Mughal dynasty

| House of Babur | |

|---|---|

| Imperial dynasty | |

| |

| Parent house | Timurid dynasty |

| Country | Mughal India |

| Place of origin | Timurid Empire |

| Founded | 21 April 1526 |

| Founder | Babur |

| Final ruler | Bahadur Shah II |

| Titles | List |

| Connected families | |

| Traditions |

|

| Dissolution | 1857 |

| Deposition | 21 September 1857 |

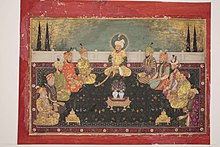

The Mughal dynasty (Persian: دودمان مغل, romanized: Dudmân-e Mughal) or the House of Babur (Persian: خاندانِ آلِ بابُر, romanized: Khāndān-e-Āl-e-Bābur), was a dynasty that ruled Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, and parts of China and Persia (Iran) as an amalgamate Mughal Empire from 1526 to 1857. They were the sovereign descendants of the Timurid Dynasty, a direct imperial branch of the Mongol emperor and conqueror Genghis Khan's bloodline. In the 1700s, the Mughal Empire was the wealthiest ruling empire in the world with the largest military on earth.[2]

The Mughal dynasty's founder, Emperor Babur (born 1483), was a direct patrilineal descendent of the Asian conqueror Timur (1336–1405) and matrilineal descendent of Genghis Khan (died 1227). His ancestors also maintained affiliations with the Genghishids and the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia through marriage and common ancestry traced back to conquests in the region.[3][4] During much of the Empire's history, the emperor functioned as the absolute head of state, head of government and head of the military while wealth and trade was often managed by the empress. During the dynasty's decline, much of the power shifted to the office of the Grand Vizier and the empire became divided into many regional kingdoms and princely states.[5] Although in the state of a steady but gradual dissolution, the Mughal dynasty continued to be the highest manifestation of sovereignty within the Indian subcontinent until the British occupation and deindustrialization of the region.

As one of history's most ethnically diverse kingdoms, all, the Muslim gentry, Maratha, Rajput, Sikh, and Persian leaders, held ceremonial acknowledgements under the Emperor and Empress as the sovereigns of South Asia.[6]

The British East India Company abolished both the dynasty and the empire on 21 September 1857 during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, and declared its own ascendancy as the ruling establishment of the subcontinent the following year. The last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II was convicted (r. 1837–1857) and exiled (1858) to Rangoon in the British-controlled Burma (present-day Myanmar), where he died without ever returning.[7]

Although the dynasty ended with Bahadur Shah II, direct descendants of the Imperial House of the Mughals still survive today.

Name

[edit]History and Lineages

[edit]The Mughal empire is conventionally said to have been founded in 1526 by Babur, a Timurid prince from Andijan which today is in Uzbekistan. After losing his ancestral domains in Central Asia, Babur first established himself in Kabul and ultimately moved towards the Indian subcontinent.[13] Mughal rule was interrupted for 16 years by the Sur Emperors during Humayun's reign.[14] It is also though by Russian linguist, Vladimir Braginskiĭ, That the Hikayat Aceh literature from Aceh Sultanate were influenced by Mughal dynasty historiography, as he found out the literal structure similarities of Hikayat Aceh with Mahfuzat-i-Timuri, as the former has shared the similar theme with the latter about the lifetime and exploits of the protagonist of Mahfuzat-i-Timuri, Timur.[15] Braginskiĭ also found the similarities in structure of both Hikayat Aceh and Mahfuzat-i-Timuri with Akbarnama manuscript.[15]

The Mughal imperial structure was founded by Akbar the Great around the 1580s, and it lasted until the 1740s shortly after the Battle of Karnal. During the reigns of Shah Jahan, Nur Jahan, and Aurangzeb, the dynasty reached its zenith in terms of geographical extent, economy, military, and cultural influence.[16]

The Mughals held approximately 24% share of world's economy and a military of one million soldiers.[17][18] At that time the Mughals ruled almost the entirety of South Asia with 160 million subjects, or 23% of the world's population.[19] The Dynasty's power rapidly dwindled during the 18th century with internal dynastic conflicts, incompatible monarchs, foreign invasions from the Persians and Afghans, as well as revolts from the Marathas, Sikh, Rajputs, and regional Nawabs (aristocrats).[20][21] By the time of the last Emperor, the dynasty's power was limited only to the Walled city of Delhi.

