMID 23789695.

- ^ a b c d Faria GR (2017). "A brief history of bariatric surgery". Porto Biomedical Journal. 2 (3): 90–92. doi:10.1016/j.pbj.2017.01.008. PMC 6806981. PMID 32258594.

- ^ Kurz CF, Rehm M, Holle R, Teuner C, Laxy M, Schwarzkopf L (November 2019). "The effect of bariatric surgery on health care costs: A synthetic control approach using Bayesian structural time series". Health Economics. 28 (11): 1293–1307. doi:10.1002/hec.3941. PMID 31489749. S2CID 201845178.

- ^ Tremmel M, Gerdtham UG, Nilsson PM, Saha S (April 2017). "Economic Burden of Obesity: A Systematic Literature Review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 14 (4): 435. doi:10.3390/ijerph14040435. PMC 5409636. PMID 28422077.

- ^ a b c d Liu D, Cheng Q, Suh HR, Magdy M, Loi K (December 2021). "Role of bariatric surgery in a COVID-19 era: a review of economic costs". Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 17 (12): 2091–2096. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2021.07.015. PMC 8310782. PMID 34417118.

- ^ Larsen AT, Højgaard B, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J (February 2018). "The Socio-economic Impact of Bariatric Surgery". Obesity Surgery. 28 (2): 338–348. doi:10.1007/s11695-017-2834-z. PMID 28735376. S2CID 2381246.

- ^ a b Hofmann B (April 2013). "Bariatric surgery for obese children and adolescents: a review of the moral challenges". BMC Medical Ethics. 14 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/1472-6939-14-18. PMC 3655839. PMID 23631445.

- ^ a b c d Jebeile H, Kelly AS, O'Malley G, Baur LA (May 2022). "Obesity in children and adolescents: epidemiology, causes, assessment, and management". The Lancet. Diabetes & Endocrinology. 10 (5): 351–365. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00047-X. PMC 9831747. PMID 35248172.

- ^ Armstrong SC, Bolling CF, Michalsky MP, Reichard KW (December 2019). "Pediatric Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery: Evidence, Barriers, and Best Practices". Pediatrics. 144 (6): e20193223. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3223. PMID 31656225. S2CID 204947687.

- ^ Martinelli V, Singh S, Politi P, Caccialanza R, Peri A, Pietrabissa A, et al. (January 2023). "Ethics of Bariatric Surgery in Adolescence and Its Implications for Clinical Practice". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 20 (2): 1232. doi:10.3390/ijerph20021232. PMC 9859476. PMID 36673981.

- ^ Torbahn G, Brauchmann J, Axon E, Clare K, Metzendorf MI, Wiegand S, et al. (September 2022). "Surgery for the treatment of obesity in children and adolescents". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (9): CD011740. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011740.pub2. PMC 9454261. PMID 36074911.

- ^ Thenappan A, Nadler E (April 2019). "Bariatric Surgery in Children: Indications, Types, and Outcomes". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 21 (6): 24. doi:10.1007/s11894-019-0691-8. PMID 31025124. S2CID 133605416.

- ^ Elkhoury D, Elkhoury C, Gorantla VR (April 2023). "Improving Access to Child and Adolescent Weight Loss Surgery: A Review of Updated National and International Practice Guidelines". Cureus. 15 (4): e38117. doi:10.7759/cureus.38117. PMC 10212726. PMID 37252536.

- ^ Hampl SE, Hassink SG, Skinner AC, Armstrong SC, Barlow SE, Bolling CF, et al. (February 2023). "Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Obesity". Pediatrics. 151 (2): e2022060640. doi:10.1542/peds.2022-060640. PMID 36622115. S2CID 255544218.

- ^ a b c Beamish AJ, Ryan Harper E, Järvholm K, Janson A, Olbers T (August 2023). "Long-term Outcomes Following Adolescent Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 108 (9): 2184–2192. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad155. PMC 10438888. PMID 36947630.

- ^ a b Wu Z, Gao Z, Qiao Y, Chen F, Guan B, Wu L, et al. (June 2023). "Long-Term Results of Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents with at Least 5 Years of Follow-up: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Obesity Surgery. 33 (6): 1730–1745. doi:10.1007/s11695-023-06593-4. PMID 37115416. S2CID 258375355.

External links

[edit] Media related to Bariatric surgery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bariatric surgery at Wikimedia Commons