Many of the later Mughal princes had significant Indian Rajput and Persian ancestry through marriage, as emperors were born into the Rajput clan and often married Persian princesses.[22][23] Emperor Akbar the Great was half-Persian (his mother was of Persian origin), Jahangir was half-Rajput and quarter-Persian, and Shah Jahan was three-quarters Rajput.[24][25][26] Mughals played a great role in the flourishing of Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb (Indo-Islamic civilization).[27] Mughals were also great patrons of art, culture, literature and architecture. Mughal painting, architecture, culture, clothing, cuisine and Urdu language; all were flourished during Mughal era. Mughals were not only guardians of art and culture but they also took interest in these fields personally. Emperor Babur, Aurangzeb and Shah Alam II were great calligraphers,[28] Jahangir was a great painter,[29] Shah Jahan was a great architect[30] while Bahadur Shah II was a great poet of Urdu.[31]

Succession to the throne

[edit]

The Mughal dynasty operated under several basic premises: that the Emperor governed the empire's entire territory with complete sovereignty, that only one person at a time could be the Emperor, and that every male member of the dynasty was hypothetically eligible to become Emperor, even though an heir-apparent was appointed several times during an Emperor's term and Badshah Begum (Madame Emperor) Nur Jahan maintained distinct power as the sole female head and pioneer of the Mughal Renaissance, during whose reign the empire was at the highest point in its dynastic history.[1][2]

The certain processes through which imperial princes rose to the Peacock Throne, however, were very specific to the Mughal Empire. To go into greater detail about these processes, the history of succession between Emperors can be divided into two eras: Era of Imperial successions (1526–1713) and Era of Regent successions (1713–1857).

Disputed headship of dynasty

[edit]The Mughal Emperors practiced polygamy, and had several concubines in their harem, who produced children besides their wives. This makes it difficult to trace the direct lineages of each emperor.[32]

A man in India named Habeebuddin Tucy claims to be a descendant of the last mughal emperor Bahadur Shah II, but his claim is not universally believed.[33]

Another woman named Sultana Begum, who lives in the slums of Kolkata, claims that her late husband Mirza Mohammad Bedar Bakht was the great-grandson of Bahadur Shah II.[34]

A widely-accepted claim comes from Yaqoob Ziauddin Tucy, who is believed to be a sixth generation descendant of Bahadur Shah II. Living in Hyderabad, he has been campaigning to have the properties of the erstwhile Mughals returned by the government to legal heirs and demands the restoration of the Mughal scholarships that were discontinued a while back. Tucy also wishes that amount to be raised to ₹8,000, and that the government at least grant some economic relief to Mughal descendants left destitute after the British plunder of their wealth. Tucy has two sons,[35] and a younger brother, Yaqoob Shajeeuddin Tucy. Shajeeuddin Tucy serves the Indian Air Force, and has been a state guest to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, along with his two elder brothers. He frequently travels to various nations in the Middle East and central Asia, and also lives in Hyderabad along with his two sons Yaqoob Muzammiluddin Tucy and Yaqoob Mudassiruddin Tucy.[36]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (10 September 2002). Thackston, Wheeler M. (ed.). The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Modern Library. p. xlvi. ISBN 978-0-375-76137-9.

In India the dynasty always called itself Gurkani, after Temür's title Gurkân, the Persianized form of the Mongolian kürägän, 'son-in-law,' a title Temür assumed after his marriage to a Genghisid princess.

- ^ Lawrence E. Harrison, Peter L. Berger (2006). Developing cultures: case studies. Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 9780415952798.

- ^ Berndl, Klaus (2005). National Geographic Visual History of the World. National Geographic Society. pp. 318–320. ISBN 978-0-7922-3695-5.

- ^ Dodgson, Marshall G.S. (2009). The Venture of Islam. Vol. 3: The Gunpowder Empires and Modern Times. University of Chicago Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-226-34688-5.

- ^ Sharma, S. R. (1999). Mughal Empire in India: A Systematic Study Including Source Material. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-817-8.

- ^ Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2004). Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-203-71253-5.

- ^ Bhatia, H.S. Justice System and Mutinies in British India. p. 204.

- ^ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (2002). Thackston, Wheeler M. (ed.). The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Modern Library. p. xlvi. ISBN 978-0-375-76137-9.

In India the dynasty always called itself Gurkani, after Temür's title Gurkân, the Persianized form of the Mongolian kürägän, 'son-in-law,' a title he assumed after his marriage to a Genghisid princess.

- ^ John Walbridge. God and Logic in Islam: The Caliphate of Reason. p. 165.

Persianate Mogul Empire.

- ^ a b c Hodgson, Marshall G. S. (2009). The Venture of Islam. Vol. 3. University of Chicago Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-226-34688-5.

- ^ Canfield, Robert L. (2002). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-52291-5.

- ^ Huskin, Frans Husken; Dick van der Meij (2004). Reading Asia: New Research in Asian Studies. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-136-84377-8.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham (2007), Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Moghuls, Penguin Books Limited, ISBN 978-93-5118-093-7

- ^ Kissling, H. J.; N. Barbour; Bertold Spuler; J. S. Trimingham; F. R. C. Bagley; H. Braun; H. Hartel (1997). The Last Great Muslim Empires. BRILL. pp. 262–263. ISBN 90-04-02104-3. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ a b V.I. Braginsky (2005). The Heritage of Traditional Malay Literature: A Historical Survey of Genres, Writings and Literary Views. BRILL. p. 381. ISBN 978-90-04-48987-5. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

...author shares T. Iskandar's opinion that Hikayat Aceh was influenced by Mughal historiography..

- ^ "BBC - Religions - Islam: Mughal Empire (1500s, 1600s)". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (25 September 2003). Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical Statistics: Historical Statistics. OECD Publishing. pp. 256–. ISBN 978-92-64-10414-3.

- ^ Art of Mughal Warfare." Art of Mughal Warfare. Indiannetzone, 25 August 2005.

- ^ József Böröcz (10 September 2009). The European Union and Global Social Change. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 9781135255800. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Hallissey, Robert C. (1977). The Rajput Rebellion Against Aurangzeb. University of Missouri Press. pp. ix, x, 84. ISBN 978-0-8262-0222-2.

- ^ Claude Markovits (2004) [First published 1994 as Histoire de l'Inde Moderne]. A History of Modern India, 1480–1950. Anthem Press. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-1-84331-004-4.

- ^ Jeroen Duindam (2015), Dynasties: A Global History of Power, 1300–1800, page 105 Archived 6 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Mohammada, Malika (1 January 2007). The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India. Akkar Books. p. 300. ISBN 978-8-189-83318-3.

- ^ Dirk Collier (2016). The Great Mughals and their India. Hay House. p. 15. ISBN 9789384544980.

- ^ Duindam, Jeroen (2016). Dynasties: A Global History of Power, 1300–1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-06068-5.

- ^ Mohammada, Malika (2007). The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India. Aakar Books. ISBN 978-81-89833-18-3.

- ^ Alvi, Sajida Sultana (2 August 2012). Perspectives on Indo-Islamic Civilization in Mughal India: Historiography, Religion and Politics, Sufism and Islamic Renewal. OUP Pakistan. ISBN 978-0-19-547643-9.

- ^ Taher, Mohamed (1994). Librarianship and Library Science in India: An Outline of Historical Perspectives. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7022-524-9.

- ^ Dimand, Maurice S. (1944). "The Emperor Jahangir, Connoisseur of Paintings". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 2 (6): 196–200. doi:10.2307/3257119. ISSN 0026-1521. JSTOR 3257119.

- ^ Asher 2003, p. 169

- ^ Bilal, Maaz Bin (9 November 2018). "Not just the last Mughal: Three ghazals by Bahadur Shah Zafar, the poet king". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Dalrymple, William (2006). The Last Mughal. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4088-0092-8.

- ^ Rao, Ch Sushil (18 August 2019). "Who is Prince Habeebuddin Tucy?". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Destitute Mughal empire 'heir' demands India 'return' Red Fort". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ Baseerat, Bushra (27 April 2010). "Royal descendant struggles for survival". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ^ "Monumental issue Uae – Gulf News". 6 June 2024. Archived from the original on 6 June 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Asher, Catherine Ella Blanshard (2003) [First published 1992]. Architecture of Mughal India. The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. I:4. Cambridge University Press. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1.